One Night In Montreal

Tomorrow marks the tenth anniversary of a most extraordinary fight night and a shocking knockout victory. So let’s look back to when our own Rafael Garcia ventured into the Montreal night to cover what appeared to be, at least on paper, a fascinating and highly competitive title match in the light heavyweight division, but instead proved a brief but electrifying encounter. Check it out:

Despite the crappy weather on this particular night, Montreal is full of action throughout the weekend. The Grand Prix circus has rolled into town, taking over the city’s downtown district and packing bars, restaurants and hotels with throngs of racing enthusiasts. However, Ile Ste-Helene is the true racing capital for the event. Located a quick metro ride underneath the Saint Lawrence river and just south of Montreal proper, the islet hosts practice and qualifying races for two days before the main event takes place on Sunday.

None of this bears much of an effect on the Plateau, a bohemian neighborhood populated by well-to-do families, with a smattering of students and artists. The Plateau also happens to be where I live, and when I jump on the metro to head to the Bell Centre, I’m only reminded of all the activity going on when I get to the Berri-UQAM metro station. This is where the yellow line that takes Grand Prix fanatics to Ile Ste-Helene deposits them on the way back from their day at the races. At Berri-UQAM, squadrons of men, between 25 and 55, decked out in jackets and sports shoes overburdened with Ferrari and Puma logos, ride the escalators and then rush to board the metro car I’m riding in. Most of them head downtown to keep the fun going; others stop at the Old Port to get a drink and a steak; and a good chunk of them descend with me at the Bonaventure station, down the escalators and into the entrails of the Bell Centre.

Upon my arrival at the arena’s media center, the first thing I see is Chad Dawson’s promoter Gary Shaw leaning on a desk looking cranky. He’s arguing with the old, portly gentleman who controls access to the innards of the building. In a thickly accented English, the Bell Centre official demands from Shaw: “Monsieur, I need to see your bracelet before you go in.” Shaw’s reaction is to raise his left arm and uncover a huge, silvery watch as he firmly replies, “It’s worth five thousand, what else do you want?” The Bell Centre employee issues his comeback impassively and unimpressed: “I need you to put on one of our bracelets before I let you in.” A young, female assistant jumps in. “Here monsieur, you can wear this one,” she says, while handing him a green, all-access bracelet. “Can I put it on your wrist?” she asks. “Honey, you’re so cute you can put it anywhere you want,” says Shaw.

Before I finally find my spot in the press gallery, I get to see way more of the inner recesses of the Bell Centre than I ever thought possible. As I haphazardly make my way through various tunnels and staircases, the most interesting scene I encounter, by far, is the one at the improvised backstage lobby where the ring-card girls and dancers (that’s right, Montreal boxing shows have sexy go-go dancers) hang out. Here the ladies get a chance to relax between appearances, have a drink and spruce themselves up before heading back out to do their thing. The view is superb, with plenty of skin, sexy high-heels, plunging necklines and short skirts surrounding me, and I would gladly miss the whole damn boxing show if it meant I could stay here handing out towels and assisting with the glitter mascara, but it’s not meant to be. The girls’ smiles were as enigmatic, and their bodies as sensual, as getting brusquely kicked out by the massive security guard was humbling.

So I leave the lobby of beauty and walk down a hallway leading to the floor of the Bell Centre. Before I know it, I bump into another body-builder dressed in black guarding a gleaming white Lamborghini that is so heart-breakingly beautiful it almost makes me tear up. Despite his intimidating appearance, this security guy turns out to be really charming. He patiently explains to me that my red bracelet does not give me access to the floor, and I have to climb up, way up, above the nosebleeds, to reach the press gallery where I’ll have the chance to perch myself atop a tall chair and survey the whole scene.

When I finally reach the summit, a couple dozen scribes already occupy the seats around mine. Most focus on the large screens above the ring that broadcast the preliminary fights with crisp clarity. Some gaze at the individual screens placed directly in front and above each pair of seats while a handful let their eyes wander to the live action below. As soon as I seat myself it’s clear the media have been relegated to this lofty spot to maximize revenue. Looking down, there’s no press-row near the ring, only seats for ticket-holders with some spots for photographers and camera crews. The ringside seats sell for six hundred; the nosebleeds for sixty.

By the time local favourite and middleweight knockout artist David Lemieux climbs in the ring, half the seats made available to the public are occupied. Lemieux receives huge cheers from the audience just for showing up, and his contest against the 31-year old 11-1 Robert Swierzbinski from Poland is a nasty, brutish and short affair. Lemieux knocks him down three times — first with a body shot, then with a violent left hook and then with an even more violent left hook — before the referee halts the massacre. I only saw Lemieux get hit once, with a left hook that annoyed him no more than a remora annoys a shark.

As much of a mismatch as this fight was, Lemieux’s punching power doesn’t cease to amaze. After getting up from the second knockdown, the Pole already had the look of someone who has suddenly understood the meaning of “cannon fodder”. And after the third knockdown, I had to hold on to my chair as the French-Canadian journalist to my right hollered like a banshee. But even if the crowd loved the knockout, it’s clear this fight does next to nothing for the Montrealer’s career. Will his handlers ever again put him in a risky fight, or will they continue to milk him by matching him against nobodies?

No other tilts of consequence took place before the bout between Yuriorkis Gamboa and Darleys Perez, which opened HBO’s broadcast. Kevin Bizier had been scratched from the card a couple of weeks before and now the word in the press room was that the scheduled Eleider “Storm” Alvarez vs Allan Green bout had been cancelled by HBO for reasons unknown, some last minute thing, no doubt.

The crowd cheers loudly when Gamboa appears on the big screen as he’s about to begin his ring-walk (Perez’s own ringwalk was not televised), duly escorted by his promoter 50 cent, but it’s unclear whether the ticket-holders are reacting to the boxer or to the rapper/impresario. When Michael Buffer begins his spiel the Bell Centre roars, and when the name of Montreal is mentioned, the response is deafening.

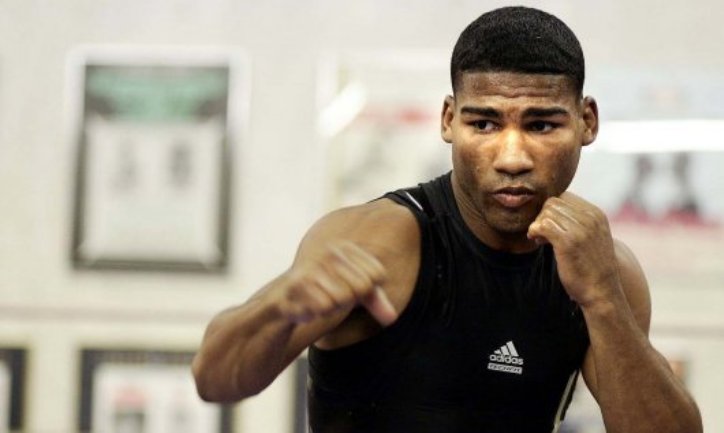

Gamboa scores a knockdown in the first round with a quick left hook followed by a right hand that doesn’t quite land but helps the Colombian on his journey to the canvas. Perez gets up quickly and it seems as if his going down is more a result of the Cuban’s hand-speed than of his power. At 135 pounds, Yuriorkis looks ripped; he wasted none of the nine pounds he now has to work with since moving up from featherweight. In his first fight in more than six months, he’s also his usual cocky and confident self. When the bell rings to signal the end of a round, he walks back to his corner with his arms hanging down arced by his sides, a small and lean version of Mike Tyson with the intense stare to match.

By the fifth, Perez is feeling Gamboa’s power. His face is marked up and, despite his bravado, he’s getting tagged more and more often. Gamboa is firmly in control of the action, comfortable in the knowledge that there’s pretty much nothing the Colombian can do to hurt him. “El Ciclon de Guantanamo” is so comfortable that he starts doing that move where he lands a punch, then backs away while turning his head in a different direction from where his opponent stands, before darting back to land a quick one-two. The talent mismatch, however, soon enough becomes tedious, as Gamboa doesn’t commit to his attack, relying too much on lateral movement and doing too little punching. The crowd begins to jeer and howl during the middle rounds, but this has little effect on the fighters’ performances; the sixth is as boring as the seventh is hollow. It’s hard to believe Alvarez vs Green would’ve been worse than this.

There’s something obnoxious about a boxer who can end a fight any time he wants to, but simply refuses to let his hands go. After all, nobody likes a tease. The final bell rings to wake me from my stupor and I realize I forgot to score the fight. Relief comes from the fact there’s no reason anyone not in need of a guide dog should give Perez more than a few rounds; nonetheless, two judges give him four and one gives him five.

What a few minutes ago was a bitterly comatose crowd roars when Michael Buffer introduces Adonis “Superman” Stevenson before the main event. This is it, the big fight everyone’s been waiting for. Another adopted Montrealer (“Superman” was born in Haiti) gets his chance at the big time in his first world championship bout. Buffer’s introduction of the champion, Chad Dawson, draws boos that are equally loud, and everyone is more than ready to rumble before the master of ceremonies commands them to be.

As Buffer wraps up his bit and the fighters head back to their corners after receiving the ref’s instructions, just moments from the opening bell, the crowd suddenly breaks out the uncharacteristic-for-boxing Ole! Ole! Ole! chant usually sung at European soccer games. The moment is as fleeting as it is rousing, and more than welcome and warm in a night that hasn’t offered a whole lot of action inside the ropes. The fact that everyone joins in reminds the audience of the reason they all came to the Bell Centre in the first place. The chant unites the thousands of Montrealers in firm support of their hero, the 35-year-old underdog with the fearsome left-cross, Adonis Stevenson.

During the first few seconds of the fight I quickly sketch a grid on a sheet of paper to assist me in keeping score this time. I adjust my seat and lean far out over the edge of my desk to make sure I can see the action live and in the flesh as opposed to the slightly delayed TV broadcast. But as soon as I finish these little adjustments and begin to process the action happening inside the ring, all hell breaks loose.

It happened in a flash, yet my mind registered everything. I saw Stevenson throw a measuring jab followed by a stiff left hand. I saw Dawson ever so lightly move his head away from the trajectory of Stevenson’s punch while he initiated a motion to throw a shot of his own. I saw Stevenson’s left connect just below Dawson’s right ear. I saw a blonde lady seating ringside jump out of her seat to a fully standing position while throwing both arms in the air as Dawson’s body was only midway on its downward trajectory. I saw the full extent of Dawson’s six-feet-one-inch frame laying on his back on the bright red canvas. And in a flash, in a scenario better than that ever envisioned by Stevenson and the thousands of fellow Montrealers on site, it was all over.

Such a brief outing does little to dispel any doubts regarding Stevenson’s talent, but it will only enhance his reputation as a genuine power puncher. His following in Quebec will at least double in both enthusiasm and numbers, and big names will soon come knocking hat in hand for a chance to face him in his own backyard. But while his future looks brighter than ever, there’s little reason to think any of this was going through Stevenson’s head as he bellowed with joy and fell to his knees moments after scoring the biggest win of his life.

Montreal has once again staged a memorable boxing event. The redeeming moment of what had been an underwhelming night of boxing was a shocking upset and a conclusive knockout which will be preserved proudly and deservedly in the history books as well as in the minds of those present that night. Here’s to many more such nights in Montreal. Here’s to many more such moments for boxing. Here’s to Adonis “Superman” Stevenson. — Rafael Garcia