July 9, 1989: Rosario vs Jones

When we compare and rank boxers of the past, something all serious fight fans love to do, one of the key criteria is longevity. This has less to do with the span of time between a pugilist’s first contest and their last, and more with how long they were able to compete at the elite level. History’s greatest boxers have lengthy primes and defeated top contenders and champions well into the second decade of their careers. And some, such as Sam Langford, Sugar Ray Robinson, George Foreman, Bernard Hopkins and Archie Moore, astonished everyone with their ability to ignore the calendar and keep scoring big wins more than two decades after their pro careers began.

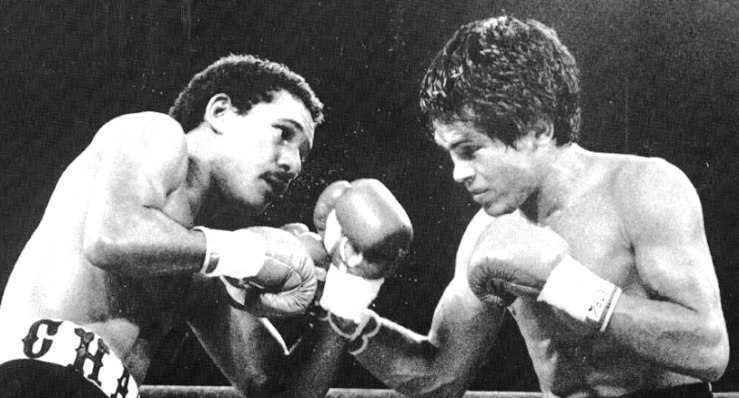

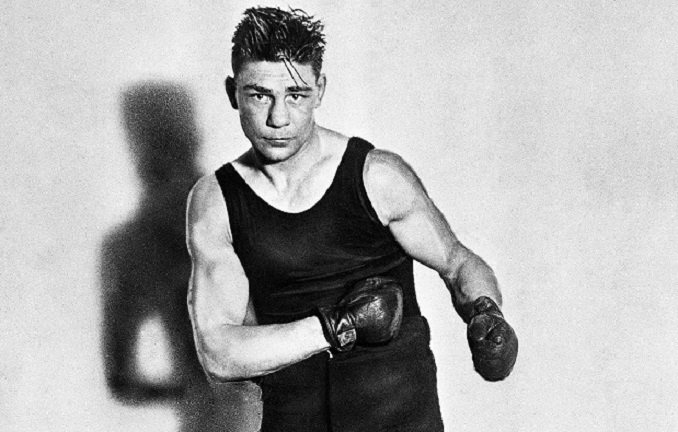

But then there are the champions who appear to have all the natural talent and skill but, for whatever reason, just can’t last. When Edwin Rosario emerged in the early 80’s, many were impressed with the young Puerto Rican’s blend of smooth boxing skills and devastating power. Having turned pro days before he turned sixteen, “Chapo” was a top contender in the lightweight division before he was twenty, with the poise and fighting instincts of someone much older. All agreed he was a sure-fire future world champ and there was talk of matching him with lightweight king Alexis Arguello, but then the Nicaraguan legend moved up to 140 to challenge Aaron Pryor. So instead Rosario took on Jose Luis Ramirez for the vacant WBC title.

And already one could see the cracks in Rosario’s game. Ramirez was one tough Mexican warrior and he subjected the younger fighter to pressure and pain the likes of which Edwin had never encountered before. While he out-boxed Ramirez in the first half of the match, he found himself fighting for his life in the late stages and won the title by the narrowest of margins on the scorecards. Further slippage in Rosario’s technique was evident just a year later when he barely outpointed Howard Davis Jr., and six months after that he suffered defeat for the first time when he was stopped in a short but very violent battle with Ramirez that was 1984’s Fight Of The Year.

“Chapo” rebounded in 1985 with four wins, including a decision over Frankie Randall, and was rewarded with a title shot against Hector “Macho” Camacho. In an exciting and somewhat controversial battle at Madison Square Garden, Rosario almost handed Camacho his first loss, rocking him repeatedly before dropping a close decision to his fellow Puerto Rican. Interestingly, the two were separated by less than a year in age, but Camacho was viewed as the young star with enormous potential while Rosario already had the air of a battle-worn veteran. But Edwin was still dangerous and three months later the WBA lightweight champion, Livingston Bramble, learned that the hard way when he failed to respect Rosario’s power and was knocked out in the second round.

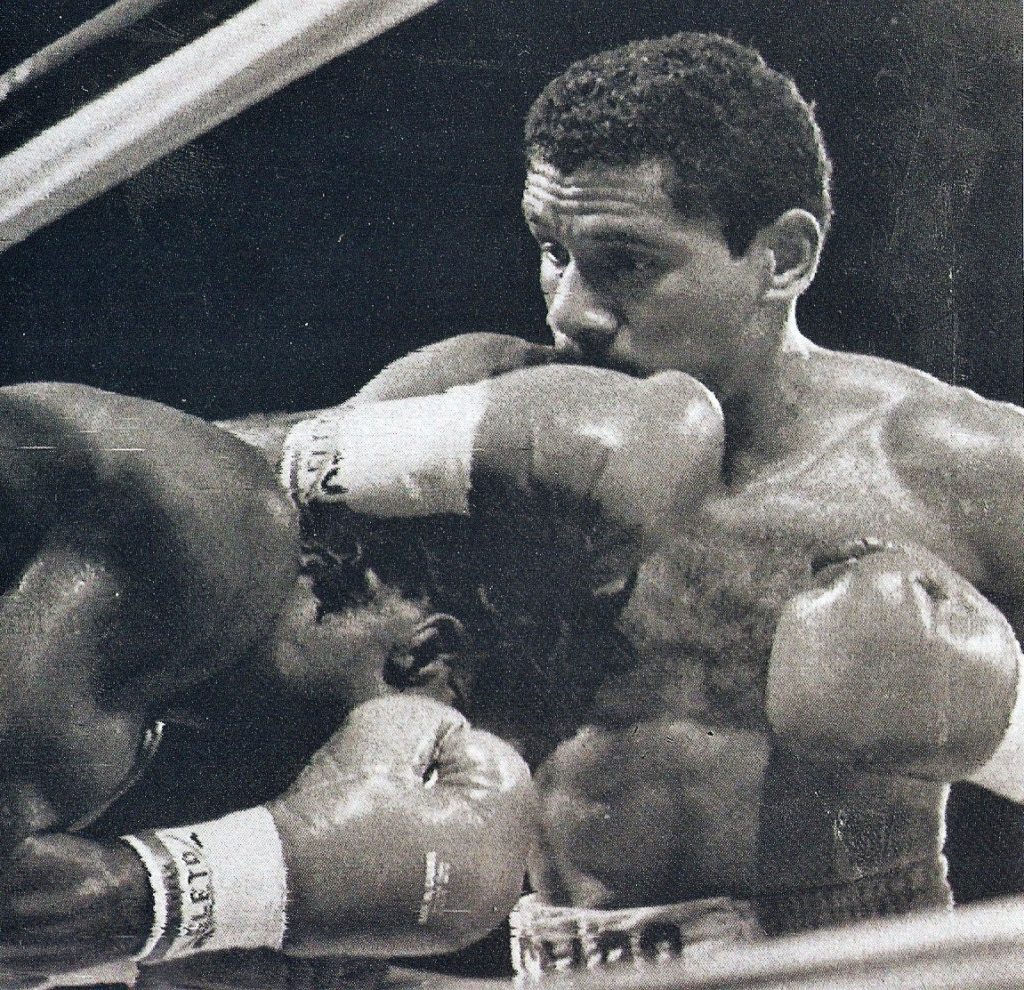

The roller-coaster ride that was the career of Edwin Rosario continued as he twice successfully defended his new title before Julio Cesar Chavez handed him a one-sided battering that was prolonged, vicious and painful. Chavez was moving up in weight to challenge Rosario but it was the Mexican who was stronger, his powerful body punches and relentless attack grinding Edwin down until the champion’s trainer had no choice but to finally halt the massacre in round eleven.

“Rosario never quit,” said HBO’s Larry Merchant at ringside, “but his corner did the right thing.”

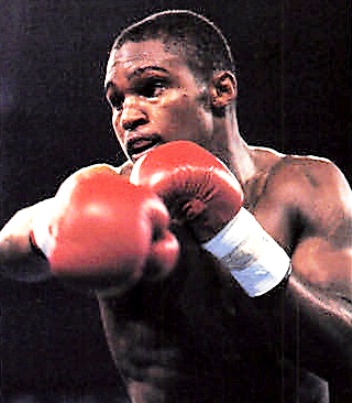

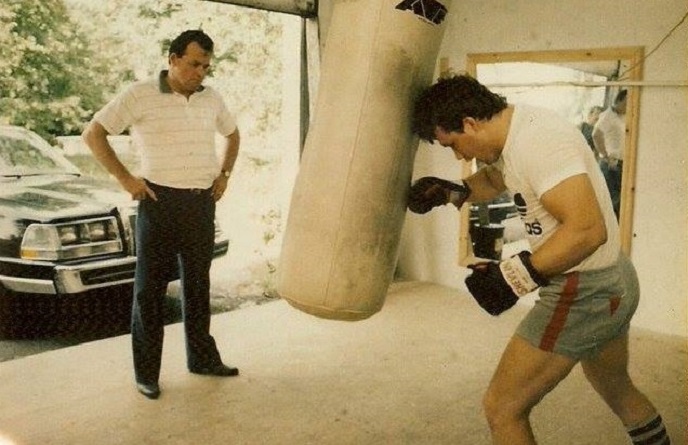

Despite the fact that he was only 24-years-old, the Chavez defeat marked the end of Rosario’s prime and evidently his management team understood this as the combined records of his next six opponents was 40-62-1. But those six wins impressed the WBA enough to have Rosario compete against southpaw Anthony “Baby” Jones, who boasted a 20-1-1 record, for their vacant world title after Chavez moved up to 140. Jones, a Detroit native and member of the famous Kronk stable, was trained by Emanuel Steward, but he came into the match a 4-to-1 underdog. So imagine the surprise of many at ringside when it was “Baby” who set the pace and got the better of the action.

Admittedly, it didn’t look that way in the opening round when Rosario started fast and cracked Jones with some sharp right hands. But after a stern lecture in his corner from Steward, Jones stood his ground and started pressing, backing up Rosario and outworking the former champion.

“I thought Jones came out to box,” said Rosario later, “but he came to fight.”

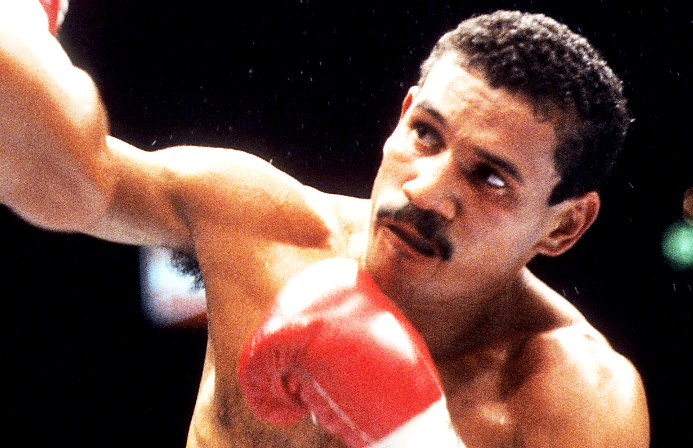

Near the end of round three Jones buckled “Chapo’s” legs with a flush left to the chin and he out-slugged Rosario in rounds four and five, landing heavy shots to the older man’s body. Meanwhile Rosario’s blows appeared to lack snap and failed to affect Jones. Or at least that was the case until near the mid-way point of round six when Rosario came over the top with a perfectly timed right hand that detonated on “Baby’s” chin. Jones crashed to the canvas so hard he bounced, before he somehow beat the count. But he was out on his feet; three punches later the referee moved in and caught Jones as he fell and the fight was stopped. Rosario had won his third world title.

“I was weaving down and Jones was weaving up,” said Rosario. “And pop! Finish!”

“He’s gone, he’s shot,” said Emanuel Steward. But the trainer was talking about the new champion, not Andrew Jones.

And it was true. Just 26, Edwin Rosario’s ability to compete at the highest level was a shaky proposition at best. A few years before, he was a complete fighter, one of the best in the game, but the reflexes had eroded and the skills had faded.

“He knows he’s over the hill,” confided his translator to Steve Farhood before the Jones fight. “He has four kids. When he wakes up in the morning, he’s a father. Chavez, Pernell Whitaker, they love boxing. Edwin is sick of it.”

Maybe so, but the roller-coaster ride continued a while longer. In his next fight, “Chapo” lost his title to Juan Nazario, but the year after that he was a champion yet again, defeating Loreto Garza for the super lightweight crown. He hungered for a rematch with Chavez but it never happened. Instead he suffered defeats to Akinobu Hiranaka and Frankie Randall and then he started taking losses outside the ring, to drugs and alcohol. His marriage fell apart and soon the money was gone and after four years away from boxing he launched a comeback, hoping for a big payday with Oscar De La Hoya.

Edwin Rosario never lost his vaunted punching power and his final fight was a second round knockout win in September of 1997. Three months later, after a visit with his children, he said he felt tired and needed a rest. He went to bed and never woke up, suffering an aneurysm and dying in his sleep. The doctors later said that Rosario’s history of alcohol and drug abuse was a factor in his untimely demise.

— Robert Portis

The sobriquet given to him in Puerto Rico as “the next Gómez” and the injustice he suffered in his 1985 fight against Macho Camacho disheartened Rosario. These two factors together with the drugs and the alcohol did him in. Nonetheless we Puerto Ricans fondly relish his memory as a great but emotionally flawed warrior.

El mejor pegador del peso ligero junto con mano de piedra Duran ….Edwin el chapo Rosario pegaba como patada de mula y Julio Cesar Chaves le preguntaron quien fue el boxeador que mas duro le pego y dijo Chapo Rosario orgullo del barrio candelario en Toa Baja Puerto Rico.