Hardy vs Vincent: ‘A Sellable Thing’

With Katie Taylor vs Amanda Serrano set for April 30th at Madison Square Garden and already attracting major-league excitement and anticipation, it seems like a good time to look back a few years and recollect one of the events that helped pave the way for the continued growth of female professional boxing. Here is Blake Cass’ in-depth recollection of the fight within the fight, that being the struggle for Heather Hardy and Shelly Vincent to receive the respect and compensation they deserved after their first battle in 2016 drew thousands of ticket-buyers to Coney Island. Check it out:

Dressed in black spandex and sporting her long blond hair in pig tails, Heather Hardy stepped into the ring at the BB King Club and Grill in mid-town Manhattan to face Shelly Vincent for the first time. It was January 27, 2016. Vincent had just fought and defeated Renata Desmodi; four months earlier, Hardy had beaten Desmodi herself. Now the stage was set, which was why Lou DiBella, promoter of both Hardy and Vincent, had asked Heather to attend the fight. DiBella wanted both boxers in the ring to help build up the rivalry.

“I’m not really in the business of going after people,” says Hardy. “This was something that Lou asked me to do because it’s what was best for women’s boxing. Like he gets girls on TV and it’s going to open doors for everyone. So, okay, but I try to preserve as much of myself as I can. Going up there and not being an asshole, but giving the fans what they want to see. Because it was all her fans in attendance. I never would have been cool with it if it were at one of my fights with my fans.”

And so here she was, standing face-to-face with Shelly Vincent in front of a jeering crowd, trying to preserve as much of herself as possible. Hardy faced down the fans with a smile and said something, but her words were lost to the overwhelming noise.

“She’s been avoiding me for three years,” Vincent claimed. “I’m going to put you to sleep. It’s hot in New York when Shellito come that way.”

Hardy turned to face Vincent. “You gonna slap me to sleep?” she said over all the yelling and noise. Then, possibly because she knew she had to up the theatrics, she leaned in and said again, “You gonna slap me to sleep?”

“I’m not even gonna go to the head,” Vincent told her. “I’m going to put you out with body shots.”

“I look forward to it,” said Hardy.

Hardy had just celebrated her birthday and Vincent had come prepared with a gimmick fit for the occasion. After handing over an envelope with a birthday card, Vincent stooped down because she dropped something—a match. When she stood back up, she handed it to Hardy. “To light the card on fire and ignite some heat,” she said and smiled broadly.

Hardy, whose boxing nickname is “The Heat,” seemed amused by the prank. As she read the card aloud to the audience, a beaming, self-pleased Vincent shifted her weight from one leg to the other. Some people may find Vincent’s looks—tattoos over both arms, her torso and neck—and her aggressive behavior off-putting but in this moment it was easy to see why she has been able to cultivate such a dedicated group of followers, many of them children who look up to her as a role model. The demands of adulthood can erase spontaneity and playfulness in people, but Vincent manages to retain these qualities of childhood, an astonishing fact when one considers what she endured growing up: physical abuse from her stepfather and, when only 13, rape by one of her mother’s boyfriends.

Standing behind Vincent was a man with square-framed glasses with a tan zip-down sweater and a matching newsboy hat turned backward. An unknowing spectator might have confused him for someone who had accidentally entered the establishment thinking he was there to hear some live blues or jazz or maybe recite some of his poetry at the open mic. The cool cat in tan was Lou DiBella, one of the great anomalies in the world of boxing promotion. He lingered off to the side, observing the spectacle, until the announcer turned to him: “This seems like a match any promoter would love to make. Are we going to see it?”

“Yes,” DiBella promised. “And you’re going to see it soon.”

Women’s boxing had received a slight boost due to the inclusion of the sport in the 2012 Olympic games. Golden Boy Promotions and Top Rank have since signed a long-term contract with two Olympians, Marlen Esparza and Mikaela Mayer, respectively. Now these companies can say they have a vested interest in women’s boxing at a time when there is greater scrutiny of gender and income inequality. Boxes checked.

But Lou DiBella had been promoting female boxers long before it became at all trendy. His female fighters include Hardy, Vincent, Jennifer Salinas, Amanda Serrano, and Cindy Serrano. And he promoted Heather Hardy’s pro debut back in 2012. “It was World War II,” DiBella recalls. “Heather bled, she was in trouble, and the other girl was a little warrior.” As DiBella tells it, 50 Cent was there and he turned to the promoter before the battle was over to say, “Bro, this is the best fucking fight of the whole show.”

DiBella promotes these women out of respect for them as athletes. “Because believe me,” he says, “I haven’t made any money promoting them.” And while he hustled behind the scenes, trying to secure a televised fight date for the Hardy vs Vincent fight, he kept both women active. Hardy fought Anna Donatella Hultin in April and then Kirstie Simmons in June. Vincent defeated Elizabeth Anderson in April and then Christina Ruiz in July of 2016, and it was right after the Ruiz fight that DiBella delivered what he thought was great news for Vincent.

“We’ve got the fight with Heather,” Shelly recalls DiBella telling her as she left the ring at Foxwoods after defeating Ruiz for the second time. She had faced Ruiz the previous year, a fight she won by unanimous decision but this time she had gotten a hard-earned split decision win and as she stepped through the ropes, anyone could see that she was totally exhausted. “Do you want to take it?” DiBella asked.

Vincent had been calling Hardy out since Heather’s third pro fight and had even gone so far as to attend several of Hardy’s bouts so she could antagonize her potential opponent. When she wasn’t able to approach Hardy in person, Vincent resorted to accosting her on social media. The funniest of these posts—funny because it is perhaps the oddest and least menacing—was an Instagram post of a feather-plucked turkey attached to a photoshopped image of Hardy’s head. It wasn’t a stretch to say that Heather Hardy had been on the forefront of Vincent’s mind for the past three years, which made her response even more surprising. Shelly Vincent, the tattooed, five-foot tall punching dynamo with a mouth as toxic as a drop of mercury, froze. Possibly for the first time in her public life, she couldn’t think of anything to say.

“You can’t say no,” she recalls DiBella telling her. “We got it on television. It’s a go. You gotta do it.”

“What?” Vincent said, feeling overwhelmed.

Vincent’s head hadn’t been in the fight with Ruiz. It wasn’t a good time in her life. All through her training camp, she had been preparing for her rape case to finally go to trial. And now that the fight with Ruiz was behind her, she was looking forward to a trip she had planned with her girlfriend, the boxer Jennifer Salinas. Salinas had also been abused when she was a child, and they were going to Bolivia to take part in a counseling program for rape survivors. The fight with Hardy was slated for August 22nd, just one month away. Vincent knew that if she accepted the offer, it would mean having to cancel her Bolivia trip. But after a brief hesitation she took the fight. After all, she knew she would never get this opportunity again, an opportunity she had practically created on her own, out of a stubborn refusal to accept the career inertia that so many female boxers face.

When she first started calling Hardy out, Vincent was still signed to CES, a regional boxing promoter and Hardy was signed with DiBella Entertainment. While promoters do sometimes work together, it doesn’t happen unless they have a very good relationship or if there is a lot of money to be made—more money than they could make by themselves. “So there was like no physical way that we could actually fight,” Hardy says. “It was really just theatrics…. She was piggybacking on me and my media attention.”

Heather Hardy is, as much as a female boxer can be in this country, a media darling. And she didn’t need a fight with Vincent to advance her career. She was popular, had a huge social media following, and could bring action to the box office, personally selling thousands of dollars in ticket sales before a fight. But Vincent did need the fight, at least from a career perspective. She would benefit from the media exposure that a clash with Hardy would generate, just as she had benefited from her antics at Hardy’s boxing events.

There were other reasons Vincent wanted to fight Hardy—Vincent will go on at length on this subject to anyone who asks—but that’s not so important as one simple fact: had Vincent not pursued Hardy so tenaciously, it’s unimaginable that this fight would have ever happened. Hardy admitted as much when discussing an altercation that the two had at the Roseland Ballroom.

“Lou wound up breaking us up, and I think that’s when he saw an opportunity there. Like there were issues, controversy, and shortly thereafter he signed her. She was still doing fights up in Rhode Island, but when Lou finally signed her, it created the build up to when are we going to make it happen. We wanted to make this a big show for TV. Because it was a sellable thing.”

DiBella was able to secure a place for Hardy vs Vincent on the undercard of the Errol Spence Jr. vs Leonard Bundu match at the Ford Amphitheater in Coney Island, an event being televised by Premier Boxing Champions on NBC. “I busted my balls to make it happen,” DiBella says. “And then Al Haymon, who a lot of people want to sit there and hate, let me get a TV slot for it.”

Both Hardy and Vincent had fought in venues with greater seating capacity than the Ford Amphitheater, an outside venue that can accommodate five thousand, but neither had performed on national TV. Hardy may not have needed Vincent, but it was “Shelito’s Way,” through sheer tenacity, who had made this opportunity possible. And there was more on the line for Vincent than simply beating a fighter she had been calling out for years.

Shelly Vincent began boxing late in her teens, as a kind of therapy for all that she had endured as a girl. As is the case with so many other fighters, boxing saved her life.

“I did cocaine, I sniffed heroin, just everything, tried to overdose on ecstasy pills. I was trying to kill myself. I had guns to my head and I would pass out before I could pull the trigger. I didn’t have the courage to be sober and try to kill myself with a gun because you overthink everything. But I figured if I could get high enough, then I could do it.” She was in and out of jail, always for fighting. “The second I felt like someone was going to hurt me,” Vincent says. “I would just fight.”

She began to get her life together when she started training with Kent Ward at City Boxing in New London, Connecticut. Vincent won the 2011 National Golden Gloves, which should have been the highest achievement of her life, but her mother had died only two days before. Shelly’s mother had been one of her biggest supporters, encouraging her from the start and one of the saddest things for Vincent is that her mother never got to see her fight. By the time Shelly began her amateur career, her mother had already been diagnosed with leukemia and was in and out of hospitals. On her deathbed, she made her daughter promise to never give up on boxing until she was a champion.

One night, soon after Vincent had returned to Connecticut after winning the Golden Gloves, she convinced a friend to drive her to St. Mary’s Cemetery in Norwich. It was 2 AM, and Shelly was too drunk to drive herself. The friend remained in the car while Shelly made her way across the grounds. She had brought her championship belt from the tournament to show her mother what she had accomplished, but when she got to the gravestone she was overcome by anger and sadness. “I was so upset that she couldn’t see I did something good,” Shelly recalls. And so she dropped to her knees and started digging up the grass and dirt with her hands.

“I don’t even know what I was doing, other than I missed my mother and didn’t want to not be with her,” says Shelly. “She was the only person who ever loved me.”

Vincent soon left Whaling City Boxing because she wasn’t getting the attention she needed. She tried out Kurt Reader, who formally trained Vinny Pazienza, one of Shelly’s early boxing icons, but after her pro debut, she began training with Pete Manfredo Sr. According to Shelly, Manfredo Sr. didn’t want to train her at first, because there isn’t any money in women’s boxing, but she stuck around his gym until he relented.

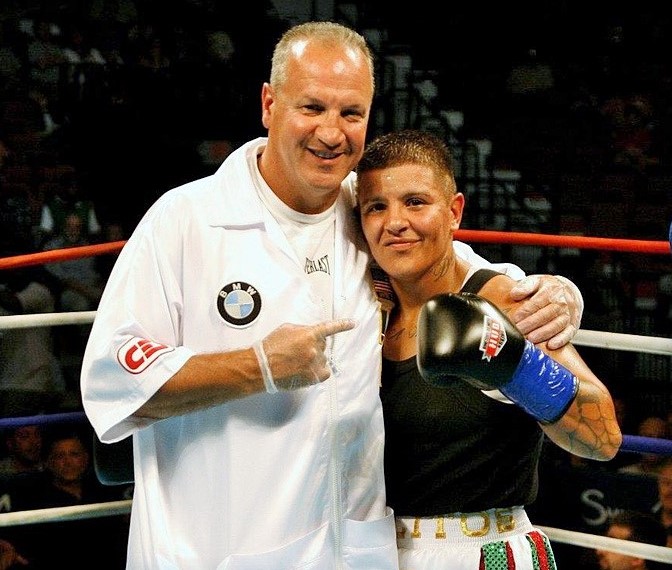

“Pete’s like my dad,” says Shelly, who never had a father. “We have our good days, our bad days. I make him do all the stuff he said he’ll never do. But if I’m not with Pete, I’d be retired, because when you click with somebody and it works, you can’t change it.”

“The style Kurt Reader was giving her was a moving style,” Manfredo Sr. says. “But she’s short, and I made her a lot more aggressive. It seemed to work.”

Under Manfredo’s tutelage, Vincent finally got her life and professional career together, stacking up 18 consecutive wins and becoming the ‘b’ side of the first female fight to be televised on a Premier Boxing Champions undercard.

Prior to 2016, the American public had the chance to see women’s boxing on live television when Amanda Serrano fought Fatuma Zarika in May of 2015, a fight that was aired by CBS. And an August 2015 fight between Maureen Shea and Yulihan Avila was available on pay-per-view. Meanwhile, Claressa Shields would win her second Olympic gold medal on the very same day as the Hardy vs Vincent fight. However, the hype surrounding their match, due to the historic deal with PBC and the public rivalry, made Hardy vs Vincent arguably the most important female fight of the past decade.

There was very little time to prepare for the fight, just over four weeks.

“I couldn’t wait for it to be over,” says Jennifer Salinas. Salinas and Vincent were living together at the time and Salinas had to put her own training and career on hold. “Everything we did was about the Heather fight, you know, from the minute we woke up, from the preparation, the eating, everything was about that fight. And then the interviews and then whenever she would do public appearances. I was so upset. Emotionally, I disappeared.”

But Salinas made it through and was there to support Vincent on August 22, the night of her historic ten round battle with Heather Hardy. From a fan’s perspective, the fight was one of the most entertaining boxing matches of recent years, male or female. But it was a different story for Salinas, who was in Vincent’s corner.

“What happened that night was very hard for me to watch,” Salinas says. She had been with Vincent since 2015 and didn’t support her verbal bullying and theatrics. “Because I remembered the times that Shelly and I talked about how she needs to bring it down a notch because anything can happen. And Hardy was landing some dumb shots, shots that should have never landed on Shelly. I’ve never seen uppercuts so badly thrown, and Hardy manages to pull it off. She throws the dumbest uppercuts I’ve seen in my life. I mean, she doesn’t sit on them, she doesn’t protect herself, and they were landing.”

“We went in there and fought that fight and did not leave a drop outside the ring,” Hardy says. “Like all ten rounds was heart, just non-stop, and more action than probably 90 percent of the fights that you see on PBC or Showtime now.”

Hardy won the bout by majority decision and Ring Magazine would later declare it the best female fight of 2016. Roughly 6 million viewers watched Spence vs Bundu primarily because NBC aired it immediately after the U.S. Olympic basketball game. But the fans who had come to the Ford Amphitheater that evening had not stumbled in there by accident, like many of the TV viewers.

“Errol Spence is pound-for-pound maybe the best fighter in the world, but there was a rainstorm, and the Hardy vs Vincent fight didn’t happen until afterwards,” notes DiBella. “But 70% of that crowd was still there. A good portion of the ticket sales were because of them, and the people stayed through a rainstorm after the main event to watch that fight.”

The main event on a boxing card traditionally goes last, but in this case the final fight of the night was Shelly Vincent vs Heather Hardy. “They were positioned like that because it helped me sell the fight,” says DiBella. “Put the girls on last because it’s going to keep a lot of the crowd beyond the main event.”

In other words, Hardy vs Vincent was used to keep people in their seats. Promoters were building Errol Spence up to be one of the great new boxing talents, and that narrative wouldn’t have been as convincing to a TV audience had the Ford Amphitheater been half empty. But not only was the Hardy vs Vincent fight used as a kind of bait, it was relegated to NBC Sports Network, where it attracted fewer viewers.

“Most people didn’t know who Errol Spence was until this fight,” says Devon Cormack, Hardy’s trainer. “Everyone tuned in because they wanted to see these ladies fight, so they tuned in early to see it but instead they saw Errol Spence, and they said, later on, on a different channel, you’ll see Heather Hardy and Shelly Vincent. So it was all a setup. We knew it would not come before the main event but I don’t think the public knew.”

Hardy isn’t particularly happy about any of this. “Shelly and I did not make a lot of money for that fight at all,” Hardy says. “We were this groundbreaking fight. I mean, they put us on the Errol Spence card, and they asked us to fight after Errol Spence just so that the crowd didn’t leave. For me, it was like, so I’m the one that put all these asses in the seats and he’s the one getting 250,000 dollars.”

$250,000 dollars. That’s how much the then 26-year-old Spence made. Bundu made only $30,000. And Hardy and Vincent less than him.

“We sold the stadium,” Hardy says. “We sold that show, and I barely cleared ten grand for that fight.”

When Hardy says she and Vincent “sold that show,” she means it literally. Promoters don’t see much of a chance of making their capital back on female fighters, so the women have to actually go out and sell tickets. Hardy often sells upwards of ten thousand tickets for her fights, which pays her purse, plus her opponent’s purse and expenses. So even though DiBella doesn’t make much from her fights, it also doesn’t cost much either.

“We were expecting doors to be opened. And you know what? It didn’t happen,” says Hardy. “Me and Shelly got on the phone after [our fight] and we were like, you know what? They put us out there to fight with each other, to argue with each other, to accept less money. For what? Like what are we doing here? I’m not doing this again to put money in someone else’s pocket.”

“Let’s ask for something reasonable,” Vincent recalls saying to Hardy during their phone conversation after their fight. “And then we can prove those views were because of us. Because Errol Spence fought on PBC cards probably five or six times. He never got those numbers. Those numbers were because of me and Heather.”

“You take a girl from Canada, like Jelena [Mrdjenovich]who has WBA and WBC titles,” Hardy says. “She refuses to fight for less than 30 or 40 thousand dollars because that’s what they pay her in Canada. That’s what they’ll pay her in Mexico. That’s what they pay in Argentina and Switzerland.”

But in America, it seems, they just keep exploiting women knowing that they can get away with paying them little or no money.

“You want to give us a rematch?” Hardy says. “Then you give us a rematch where we’re the main event. You give us a rematch where we’re getting paid what we actually deserved to get paid the first time. We both put our undefeated records on the line to take a step for women’s boxing and neither one of us have gotten any kind of due for it.”

For Vincent, though, receiving fair pay is less important than making sure the rematch happens. She wants to avenge the first fight, which she views as a robbery. Vincent even claims that Heather has gone back on her word and has out-priced herself for a rematch. According to Vincent, they could have fought on April 29th at Nassau Colosseum, but the fight fell through. Hardy is adamant that nothing has been offered to her. But if an offer was made she would hold out for more—not just for herself, not just for Shelly, but for the future of women’s boxing.

Vincent’s trainer, Pete Manfredo Sr., says he has always gotten along with Lou DiBella. They’ve done business on a number of occasions, and DiBella promoted Manfredo Sr.’s son, Peter Manfredo Jr. “My relationship with Lou DiBella is good. But does that do anything for promoting Shelly Vincent against Heather Hardy? I don’t know. I would like to say yes, but if it did we would have probably had the rematch already.”

Manfredo Sr. can’t understand why it hasn’t happened. “Maybe it’s DiBella,” he says. “Maybe it’s Hardy. Maybe it was Shelly not being in the gym. I really don’t know. They kept saying, ‘Yeah we’ll do it again.’ Months went by, she took some time off. I don’t know if it’s a monetary question or they’re trying to wait for her to get old, I have no idea.”

“People are always quick to attack promoters,” DiBella says. “The promoters aren’t the ultimate power. TV is. This is a shitty business. By definition, promoters are degenerate gamblers. We’re all sitting there gambling on the future success of a fighter.”

The simple fact is that television networks are offering less money to women boxers. “When you have Showtime offering shit money for a fight, the promoters are going to give us shit money in return,” Hardy says. “It’s not really the promoters fault. I don’t think the networks are returning.”

“It’s a disgrace that I haven’t been able to get a network to pay real money to buy a rematch of what was a sensational fight,” DiBella says. “There’s a tremendous story to be told about who Shelly is, about who Heather is, about what they’ve both been through. The fact that I’ve worked hard and can’t sell that rematch is a fucking disgrace.”

Dibella believes things will change for women’s boxing at some point. But he doesn’t know if he’ll be in a position of power or significance when it does eventually change. “If this whole paradigm of the boxing business doesn’t change dramatically, I certainly don’t see myself in it,” he says. “I’m not going to die in the saddle like Don King and Bob Arum are likely to do.”

DiBella has diversified his life. He is president of two minor league baseball teams, has produced multiple feature films and documentaries, and he’s even published books and he may disentangle himself from the sport before female boxers win their fight for equality. However, he was around this year to witness one important milestone in women’s boxing.

On March 10, 2017, ShoBox aired a match between Claressa Shields and Szilvia Szabados. It was the first time a premium network aired a female fight as the main event. It’s impossible to think of this achievement as being disconnected from the historic Hardy vs Vincent battle, which did so much to get fight fans talking again about women’s boxing. Which only makes it more regrettable that Hardy and Vincent won’t get to profit from what they helped create. It’s been over a year and still no serious movement has been made towards realizing Hardy vs Vincent II. And now the excitement in women’s boxing world has shifted to the young crop of female Olympians who are just beginning their pro careers.

Still, Vincent hasn’t given up hope. Returning to her old antics, she crashed the weigh-in for Hardy’s MMA fight against Kristina Williams. Hardy subsequently lost to Williams, her first defeat as a professional fighter. Perhaps now she’ll be a bit more eager to come back to boxing. If she does want to return, Vincent’s ready for her. But there isn’t an open window on the rematch happening. Vincent is getting up there in age and is starting to realize it.

“It’s a lot harder to stay in shape, fighting shape, when you’re putting the age on,” Manfredo Sr. says. “I had her when she was 34, even younger than that. Now she’s going to be 39 coming up on her next birthday. If she’s going to fight Heather, she’s going to have to fight her soon. This should have been done already.”

Boxing fans are used to seeing unexciting matches between male boxers, fights full of tentative movements and holding and mismatched styles. Even though they are rarely showcased, matches between female fighters are rarely boring. Manfredo believes he knows why.

“The women know they only have one chance and they’re gonna give it their all. That’s what I like about ’em, you know?” — B.A. Cass

Ed. Note: Since this article was first published, Hardy and Vincent battled a second time in October of 2018 and in Madison Square Garden. Hardy won a ten round unanimous decision.

I was at the Vincent vs Hardy fight. The article overlooks the fact that the crowd sat basically silent, maybe some polite cheers, for the men’s fights (their small cheering sections that they brought with them aside), but filled up and went insane for the ladies fight. There were people sitting in my section that only went to the fight casually and had planned to leave when the ladies came out, but wound up staying because the crowd was going nuts every time Vincent or Hardy would come up on the screen so they wanted to see what it was all about. At one point one of them turned to me and said, “This is the most amazing fight. Why haven’t I heard of these two before? Why aren’t they on TV all the time?”

The fact that Spence made $250k for that fight, which was nothing special and no one was all that into, vs what Shelly and Heather made, who both literally owned that arena and had everyone on the edge of their seats, is a travesty. Anyone who was there would have thought the ladies fight was the main event and they got paid the most. It was the most exciting, had the most fans and was fought with more heart than any of the other fights that night. And, Vincent’s fans all mostly traveled from MA, CT, and RI to be there for her. That is how much people love women’s boxing and both these women. It’s no joke, and the powers that be need to give them the respect they are due. It’s such a shame.