On Leon Spinks

In mourning the death of Leon Spinks one week ago, one is not lamenting the loss of “a great fighter,” as some, moved by sentiment, have called him, as much as one is left to reflect on the cruel and unforgiving nature of professional prizefighting and the passing of time. His family and those who knew him aside, the sense of loss at his death is as much, or more, for a particular era, a unique and more innocent time in sports and popular culture. And it is also for the colossal figure who, more than all others, defined it.

Leon Spinks would likely be little more than a footnote in boxing history, an Olympic champion unable to sustain the necessary focus and discipline to achieve success in the pro game, if not for the fact he became the unlikely beneficiary of an aging legend’s need to stay in the spotlight and keep banking huge paychecks. When we mourn Leon Spinks, we are also mourning Muhammad Ali.

In the original Rocky, the Oscar-winning film of 1976, the same year Leon won his gold medal, and the only movie in the series that can be taken seriously on any level, the heavyweight champion of the world, one Apollo Creed — his character a homage bordering on satire of Ali — searches for the right angle to promote his next fight, to make it something more than just another title defense. He decides an unranked contender being bequeathed a wholly unexpected title shot is the story that will sell tickets, the promotion dove-tailing with the year’s bicentennial celebrations. But Creed makes the mistake of spending more time on promotion than on preparing for a fight and he pays the price in the ring.

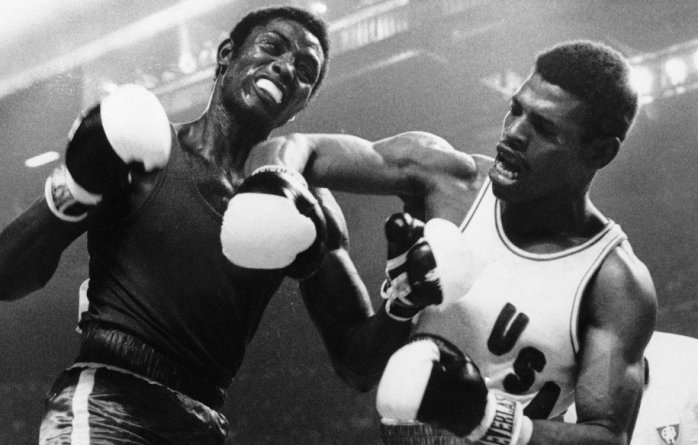

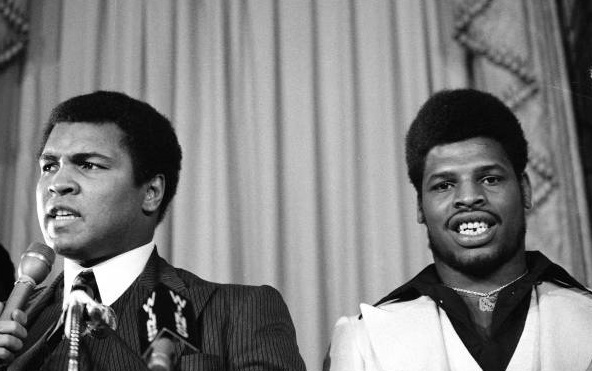

Life imitated art two years later when heavyweight king Muhammad Ali decided that Leon Spinks, with a record of 6-0-1, could serve as both an intriguing opponent and an easy win. The promotional angle hinged on Leon’s Olympic success and the idea that Ali, himself a gold medalist who had defeated fellow Olympians Floyd Patterson, Joe Frazier and George Foreman, would prove himself the ultimate Olympic boxing king by humbling the newest Olympic champ. But the unwieldy conceit gained little traction with the media and instead Ali faced difficult questions as to why Spinks, and not Ken Norton, deserved the next crack at the world title.

As a result, Ali stopped talking and instead of gold medals and Ali’s glorious wins over former Olympic champions being the theme of pre-fight hoopla, it was the unexpected silencing of “The Louisville Lip.” Ali later confessed to being embarrassed by the whole affair, admitting that his silence came from knowing the match-up was indefensible and, presumably, uncompetitive. How could a boxer with only six pro wins represent any kind of challenge? Needless to say, such a perspective isn’t likely to lead to putting in some extra miles of road work during training camp .

Of course we now know that by 1978 Ali was in steep physical decline, if not in the first stages of Parkinson’s Syndrome, all the grueling wars and bruising sparring sessions catching up to the fighter who had become a living legend. But if “The Greatest” was something less than fighting fit when he stepped through the ropes in Las Vegas in February of 1978, Leon Spinks was primed for combat, ready and willing to take full advantage of this unexpected opportunity. Significantly, he was also twelve years younger.

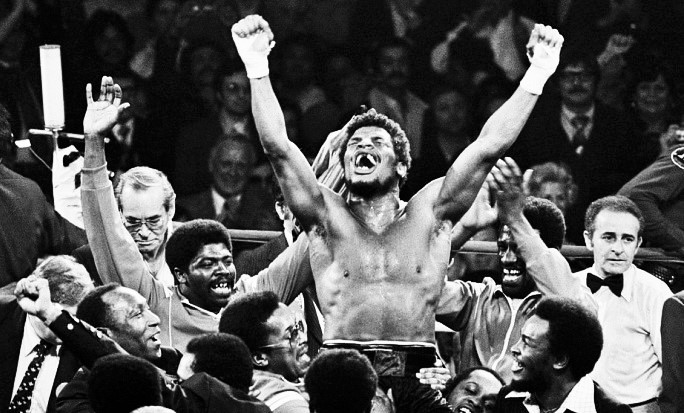

What followed was a fifteen round war between a proud but aging prizefighter whose speed and reflexes had deserted him and a determined, tireless swarmer who, in addition to being younger and in the best condition of his life, had nothing to lose and everything to gain. And if the match-up and the circumstances surrounding it echoed Rocky, so too did the bout itself, with the unyielding challenger showing the lionized champion no quarter, even down to a hugely dramatic final three minutes that saw two exhausted warriors taking turns landing their best shots. In the movie, Apollo Creed is on the ropes, almost finished, when the last bell rings. In real life, Ali too was on the ropes, badly hurt, absorbing punishment, when the final bell tolled.

Such was the impact of Spinks’ upset win, that it was hailed as 1978’s Fight of the Year, despite the fact that four months later Larry Holmes and Ken Norton gave us one of the great donnybrooks in all of boxing history. But such was the shadow Ali cast over the entire sports world that no one thought to question this; after all, the television audience for Ali vs Spinks dwarfed that of Holmes vs Norton.

Of course, it’s difficult now to fully comprehend how big Ali was at that time. Few people, even those with little interest in sports or boxing, did not take a keen interest in the drama that was Muhammad Ali’s life and a humiliating loss to Spinks was a new, dramatic plot twist, not to mention headline news. It was also the high point of Leon Spinks’ career. He would spend the next several years trying to regain the form he showed against Ali, but it was as if he had caught lightning in a bottle on that one fateful night, only to lose it somewhere amidst all the post-fight celebrations.

This would become the predominant theme of Leon Spinks’ life and career as not for nothing did he earn the moniker “Neon Leon.” His distinctive visage and that infectious grin appeared frequently in nightclubs and on disco dance floors, a growing entourage following him wherever he went. The new champion’s car accidents and various misadventures became fodder for the tabloids and the late night TV monologues, and soon the stories began to surface of him disappearing for days from training camp before his New Orleans rematch with Ali, even his bodyguard, Mr. T, unable to locate him.

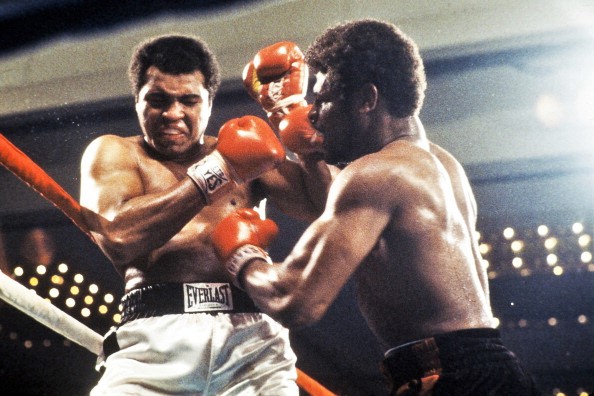

The lack of professionalism and serious focus extended to the rest of Leon’s team and in the dressing room before the big rematch at the Superdome, the champion’s handlers had to borrow buckets and a protective cup from undercard fighters. During the match the farcical scene in Leon’s corner, with various people shouting instructions and vying for his attention, compelled trainer George Benton to abandon his fighter after the fifth round and return to the dressing room. Ali regained the world title with a one-sided decision win.

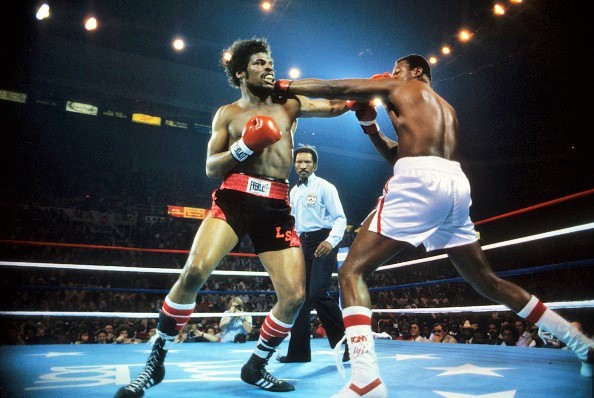

In the aftermath of that defeat it became difficult for fight fans to know what to make of Leon Spinks. No one could question the heart and hustle he displayed in that first battle with Ali, but, in his next fight, unknown South African Gerrie Coetzee found him exceptionally easy to hit and stopped him in one round. A win over hulking Bernardo Mercado suggested Spinks might have rediscovered his former fire and some even gave him a solid shot to upset champion Larry Holmes in 1981, but he was battered and stopped in three rounds. Few could know it at the time, but that was the end of Spinks’ rather brief run as an elite-level prizefighter.

By all accounts the downfall of Leon Spinks was his love of a good time. His brother Michael tried in vain to get him to walk the straight and narrow, chasing after him while trying to chase off all the leeches and hangers-on. The effort almost sabotaged the younger brother’s career before Michael, also an Olympic gold medalist, got himself together and went on to win world titles in both the light heavyweight and heavyweight divisions. It was Michael who put an end to the championship run of Larry Holmes and gained a measure of revenge for his older brother.

Meanwhile Leon had dropped down to compete in the cruiserweight division but Carlos De Leon and Dwight Muhammad Qawi humbled him and by this time he was a name only, no longer a legit title threat. Still, he fought on and did not retire until 1995, his final record 26 wins against 17 defeats. He had taken far too much punishment to escape the long-term health problems which afflict so many fighters, especially the ones, like Leon, who partied as hard, or harder, than they ever trained.

Of course there was much more to Leon’s life than just boxing. He served his country as a marine, and he was a husband, father and grand-father. He endured the great pain of losing a child, his son Leon Calvin murdered in East St. Louis. But it was his boxing career that defined him, that put the name Leon Spinks in the history books. And it was, in turn, that great upset win over Muhammad Ali which defined that career. No one who witnessed it will ever forget the moment when announcer Chuck Hall uttered the words, “… and new …” and millions around the world gasped in astonishment. It was a shocking instance of life imitating, and then exceeding, art, the ultimate “Rocky” moment, a 6-0-1 novice defeating not just a champion, but a legend, Muhammad Ali, “The Greatest.”

So no one should be surprised that when the news came, it hit hard. The death of Leon Spinks shook the fight game this past weekend to its core. You could feel the impact as fight fans the world over paused and reflected. As I say, that reaction wasn’t only for Leon, but for another time, a different era, for an astonishing upset win, and for the great man whose shadow boxing will never escape. Rest in peace, Leon. Now you and your great rival are together. — Neil Crane

Nice article, thank you!