Je Me Souviens

The Place Bell is situated a five-minute walk from the doors of the Montmorency metro station in Laval, just north of Montreal. But when the temperature is -15 celsius, as it was last Saturday evening, you’re forced to walk at a brisk pace, regardless of the thickness of your coat. Even factoring in the cold, the street looked eerily desolate then, especially considering that just a couple hours later some nine thousand fight fans were expected inside the Place Bell to witness a world-title boxing match. But no one lingered outdoors without purpose on that night; the only people I spotted on my walk were a handful of smokers, huddled right outside the doors of the hockey arena, making the most of a break between undercard fights. With the wind blowing nonstop into my eyes, I was forced to keep my head low, so the only other thing I noticed as I walked was a three-word phrase, which kept reappearing over and over.

Je me souviens.

Quebec’s official motto is stamped on the license plate of every registered car in the province, and the Place Bell’s parking lot was full of them. By itself, the phrase means “I remember.” But the Quebecois, masters of the passive-aggressive jab, have ingrained the motto with a deeper meaning. The full line from which the phrase is taken is: “I remember that, born under the fleur de lys, I lived under the rose.” You see, “Je me souviens” is at once a shout out to Quebec’s cherished French heritage, and a dig at the British Empire that colonized the territory in the second half of the eighteenth century; the latter being an unwelcome historic event that holds perennial sway over the Quebecois’ attitude towards anything British, towards anything foreign, really.

Ever since, as a response to outside pressures to assimilate, Quebec has resorted to multiple defense mechanisms, one of the most prominent being a prolific production line of cultural content. The province generates more music, films, TV shows and books than several small countries put together. But more relevant to this piece, is the fact that sports are an integral part of the mix. It’s well known Quebec is one of the premier breeding grounds in the world for hockey players, as is the fact the beloved Canadiens are the most historically successful team in the NHL.

But in recent years, Quebec has also become home to an ever-growing stable of prizefighters, all of them eager to become recognized on an international scale as a high-quality export of La Belle Province. More importantly, Quebec sports fans have enthusiastically tagged along for the ride, filling up venues of all sizes all over the territory, forking over money and supporting local fighters. For further proof of boxing’s increasing relevance to Quebec’s sports identity, look at the robust boxing coverage in French-language media. All this points to a single conclusion: the potent mix of boxing and nationalism has cast on Quebec sports fans the same kind of spell it has cast on entire countries like Mexico and Puerto Rico.

When a Quebec prizefighter steps into a boxing ring, whether the fight is taking place inside the Province or on foreign grounds, he knows he is being watched by hundreds of thousands of his fellow Quebecois, and this is a bond that grows stronger and stronger with each fight card and with each new talent that steps through the ropes. As much was evident to me last Saturday night in Laval; while there have been other boxing cards staged in Quebec that assembled larger crowds than the one at the Place Bell, I don’t remember seeing one that was more enthusiastic, or that supported the local fighters as fiercely and as proudly as this one did.

Breezing past the metal detectors after entering the venue, feeling very relieved to be in from the freezing cold, I found myself shivering and sniffling in front of the two very attractive and sympathetic young women distributing the press credentials. One of them ticked my name from a list and gave me my pass, while the other handed me the card program. As I turned away, I noticed both of them looked at me–the sniffling Mexican who obviously can’t handle the cold–like one might look at a three-legged puppy.

It took me more than a few steps to get all my affairs in order: put the program in the laptop bag; place your gloves inside the coat’s pockets; zip up the pockets so the gloves don’t fall out; take the laptop bag off your shoulder so you can take off your coat; hang the press pass around your neck; hang the laptop bag back on your shoulder; and, finally, hold your coat like a pile of lumber under your arm. There. Now you look like less of a nerd. If you could stop your sniffling that would be great.

I made my way to the floor of the Place Bell, a modern, newly built facility that is essentially a mini-me version of the Bell Centre in downtown Montreal. The HBO crew was already hard at work, various cameras and lights pointing in all directions, lines of monitors crowding the entire west area of the floor, and Max, Jim and Roy hanging out ringside and doing whatever it is they have to do before the start of a broadcast. I walked past and asked an extremely cordial security type where the hell I was supposed to go. “On the other side of the ring, monsieur, you will find your seat.” Excellent.

As I approached the opposite side of the ring, I walked past the exclusive VIP area, which is where the richest, best-dressed people are to be found on a night like this. This is a fixture of big fight cards in Quebec, and I have yet to see it at venues outside of La Belle Province. If you’re a big shot and you want to see a high-profile fight in Quebec, you get the chance to reserve a whole table, seating up to a dozen of your peeps, along with bottle service and fancy food. In short, you get the works. This is also where the babes with the highest stilettos and the most eye-catching dresses hang out. The scene is both confounding and alluring; it’s like a fashionable night club was somehow air-lifted and set next to a boxing ring in a hockey arena.

To my right I spotted a familiar figure sitting near press row. Manny Montreal, sporting a wide smile and the requisite ‘The Fight City’ t-shirt, was following the ring proceedings closely. I put a hand on his shoulder, and upon recognizing me, out of the corner of his smile he let out a “Took you long enough!” “What time did you get here?” I asked, knowing the answer beforehand. “Since they opened the doors, same as always,” he answered, redirecting his attention back to the ring.

Manny is never late to a fight card if he can help it; he respects the game too much to miss even a single undercard match. He is by far the most fanatical fight freak I know. At this point he started giving me the rundown on every single bout that had already concluded, and when he was done, he started sharing insights into the fighters working that night–how their training camps went, what would be their likely next steps, what’s their potential ceiling, etc. Suffice to say, Manny knows his stuff.

He was giving me all these updates at a pace so quick it was like he was firing bullets of facts out of a machine gun so I tried to keep up as best I could; and not only was he doing it out of a sense of camaraderie, it also reminded me of how much he loves talking shop. He then offered to show me around the place, take me to where they were handing out free filet mignon, serving the free coffee, and where I could leave my coat. I thanked him for his generous offer, but I chose to take out my laptop then and there as I was clearly way behind everyone else. He then took my coat to the media room to get it out of the way; space is always at a premium on press row.

There was supposed to be a spot for me around there somewhere, reserved by a printout of my name on a sticky piece of paper, but I arrived too late, and all the seats at the press table were taken. The people from TVA and Radio Canada and RDS were all radiating gravitas from their seats in the first of the two press rows, while the lowly bloggers and print media writers worked from the second row. Manny and myself occupied chairs right beside them.

I opened my laptop and started taking notes, helped greatly by Manny’s running commentary. The sixth round of the Custio Clayton vs Rafael Coria fight was underway and as I struggled to get my bearings my mind was going in six directions at once. Whoa! What a perfect venue for boxing, not a bad seat in the house! Wait a second, there are at least three more undercard fights before the main event, and the venue is already full? How many matches did I miss again? Hey, isn’t that Bernard Hopkins over there? Wait, what did Manny just say? Need to get him to repeat that name. Oh, nevermind, he’s talking to Tyson Fury.

The Gypsy King, all 6-feet-and-9-inches of him, looking–dare I say it?–dapper, draped in a stylish black suit, stood right next to us, talking with Manny, a quick chat between friendly acquaintances, you see. “Last night I got a call,” Manny said to me once Fury left; “Tyson Fury wants to work out; do you know a place?” Did he know a place? Of course he knew a place. He’s Manny Montreal.

Through the next five fights, including the main event, Manny darted from one location to another as he spotted fighters, trainers, promoters and personalities. Camera in hand, he was always ready to conduct mini-interviews and get some photos at the shortest notice. Meanwhile, I tried to take in as much of the ring action as possible. But through all this, the one thing that never faded long from my consciousness was just how into it the crowd was. They cheered loudly every time a home fighter was introduced, and they cheered even more when he landed a solid punch during the fight. They danced and drank during intermissions, and when finally Michael Buffer entered the ring to commence the HBO broadcast, the atmosphere was absolutely electric.

The bad news on this night was that this most primed of audiences, eager as they were to find a Quebecois hero to put all their weight behind and single-handedly push into stardom, would fail to get anywhere close to the satisfying climax they deserved. Foreshadowing of sorts appeared in the form of the opening bout of the broadcast, where the gifted and devilishly quick Yves Ulysse Jr. jumped out to a tremendous start, scoring three knockdowns over Cletus Seldin in the first three rounds of their fight. The crowd was ecstatic at the end of the third stanza, sensing an early finish and a star-making HBO performance for one of their own and one of Quebec’s most promising talents.

But in the middle rounds, Ulysse–fresh off a controversial decision loss to Steve Claggett and thus seeking to avoid at all costs the stigma of consecutive defeats–drastically reduced his punching output and instead turned the ring into a race track. In his mounting frustration, Seldin started spending less and less time chasing Ulysse and more and more time throwing his arms in the air and complaining to the referee. After a while, the ref called both fighters to the center of the ring and reminded them that they were, in fact, in the middle of a prizefight, and if it wasn’t too much trouble maybe they could throw a few punches for the sake of this poor audience right here. In the final two rounds, Ulysse upped the tempo again, and put the finishing touches on what proved to be a wide points victory.

“I’m a very happy guy right now,” said Manny when he returned from talking to Ulysse once the fight was over. “Getting some great stuff,” he added, which meant Michael Carbert, our fearless leader and founder of this esteemed site, would be happy too. But Manny’s upbeat mood was as much about the positive results for the local pugilists as it was about getting some high-quality photos and video. After all, being the devoted chronicler of the Montreal fight scene that he is, Manny has seen these athletes become the fighters they are by watching them train and spar month after month, year after year, in gyms all over town. A card like this one, stacked with local talent that he’s seen reared and nurtured, is as close to a perfect evening as it gets for a fight freak like Manny.

And he clearly wasn’t the only one enjoying himself. Remarkably, despite the loads of fights and the inevitable ups and downs that come from watching several consecutive boxing matches, the audience never lost track of the main event, and were able to not only sustain, but build up their energy level through the night. Every time the huge screens above the ring showed David Lemieux and Billy Joe Saunders at different stages of their pre-fight preparations — arriving to the venue, warming up in their dressing rooms, then getting their hands wrapped — the crowd alternated between cheering and booing with increasing intensity. By the time the main event arrived, the audience was more than ready to burst into spontaneous combustion.

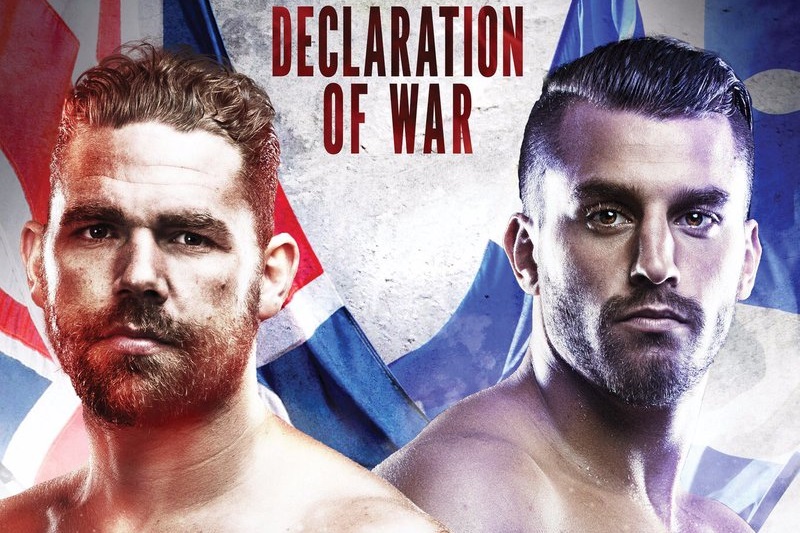

The closest they came to that was when David Lemieux made his appearance on the high stage placed behind the VIP tables. Behind him were two giant vertical screens that showed his face and his name in the foreground, and a Quebec flag in the background. When Saunders was introduced, a similar image flashed behind him, with his own face and name in front of a Union Jack. These images immediately brought to mind the huge banner that hung behind Ivan Drago as he commenced his ring walk in the climactic fight of Rocky IV. The link between boxing and nationalism, both suggested and implied ever since this bout was first announced, at last took its rightful place under the spotlight. Quebec vs Britain. Here we go, one more time.

Once the opening bell rang, the proceedings in the ring were tense and hesitant, typical for the first round of a championship bout. But very soon, in fact still within the opening three minutes, it was clear to all that David was at a clear disadvantage in, well, pretty much every department. Billy Joe was quicker, more mobile, and smarter in the ring. He also seemed better prepared than Lemieux, both physically and mentally. While Saunders went on to deploy his stick-and-move strategy beautifully for 12 rounds, Lemieux appeared lethargic and apathetic for long stretches of the bout. And while Saunders knew exactly how to neutralize Lemieux’s best weapon–his coma-inducing left hook–David had no back-up plan once his vaunted left was rendered useless.

The result was, for so many of the assembled, a wholly unexpected scenario. The majority of fight fans at the Place Bell had expected a rusty Saunders to have problems mounting an effective offense and had hoped that Lemieux’s power would then decide the outcome. But the opening rounds proved us embarrassingly wrong. We had underestimated Saunders just as badly as we had overestimated Lemieux.

Ideally, as far as the crowd was concerned, Lemieux would’ve confronted this adversity and found a way to overcome it, thus making victory all that much sweeter and worthy of remembrance. Unfortunately for all the Quebecois watching, this scenario was not to materialize either. As the rounds piled on, Saunders asserted himself over Lemieux, and over the entirety of the Place Bell, with shameless ease. Once the realization hit us that Lemieux was in over his head, the energy was sucked out of the arena. After all the build-up, the main event had turned into a huge let-down.

“At least it’ll make for a short press conference,” Manny remarked at one point during the middle rounds. For everyone who was rooting for Lemieux, and for those merely hoping for an exciting contest, hearing the bell to each subsequent, monotonous round felt like popping open a flat, warm beer and being forced to gulp it down.

After 12 rounds, Saunders had shut out Lemieux and earned a wide points win. But his mocking of Lemieux, his showboating during the fight, and his comments after the contest, endeared him to absolutely no one in the building. Not that the Brit cared to cozy up to these touchy Quebecois. “I know you’re booing me because I whipped your fighter’s ass, but that’s boxing,” he shouted into Max Kellerman’s microphone, pouring a bucketful of reality over all who had underestimated him. Lemieux, for his part, blamed a hand injury and Saunders’ “running” for his lame performance. While most fans outside Quebec will label him a sore loser for refusing to acknowledge Saunders’ superiority, his countrymen may see in his refusal to concede an admirable tinge of that infamous Quebecois pride that binds them all together.

Talk about an anticlimax. Thousands of pissed-off Quebecois left the premises faster than you can say Bonjour, hi!, murmuring nasty things in French, unless they were drunk, in which case they were yelling them. The lights were almost immediately turned all the way up so the crews in charge of dismantling the lighting rigs and the boxing ring and the stage and all the other props of the production could get to work asap. The mood at the Place Bell was so sour that Manny turned out to be wrong about something else: we didn’t get a press conference at all, the organizers cancelling the whole thing rather than give Saunders another chance to gloat. Revenge against the Brits would have to wait. But that’s okay. There will be other chances to channel historic wrongs into spectacle, sports, and money. The fighters and the venues might change but, for a nation as proud of their fighting tradition as Quebec, the forces that drive the boxing narrative will always remain. Je me souviens.

Very soon the only ones still left on the floor were the dismantling crews, and the small brigade of British media interviewing Saunders’ team near the red corner. “The Gypsy King” held court nearby as well, regal in his sharp suit and positively glowing after having witnessed such a splendid outing from his friend and fellow gypsy traveler Billy Joe, answering one question after another, half of them about Saunders’ performance, the other half about his own imminent return to the ring.

Meanwhile, I paced all over the floor looking for Manny, who I assumed was doing interviews and compiling as much information from as many different people as he possibly could. I went backstage looking both for him and for my coat. I texted him, knowing the chances of him responding, busy as he surely was, were effectively zilch, and he didn’t prove me wrong. The clock was ticking fast towards 1:03 a.m., at which time the last metro train left the Montmorency station. I briefly considered leaving without my coat, hoping Manny would remember to take it with him; I could pick it up from him the day after. Stop right there, you moron! It’s minus 20 degrees outside!

“Manny! I need my coat, man!” I said when I finally found him. He had a tired look in his eyes but, despite the anticlimactic main event, he still showed a trace of a smile. “Oh, so that’s why you’re still here,” he said. I followed him backstage, and he led me into the empty media room where a handful of chairs were arranged facing an equally empty, small stage. This is where the cancelled press conference would’ve taken place, and where my coat and Manny’s photography equipment were waiting for us.

We started walking towards an exit when I saw Max, Jim and Roy being rushed out a back exit. Jim stopped in his tracks to yell at the others, “I’ll be right there, guys! Gotta take a whiz!” The phrase sounded extremely odd in Jim’s emblematic voice. Meanwhile, Manny was already a few steps ahead of me, talking to a couple of ladies–producers or reporters of some sort–and they looked immaculate even after a 12 bout fight card: dressed up, but professionally so; hair perfectly done; their makeup flawless. Just seconds ago Manny and I had agreed to take the last metro together, but now he was giving me the same scram, kid! look that my then-teenager uncle used to give me when I was ten and we were hanging out at the mall together and he ran into some hot chick.

I got the hint. I pulled on my coat, rushed out the nearest exit, and half-ran to the metro station while trying to not slip and crack my skull open on the icy concrete. And as I sprinted down the seemingly endless flights of the escalator inside the metro station, in the distance I could hear the rush of the last train of the night. –Rafael Garcia

Photos by Manny Montreal.