Interview With Todd Snyder

An amateur boxer prowling the stands in desperation, looking for a last-second opponent. Silver Gloves competitions filled with anxious fighting novices. “Tough Man” contests brimming with fighters long on courage and short on skills. A frightened boxer having his ring walk interrupted by sudden, uncontrollable nausea. A trio of brothers from inauspicious origins who just might have what it takes to become world-class. Girl-fighters as amenable and good looking as they are tough and intimidating. A boxing trainer channeling his passion for the fight game into an enduring legacy.

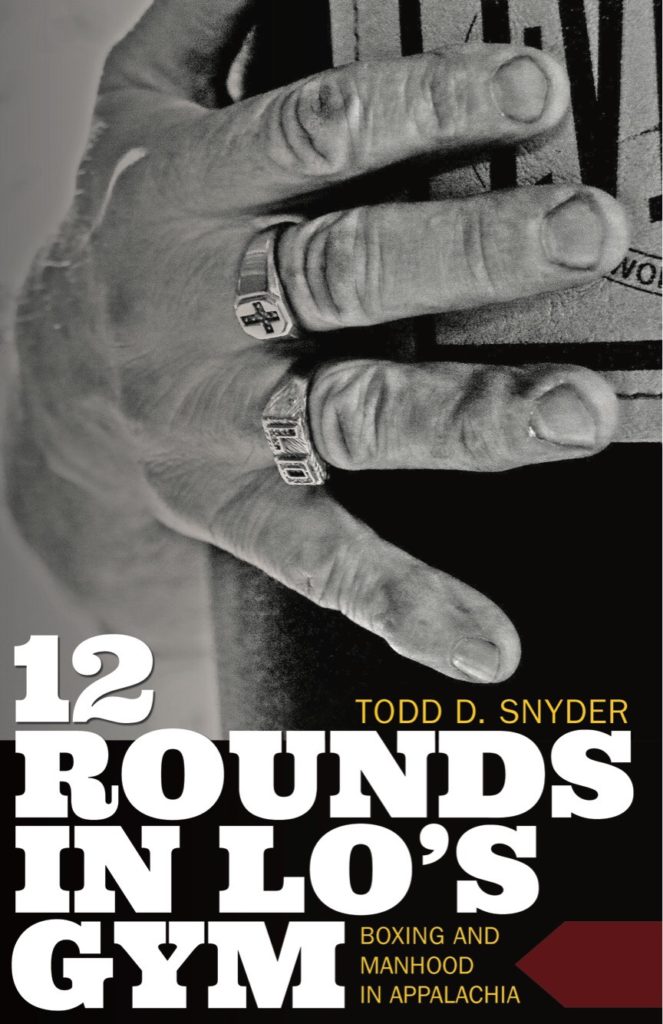

“12 Rounds in Lo’s Gym: Boxing and Manhood in Appalachia” is not a single story, but a narrative composed of dozens of them, all the more powerful for being so encompassing. Relying on an addictive, matter-of-fact prose style, Todd Snyder takes the reader deep into Appalachian country by telling the story of his father’s serendipitous foray into boxing, and with it the story of Lo’s Gym, a den of pugilism nestled away in Cowen, West Virginia, a town of some five hundred people. To do so, he recounts the tales of Mike “Lo” Snyder’s fighters, their dreams and aspirations, and the harsh realities they must face on a daily basis. It’s a moving portrait of hard luck and tough breaks, but also of compassion, perseverance and courage.

Snyder, a professor of rhetoric and writing at Siena College, accrued amateur boxing experience while growing up in Cowen, where he was trained by his father. This, along with his unique voice and storytelling prowess, makes 12 Rounds in Lo’s Gym a unique work of boxing literature. It approaches the sport from the bottom up, showing the impact a boxing gym can have in a community, and the influence that a trainer can have on his pupils, both inside and outside the ring. What follows is an email discussion Todd and I had about his latest book.

Rafael Garcia: The theme that comes to mind when I think back on 12 Rounds in Lo’s Gym is that of underdogs. Just as the fighters trained by your father were underdogs practically every time they stepped through the ropes, you also present the entire region of Appalachia as an underdog, with its people carrying on under difficult circumstances. But the fascinating thing about underdogs is that they represent a contest between romanticism and reality. Your father, Mike “Lo” Snyder, is perhaps the best example of this. At times he appears as a romantic figure with his constant encouragement of even the most hopeless aspiring boxers, or his embellishment of what you call his Beowulf stories. But at other moments he comes across as an unabashed realist, like when he nudges one of his most competent fighters into turning down an HBO undercard fight against Danny Jacobs, where he would’ve served as little more than cannon fodder, despite this being a long-awaited shot at “the big show.” Is this contrast between the romantic and the real sides of boxing something you consciously worked into the book? Or was it simply unavoidable given the subject matter?

Todd D. Snyder: After reading an early draft of the manuscript, a reviewer commented that my father was “coming off as something of a saint.” That particular criticism bothered me. Convincing readers that my father was a martyr or a saint was never my intention. That sort of thing is what keeps me from finishing most memoirs or biographies. I wanted to highlight my father’s flaws, contradictions, and limitations, just as much as I hoped to illustrate his compassion, selflessness, and work ethic. Our values, attitudes, and even our beliefs, are never as fixed as we’d like to admit. We, as human beings, hold tightly to our contradictions. My father was no exception. As I revised the manuscript, looking for ways to turn my father back into a human being, I made it a point to unravel both the romantic and pragmatic strains of his personality. Back in the Lo’s Gym days, you never knew which side you were going to get. If we’d have a difficult show, an event where all of our competing boxers lost their matches, he’d behave as if he were ready to pack it in and close down the gym for good. Then some gangly trailer park kid would walk through the door the next day and my father would swear that we’d just found the next West Virginia Silver Gloves champion. My father saw himself as an underdog. That was a big part of his identity, as both a West Virginian and a local boxing guru. And like most underdogs, he was both a dreamer and a pragmatist. He’d tasted enough disappointment to understand the pain of failure. He’d dealt with enough failure to understand the intrinsic need to escape such pain.

RG: Another recurring theme is that of masculinity and character, perfectly encapsulated by your father’s saying: “I’ll take the guy who has the balls to climb through the ropes and give it hell knowing the odds are against him.” I found it telling that you bring up this memory right after writing about Dustin Wood, a fighter trained by your father, whom you introduce by saying “Dustin wore his fear to the ring like a hooded boxing robe,” as if reinforcing the point that, although it might seem paradoxical, not only do character and masculinity allow fear, they can actually feed from it. Having done some fighting yourself, do you think this turning of fear into fighting fuel is something that can be taught and learned? Or is it something innate to fighters?

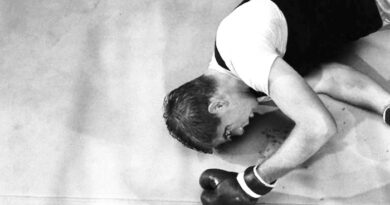

TS: No. The process of turning fear into fighting fuel is not a skill that can be taught. This is one of the little mysteries of boxing that make great fighters special. You can teach a boxer how to step with his jab, keep his chin tucked, throw combinations and slip punches, but you cannot teach the sort of thing that happens to a fighter like Dustin Wood as he makes his way to the ring. What you are alluding to is a character trait, one that is often honed and conditioned by life experience. Much of this is subconscious, I think. There are countless socio-cultural factors at play in shaping such a personality.

Yet, in asking these questions, you bring up a great point. Many outsiders think great boxers are devoid of fear. Anybody that has ever boxed knows the truth. Great fighters, even great trash talkers, are often motivated by fear. And, as you suggested, Dustin Wood was a prime example of a boxer that knew how to turn fear into fuel. Dustin would have climbed through the ropes and took on Floyd Mayweather Jr. if my father had asked him to. He wasn’t afraid of getting hurt or even losing. He wasn’t afraid of being embarrassed. He was only afraid that he wasn’t going to get a fight. Fighting freed him from the fear. I think writers are equally motivated by fear. On a good writing day, a day where I am really in the zone, I am as free as a human being can be. I can muster the courage to address anything and everything about life that frightens or troubles me. I imagine that is how Dustin Wood must have felt when the bell rang.

RG: Jason Bragg was a dependable helping hand at Lo’s Gym, but eventually he became another of your father’s fighters. As you put it: “Jason Bragg’s prizefighting ambitions were a festering sore buried somewhere deep underneath the surface; the blister that finally popped and oozed was decades in the making.” Somewhere else in the vicinity of that passage, you write about the night your dad finally got the words out of Jason declaring he actually wanted to get into a ring: “Jason was a 31-year-old boxing virgin, lusting.” Was this an intentional contrast in imagery between boxing being both something highly appealing and highly repulsive?

TS: My intention was to expose the beauty and horror of our struggle, to provide a nuanced glimpse into life in working-class Appalachia. My literary vehicle for dealing with this subject matter was boxing. However, the juxtapositions you’ve mentioned work well either way. You can accurately describe life in rural Appalachia and the sport of boxing by highlighting such contrasts. One doesn’t need to be a boxing aficionado to be able to see both the beauty and brutality. I’d argue the same for Appalachian culture. In telling Jason’s story, those contrasts showed themselves in more poignant ways, largely because Jason Bragg’s transformation was both spectacular and unexpected.

RG: By the end of the book there’s an unmissable parallel between the coal mining industry and boxing, at least as far as their influence and effects in Appalachia, and in the town of Cowen in particular. Both are presented as extractive–even exploitative–endeavors. While coal mining companies profit from the labor of the workers, they deny them fair compensation, and sometimes even their hard-earned pensions. Similarly, boxing often stacked the deck against Lo’s Gym’s fighters when they traveled to tournaments; at one point you write about a teary-eyed child who has to give up his first-place trophy because of apparent corruption. And yet, it’s undeniable that, just as your father’s fighters took pride in their modest accomplishments, the miners of Cowen also took pride in taking up a dangerous job and doing it day in and day out. Would you characterize the links between Appalachia on one side, and coal mining and boxing on the other, as love-hate relationships? What do they tell us about the character of the Appalachian people?

TS: You’ve touched on perhaps the most difficult aspect of writing about life in Appalachia. Most books on Appalachia take one of two rhetorical paths. Writers either look to pinpoint the exploitation of Appalachian workers, or highlight the degradation of the land, via a critique of the extractive industries or, as was the case in J. D. Vance’s recent memoir “Hillbilly Elegy,” they attempt to justify the poverty found in the region by providing cultural explanations. Industrialism came to Appalachia and the Hillbillies didn’t take full advantage. This sets up a strange dichotomy for many readers from outside the region. One argument wags its finger at the mining industry, and the other wags its finger at the people, blaming them for their own poverty. I wanted to complicate those ready-made arguments about life in Appalachia. Most coal miners could write you a dissertation on the exploitation they’ve witnessed in their careers — unfair pay, benefits, the loss of hard-earned pensions, etc. Yet, you’d be hard-pressed to find a coal miner that doesn’t take pride in his or her work. West Virginians are proud of their coal mining heritage. They’ve signed up for it because mining coal has always been the way. I used to tell it to people like this: coal mining helped pay for my college education, but it robbed my father of his. My father didn’t want to be a coal miner. He had other dreams. And, for a little while, he had the opportunity to live those dreams.

In regard to boxing, my feelings about the sport have evolved over the years. Do I love the sport of boxing? Without question! I admire and respect any prizefighter that has the courage to enter the squared circle. As a writer, there is nothing that inspires me more than a night at the fights. I learn something different every single time. Boxing is both savage and beautiful and tells the story of world history, if you are so inclined to do the research. Becoming a father, however, has, in some ways, changed how I feel about the sport. Do I want my son to become a boxer? No. I do not. Boxers pay for their sacrifice just as do coal miners. Unfortunately, it is those outside the ropes who often benefit the most from this sacrifice, with promoters, managers, and television executives serving as the absentee owners of the extractive industries in such a comparison.

RG: Your father opened Lo’s Gym to reach out to youngsters in Cowen, West Virginia, and to provide them something positive to focus on, a sense of routine and discipline, along with lots of guidance and care. By taking up boxing, many of his pupils got the chance to see things they hadn’t seen before and to learn that the world presented opportunities they hadn’t yet considered. You write of young boxers traveling to other states and visiting big cities for the first time when they traveled for tournaments and amateur cards. But do you think there is something unique about boxing that had a particular impact on your father’s fighters and on the community in general, as opposed to, say, had your father opened a chess club or taught some other sport?

TS: A chess club wouldn’t have much staying power in my neck of the woods. The town of Cowen was literally shaped and molded by the coal mining industry. Workers were brought to the mountainous region for one purpose and one purpose only, to do the dangerous and low-paying work other folks would not do. We are talking about generation after generation of hard working West Virginia coal miners, born into a mono-economy where almost every man in town has to work a hard job. Taking into consideration the geographical isolation found in the region, one can easily see how such an environment fosters certain masculine attitudes. Boxing resonates with folks from around my way because the sport so clearly exemplifies the character traits necessary to survive in a place like Cowen. My father used to tell fighters in the gym, “the hard part about boxing is being tough … and people from Cowen are born tough … so you’ve already got the hard part down.” — Rafael Garcia