The Long Journey Back

The brutal world of pro boxing isn’t necessarily a great place for family bonds to thrive. But the history of the sport is full of father-son relationships, many of them leading to sad, if not tragic, outcomes. One recalls the late Jimmy Garcia being pushed by his dad to fight on against Gabriel Ruelas only to later die from his injuries. Or Mike Rossman having to fire his own father who had been his manager for years. Or Wilfred Benitez being abandoned by a father who may have cheated him of his ring earnings.

Some turn out much better; Robert Guerreo and his father Ruben are an example of a successful family duo. Still, the son must work to find that tricky balance between adherence and securing accomplishments which belong to him and him alone. In the ring, under the great weight of pressure, the strain and the differences are amplified. Vicarious as the relationship may be, finding the space between too near and too far can be a life-long struggle.

Julio Cesar Chavez, Jr., despite his unique, loaded name, is still finding his own way.

Now Icarus falls down head first

the last frame of him is a glimpse of a heel, childlike, small

being swallowed by the devouring sea

Up above the father cries out the name

which no longer belongs to a neck or a head

but only to a remembrance

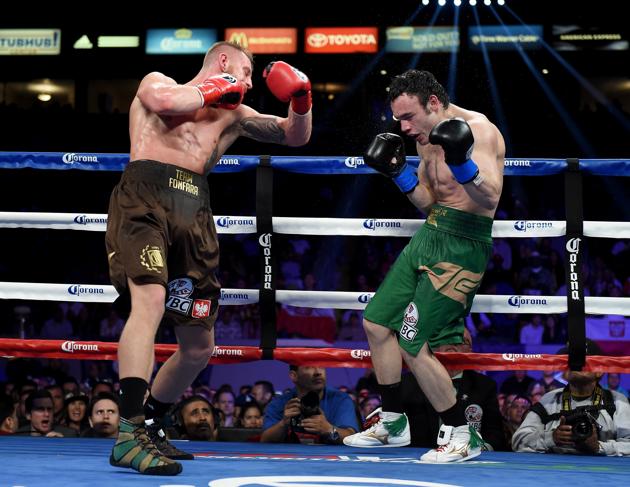

Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, in describing above the tale of Daedalus and Icarus, captures the mix of disappointment and mourning felt by parents when children fail. One could imagine Julio Cesar Chavez Sr. feeling similar dread when his son, his namesake, found himself alone after getting decked in round nine by Andrzej Fonfara and subsequently bowing out, his corner a veritable island of shame.

Chavez Jr., given everything, and yet given nothing; brought along under the watchful eye of Top Rank Promotions, fed easy opponents in the limelight, fudged through some precarious situations before showing substance, and finally serving as a cautionary tale to all fighters intent on faking the funk to the top. Like Icarus, Chavez Jr. needed to avoid aiming too low, and getting too high.

Fonfara knocked “Son of a Legend” back to a low orbit, where Junior now has an opportunity to attain self-affirmation and in a roundabout way bring honor back to the family name when he faces Marcos Reyes on Showtime. It’s a perilous hike back to the top though, as Junior has burned up so much good will along the way and there is healthy doubt he can even make 168 pounds to face Reyes, a middleweight who previously fought at 154.

Living passively in the genetic shade of a Mexican legend is disagreeable to begin with, but walking the same fistic path is like tracing huge footsteps while fearful of veering wayward. Chavez Sr. is not without faults and failures, like staying in his corner against Oscar De La Hoya, or being fortunate to not lose against Pernell Whitaker, and Frankie Randall in the rematch, and alcoholism likely robbed him of the ability to adequately guide his young son. All that noted, whenever Chavez Sr. fell short in any boxing sense, he had an enormous body of work to prop him right back up. But where the elder Chavez is “El Leon de Culiacan,” the younger is more of a paper tiger.

Reyes, 33-2 with 24 knockouts, is the right opponent to give Chavez Jr. a win, as he’s not a difficult target and has been sent to the canvas plenty. Walking around likely near heavyweight between fights, Chavez Jr. should also hold a comfortable size edge when the bell rings, but like a cat currently on life number nine, he can ill afford to falter from here on out. There have been gift wins over the likes of Brian Vera and Matt Vanda, DUIs, dirty drug tests and social media mockery. Chavez vs Reyes could potentially be a nightcap in Last Chance Saloon.

Before the inevitable fall, Chavez Jr. had shown growth as a boxer, battling his way from pay-per-view sideshow to actual fighter, then sincere contender. He hasn’t yet had to overcome all-out disgrace, only embarrassment. It could be that signing with Al Haymon’s Premier Boxing Champions is only to help fund Chavez Promotions, but returning three months to the day from his first stoppage loss could prove to be a grave error. Then again, hiring a new trainer in Robert Garcia and once more re-dedicating himself to serious training may be a genuine first step in a journey toward redemption, but there’s a long, long way to go yet.

Julio Cesar Chavez, regarded by some as the best ever Mexican fighter, retired in 2005 with a record of 107-6-2. He is a massif on the country’s boxing landscape. Junior, 48-2-1 with 32 knockouts and one No Contest, is a small fissure in need of a seismic event to grow his legend.

If Chavez Jr. is content to be an average boxer who rode the fringe of “good,” that’s his choice. But should he aspire to become his own lion, to manage his own destiny as a respectable fighter who glared back when the darkness of the jungle stared into him, sending an opponent like Reyes packing is a start. But the dearth of souls believing he can do so is telling. — Patrick Connor