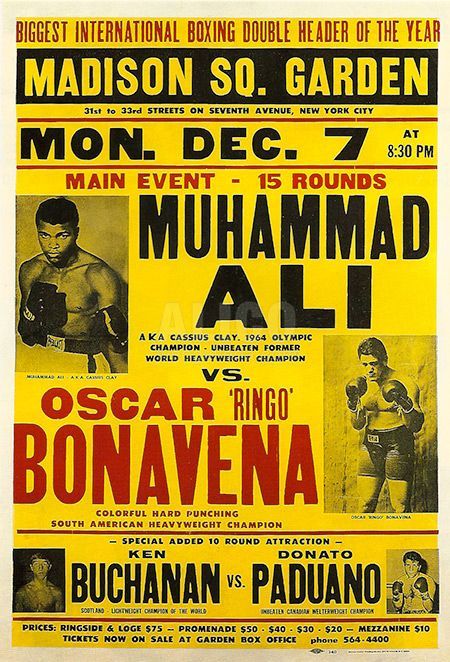

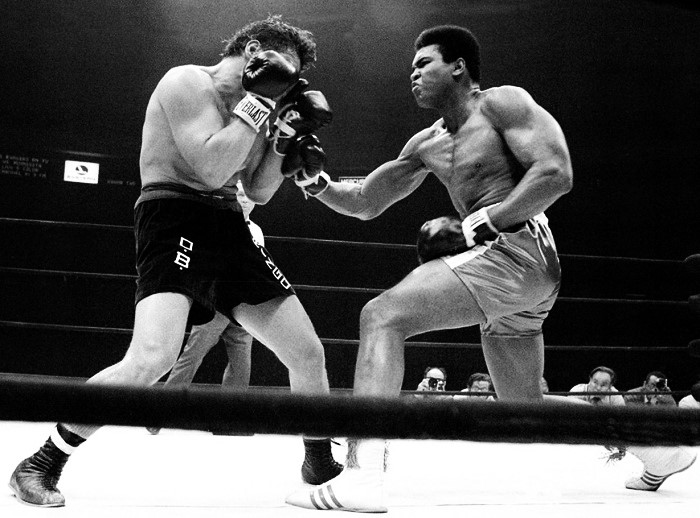

Dec. 7, 1970: Ali vs Bonavena

You can take issue with his politics, label him a braggart and a loudmouth, make an inventory of all the lucky breaks he got, and even insist the Sonny Liston fights were fixed and his wins over Norton, Young and Shavers were gift decisions. But what you can never do is question the competitive spirit and fighting heart of Muhammad Ali. In 1970 there was only one reason for the undefeated former champ to dare to take on iron-tough Oscar Bonavena after just a single fight in almost four years, and that was to prove to the world that he was — despite the many months of inactivity and the widespread recognition of Joe Frazier as boxing’s new heavyweight champ — still the king, still “The Greatest.”

At his peak, before he refused to be drafted into the military and was forced into exile, Ali was a heavyweight boxer of extraordinary quickness and agility, but when he returned to action in 1970, much of that quickness was gone. But his competitive instincts were not the least bit inhibited. Consider that Ali’s very first match after a layoff of more than forty months was against Jerry Quarry, the top contender for the title, a skilled counterpuncher with a deadly left hook. Ali looked sharp in the opening round in Atlanta, but as early as the second the effects of his long absence from the ring surfaced as the pace slowed and Ali’s timing lagged. It may have been fortunate for Ali that Quarry sustained a cut in round three that was so deep the match was immediately halted.

Meanwhile the behind-the-scenes struggle to fully restore Ali’s right to ply his trade continued and indeed a court order had to be secured before “The Louisville Lip” could lace up the gloves and battle Bonavena in New York’s Madison Square Garden, just six weeks after the win over Quarry. Again, there was no urgent reason for Ali to take this fight. He could have bided his time, beat up a soft touch or two to get himself back into peak condition, and let the anticipation build for the huge showdown to come with Joe Frazier.

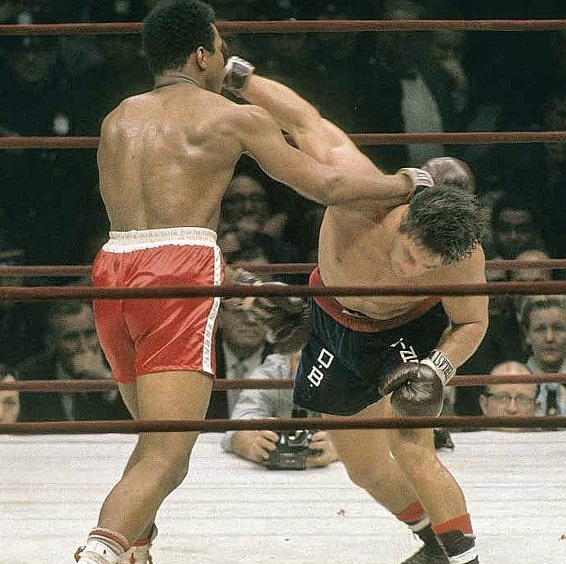

But Ali was a warrior, and no one had given Frazier a tougher battle than Bonavena. And it’s important to remember that for many, Ali was still the true champion. After all, he was still undefeated. Facing anything less than genuine threats, legit top contenders, would have undermined his claim to being the rightful ruler of the heavyweights. Quarry had been, at worst, the number two contender in the world. Bonavena was a few notches lower, but he had given Frazier a pair of tough battles, even knocking Joe down in their first clash in 1966. Ali’s intent was clear: a dominant victory over Bonavena would bolster the argument that he was the true heavyweight king.

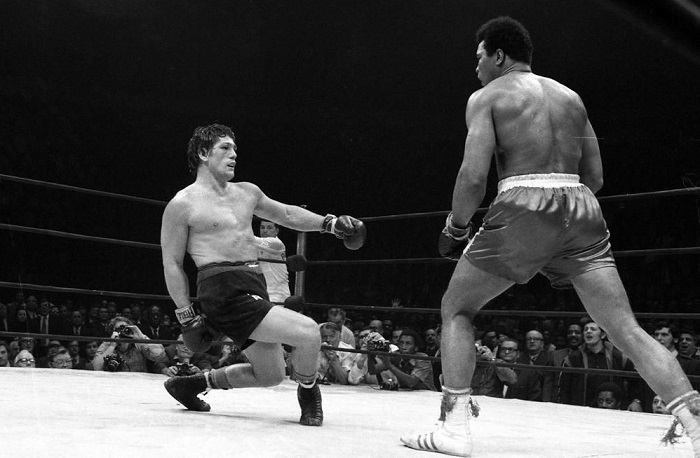

Easier said than done, however. The Argentinian strongman may have been crude, but he was tough and powerful, and completely unintimidated by the boxer he insisted on calling “Clay.” In addition to having given Frazier two tough scraps, he had gone the distance with Jimmy Ellis, beaten two past opponents of Ali in Karl Mildenberger and Zora Folley, and boasted a win over highly regarded Leotis Martin. Simply put, Bonavena was dangerous. Even so, the odds-makers saw him as a six-to-one underdog, but the match had enough intrigue to bring a near sell-out crowd to Madison Square Garden and make the turnstiles sing at some 150 closed-circuit theaters.

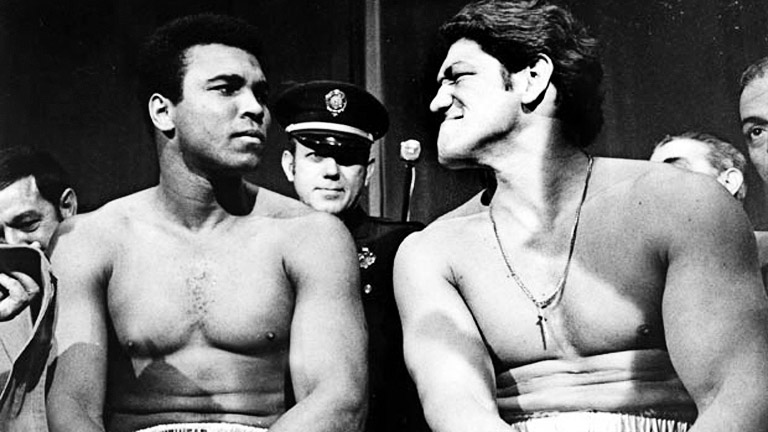

For Bonavena’s part, he wasn’t the least bit impressed by all the hoopla and attention and when the fighters held court with the press, Ali, to his surprise, found himself on the defensive in terms of pre-fight trash talk. The Argentinian mocked him incessantly, calling him a “chicken” for refusing to be drafted, while continually chirping, “Clay! Clay!” None of this was a stretch for Oscar, an insufferably arrogant pugilist who refused to listen to trainers and enjoyed abusing sparring partners. Clearly taken aback, Ali announced he had never wanted so badly to punish an opponent and predicted “Ringo,” who had never been stopped, would succumb by round nine.

But if admirers of “The Louisville Lip” were hoping to once again see the balletic, swiftly moving Ali who had dazzled Sonny Liston and then eight consecutive title challengers before his championship was taken from him, they were no doubt dismayed. This was the new, post-exile version of Ali: markedly slower, heavier on his feet, and, at times, there to be hit. So turgid was his performance in the early going that ringside commentator Howard Cosell could not hide his disappointment. “No sign yet of the Ali skills,” moaned a nostalgic Howard at the end of round one, adding, “the old Ali skills.”

In retrospect, no one should have been surprised this was the case. Three-and-a-half years away from serious training and competition had to take its toll, but if it was easy to visualize the Ali of 1965 bewildering Bonavena with constant movement and blazing speed, the 1970 version allowed for plenty of action, just of a different stripe. Instead of kinetic brilliance, Ali vs Bonavena offered fans an entertaining heavyweight donnybrook, with plenty of rough stuff and both men taking their share of punishment. It defied expectations and it had its lulls, but it certainly was not lacking for action.

It took a couple of rounds for the proceedings to get underway in earnest, but by round three a surprisingly flat-footed Ali had warmed up and was letting his hands go, while Ringo paused just long enough from attempts to nail his opponent in the groin to throw some wild right hands at Ali’s head. The pace quickened in the fourth with both getting home cleaner blows, and for the first time Ali absorbed one of Oscar’s looping rights flush on the chin, a predictable result of Ali’s former cat-like reflexes and unceasing movement being conspicuously absent. That said, Bonavena had yet to win a round.

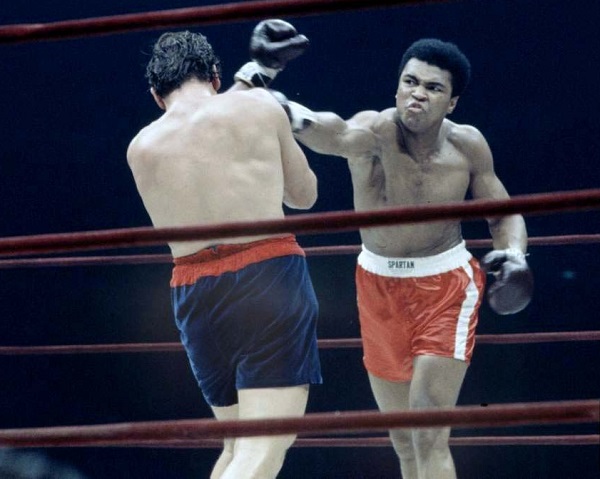

Perhaps aware he was failing to fulfill expectations, in the fifth Ali began to dance, but the footwork of 1970 was a pale imitation of the astonishing moves he had busted in years past, and not swift enough to evade all of Bonavena’s crude attacks. Seemingly bored and looking to spice things up, Muhammad landed a series of desultory body jabs before Oscar made him pay for his nonchalance with a solid left hook to the chops just before the bell.

“Ali simply does not look good,” wailed Cosell.

In round six Muhammad gave the crowd more dancing, albeit in a sluggish style, but this was the first round which Oscar unequivocally won, as he landed virtually all of the meaningful blows. Ali rebounded in the seventh as the fighters traded at close quarters, his left hand snapping Bonavena’s head back repeatedly, but the eighth was grueling warfare, the Argentinian working to get inside as Ali struggled to keep him at bay, timely clinching his chief mode of defense, in addition to his sturdy chin.

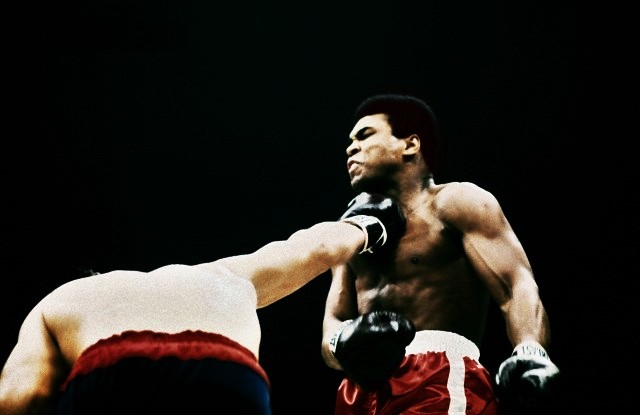

Then came the ninth, the round Ali had promised would be the last, the crowd coming alive, hoping for something remarkable. It began with Ali slipping to the canvas as he threw a left hook, and then the fireworks came, not from Ali, but from “Ringo,” as he landed a series of thudding shots to the head that clearly hurt “The Greatest.” A toe-to-toe slugfest ensued: Bonavena was stunned by a left uppercut that snapped his head back and Ali came on, launching one big shot after another, before the Argentinian then connected with the best punch of the battle thus far, a vicious left hook to the jaw that turned Ali’s legs to jelly. The former dancing master clinched and wrestled to avoid further punishment and was grateful to hear the bell.

Ali would later recall this moment to authors Felix Dennis and Don Atyeo for their 2003 book, Muhammad Ali: The Glory Years: “In that ninth round I got hit by a hook harder than Frazier could ever throw,” recalled Ali. “Numb! Like I was numb all over. Shock and vibrations is all I felt, that’s how I knew I was alive. Even my toes felt the vibrations.”

And yet it was Ali who appeared the fresher man in round ten and he took the round handily, even as Cosell orated unceasingly on his disappointment with his performance. “Where is the old head-slipping of punches? Where is that movement … the rapier-like left jab?” No one, it seemed, was appreciating Ali’s stamina as he continued to set a swift pace in round eleven, nor did he receive credit for his astonishing durability as Bonavena landed some of his heaviest artillery in this round and Ali immediately answered back with his own shots.

In round twelve the pace slowed but there was still no lack of action as the heavyweights stayed largely at ring center and slung leather, Ali connecting with the cleaner blows. By this point it was clear Bonavena needed a knockout to win, but on the rare occasions he could corner his man or get inside, Ali clinched to bring the action to a halt. And while both men were tiring, it was in fact Ali’s punches which had more snap.

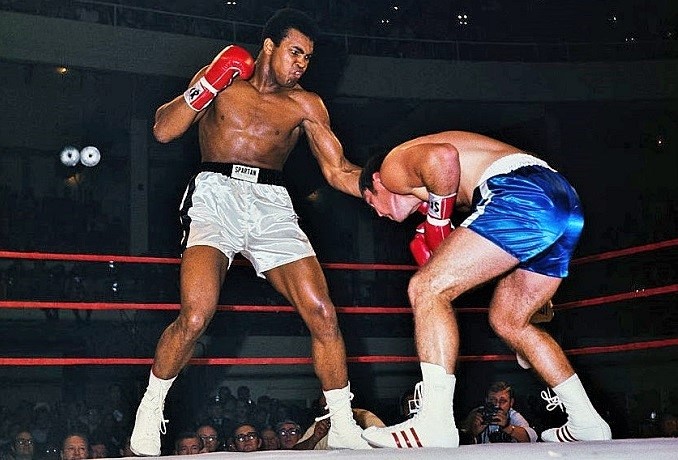

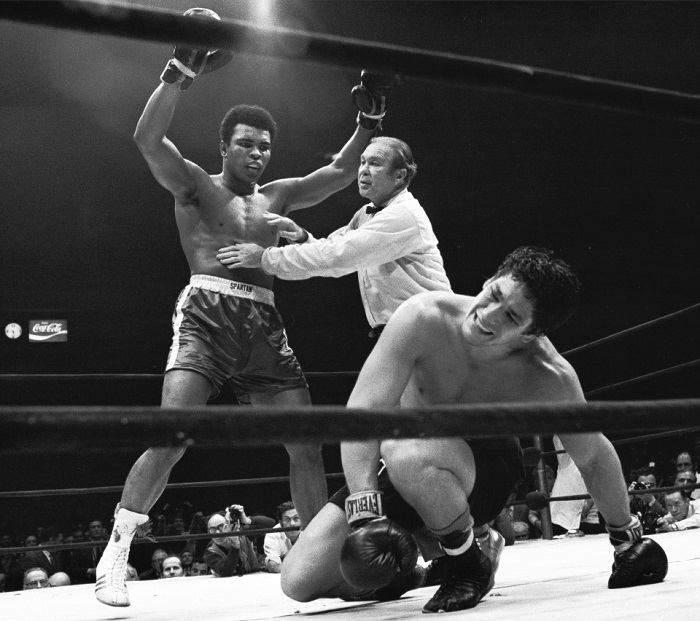

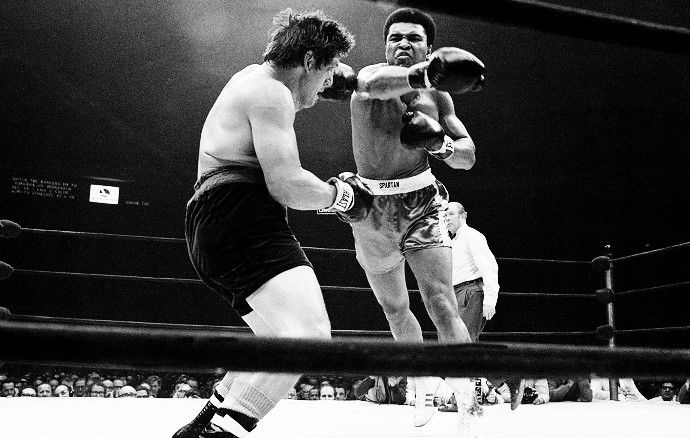

Indeed, Ali’s stamina was something to behold, as he began round fourteen up on his toes and circling the ring. But now the crowd was booing the lack of excitement as the match appeared headed to a lopsided and anti-climactic points win for Ali. But “The Greatest” had saved the best for last. Midway through round fifteen he caught Bonavena coming in with a perfectly timed left hook, flush on the chin, and the Argentinian tumbled to the floor.

Oscar rose but that single blow, with all of Ali’s 212 pounds behind it, had drained what was left of Bonavena’s resolve. No doubt aware the three knockdown rule was in effect, Ali then refused to go to a neutral corner and pounced on a noodle-legged Bonavena the second he arose. Two more knockdowns followed and the match was automatically over, Ali becoming the first, and only, man to ever defeat the incredibly tough Argentinian inside the distance.

It had been a grueling, though largely one-sided battle, and in retrospect all the criticism of Muhammad Ali’s performance was vastly unfair. Bonavena may not have been in Ali’s class in terms of skill, but he remained a dangerous fighter, powerful and tough. For Ali to withstand his challenge and fight on into the championship rounds with as much energy as he did, and at a pace that puts to shame most heavyweight matches of recent vintage, is tribute to his athletic gifts and fighting spirit. Indeed, taking into consideration the long layoff and Bonavena’s proven ruggedness and strength, this has to stand as one of Ali’s most gutsy and impressive performances.

Indeed, it was good enough to prompt the Argentinian to briefly put aside his habitual arrogance to give credit where it was due. “I strong,” he told Ali, “but you stronger. Frazier never win you.” He then announced that his conqueror was definitely “no chicken.”

And if Ali did in fact disappoint those with visions in their head of “The Greatest” resurrecting the extraordinary athletic prowess of his younger, pre-exile self, that disappointment affected not at all the massive, worldwide anticipation for what was to follow. The stage was set; there was no need for further preliminaries. Now it was time for nothing less than the most-watched sporting event in human history, the first clash in a legendary rivalry, that monumental battle between undefeated champions for the undisputed heavyweight crown. Time for Ali vs Frazier, Part One, “The Fight Of The Century.” — Robert Portis

Good article, thanks!

Ali received a lot of criticism, and a number of death threats, for fighting Bonavena fight on 7 December, the anniversary of Pearl Harbour, as if the determination of the fight date were up to the fighters and not the promoter. His refusal to be drafted added fuel to the fire and resulted in many veterans supporting Frazier in the Superfight three months later.