Bad Times for “Bad Intentions”

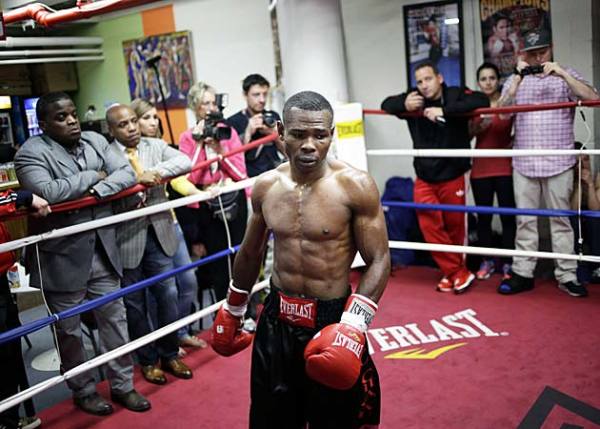

On Wednesday, Arkansas native Jermain “Bad Intentions” Taylor will battle Australia’s Sam Soliman for the IBF world super-middleweight title in Biloxi, Mississippi. It’s rare that anything in boxing can be considered normal, but even by the sport’s bizarre standards this fight will occur in unusual circumstances. Late in August Taylor was arrested for shooting his cousin, Tyrone Hinton, in Taylor’s Maumelle, Arkansas home. Hinton survived and Taylor entered a ‘non-guilty’ plea and is currently out on $25,000 bail. Now almost nine years removed from his two career-defining wins over Bernard Hopkins, the battle-tested, neurologically-damaged fighter enters Wednesday’s bout with graver concerns than boxing.

Once upon a time, Jermain Taylor defeated Bernard Hopkins twice in one year. Given “the Alien’s” continual success, these victories have taken on increased importance. At that time, when Taylor was young, undefeated, and hadn’t yet earned the ignominious reputation of being a boxer who fades late, he was one of the sport’s brightest talents. The handsome pugilist was affable, heavy-handed, and had a novel introductory routine: standing in his corner with one hand raised, he would grind his feet into the canvas like the razorback hog that serves as the emblem for his home state and the University of Arkansas.

After beating Hopkins for a second time, Taylor then outpointed Winky Wright, another probable Hall of Famer, in June of 2006. Two more wins followed before he met Kelly Pavlik in September of 2007 for the fifth defense of his WBC title. Pavlik was a hard-hitting middleweight whose skeletal bone structure hid his power. They waged a brutal war. Taylor floored Pavlik in the second round but the challenger got up and in the wild middle rounds slugged his way back into the fight. In the seventh a sustained attack by Pavlik left Taylor slumped in a corner and forced referee Steve Smoger to end the contest.

The Boxing Writers Association of America named it their ‘Fight of the Year’, but it was a devastating loss for Taylor. He had not only lost his world title but he’d been knocked out, and late, which confirmed suspicions he could not maintain a fast pace in the later going. Taylor had shown this vulnerability twice against Hopkins but still managed to hold on for close decision wins. Pavlik didn’t even give him the opportunity to gas out, as the Ohioan ensured that his hands, and not Taylor’s tired lungs, decided the outcome. They met again the following February in a more tactical contest, and Pavlik won by unanimous decision. Only six months previously Jermain Taylor had been an undefeated middleweight regarded as one of the world’s best, and now he had two losses and no titles. Things did not get easier.

2009 was an especially bad year. In April he was stopped by Carl Froch with fourteen seconds remaining in round twelve. Taylor actually knocked the Englishman down in the third, which was the first time Froch had ever felt the mat as a professional, but “Bad Intentions” couldn’t sustain his momentum. Froch’s spirit proved too much in round twelve when he assaulted the hapless Taylor with a series of concussive punches that rendered Jermain helpless. It was the sort of knockout loss that irreparably damages a fighter, similar to when Meldrick Taylor was stopped by Julio Cesar Chavez with seconds to go in their classic war. To come so far, only to be pounded into submission so close to the end, takes a psychological toll that is not easily surmounted.

In October of that year Taylor traveled to Germany to face Arthur Abraham. Behind on all three scorecards, he was—almost unbelievably—knocked out again with less than fifteen seconds remaining in the final round. This defeat had serious neurological consequences for a man who’d already endured his share of brain pain. Taylor was diagnosed with a subdural hematoma after the fight, a dire prognosis but one not entirely surprising: he had appeared unconscious while falling to the mat after the knockout blow. The pride of Little Rock had now lost four of his last five bouts, and while his prospects of re-emerging as a contender seemed slim, more concerning was the health of his brain, given the spate of wars he’d recently engaged in. It would be 26 months before he fought again.

In spite of this scary brush with permanent disability, Taylor was somehow cleared by doctors to fight again and returned to stop Jessie Nicklow in December of 2011. Subsequent wins over Caleb Truax, Raul Munoz, and Juan Carlos Candelo have perhaps convinced him he is once again a legitimate middleweight threat. None of these men are top fighters, but then again, can that designation be applied to Sam Soliman, Taylor’s opponent on Wednesday? The 40-year-old Australian has won nine of his last ten fights but he also has eleven career losses. The only recent bout he didn’t win came last year against Felix Sturm, after it was revealed that Soliman had traces of the banned substance methylsynephrine in his body.

Most people aren’t taking this match seriously. It pits an old, little-known champion who has tested positive for PED’s against a once-formidable champion who’s endured disturbing events in and out of the ring. If it is interesting at all, it is only in a morbid way—to gauge whether Taylor is physically and mentally equipped to compete. I sincerely hope he is, given what might happen if his head and heart are not in the right place. It is doubtful he should still be boxing, but he likely has no choice. The fight with Soliman was signed before the incident in August and with future legal bills to pay I suspect there aren’t other lucrative occupations he can turn to outside of prizefighting. I am in no position to comment on or assess Taylor’s guilt, but regardless I hope he emerges from this scrap as physically unscathed as possible. An ominous cloud hangs over him. Wednesday’s bout will determine whether or not that cloud darkens.

– Eliott McCormick