Anything Can Happen: Lee Wylie Analyzes “Mayhem”

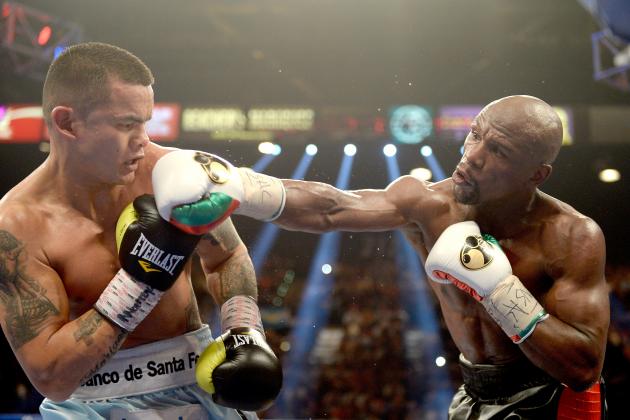

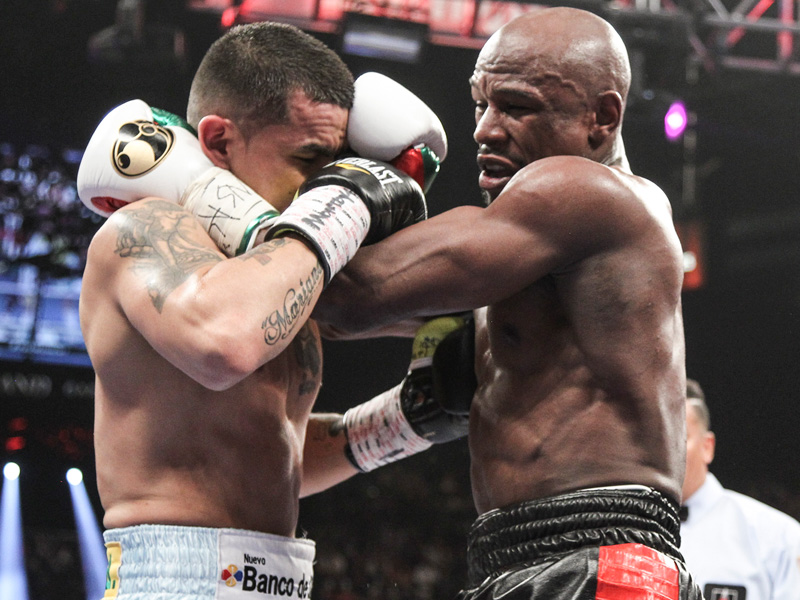

Not since Jose Luis Castillo in 2002 has anyone done enough to truly deserve a second chance against boxing’s consensus best, Floyd Mayweather. But last May Marcos Maidana did more than enough as over 12 action-packed rounds he connected with more clean blows on Mayweather than any previous opponent. Few expected the match to be as competitive and compelling as it was, least of all Mayweather himself. But right from the opening bell, Maidana proved he wasn’t there to simply pick up a pay-cheque: he came forward, forced his man to the ropes, and turned what many thought would be a boxing exhibition into a dogfight.

Not until the bout’s second half did Maidana’s unrelenting pressure ease off just enough for Mayweather to move off the ropes and to the center of the ring where, with more time and space available, he walked Maidana into some well-timed counters and gained control. In the end the champion received the benefit of the doubt on two of the three judges’ scorecards, but it was still nothing like what we have grown accustomed to seeing when Floyd Mayweather fights. For the first time since facing Castillo, the undefeated Mayweather was in a match he could conceivably have lost.

“Everything in boxing is backwards.” – Frank Dunn, Million Dollar Baby.

All told, what we witnessed in the first fight, for the most part anyway, was a “perfect” defensive fighter being outfought and, at times, out-thought by an imperfect offensive fighter. In the eyes of the uninitiated, Maidana’s unsophisticated, crude-looking style should never have bothered the world’s finest technician. But it did.

Why was it, then, that someone like Juan Manuel Marquez, a textbook puncher who throws his combinations with the technical precision and co-ordinated rhythm one expects to see in a truly elite fighter, barely managed to lay a glove on Mayweather, yet Marcos Maidana, who on the surface fights like a barroom brawler, gave Floyd his biggest scare in more than a decade?

To answer that question, let’s ponder Mayweather’s half-guard/crab defensive construct for a moment (often referred to simplistically as a “shoulder roll” defense). By design, it is geared towards rendering textbook combinations ineffective; using the rear hand to catch or block an (orthodox) opponent’s jab or left hook, and a raised lead shoulder to protect the chin from an opponent’s right hand, Mayweather has little problem dealing with the kind of conventional, cadenced attacks (i.e. jab-straight right-left hook) most boxers spend hours in the gym drilling and perfecting.

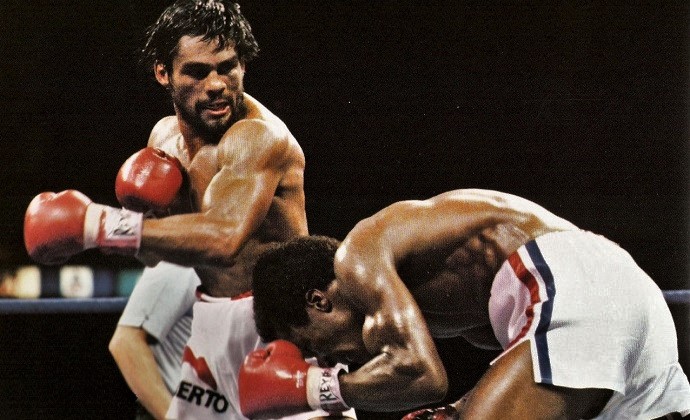

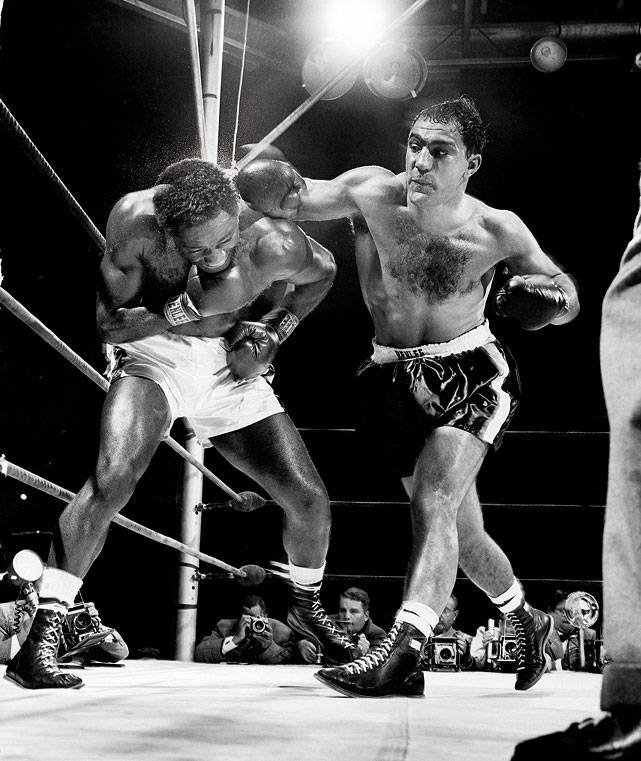

Conversely, along with the deceptive nature of his approach (which we will touch on shortly), Maidana’s awkward-looking, discordant rhythm and unconventional punch trajectories, considered “caveman-ish” in some circles, are precisely what threw Mayweather off his game. Quite simply, it’s difficult to time and counter what cannot be anticipated. And just as was the case with Rocky Marciano when he faced superior technicians like Archie Moore, Ezzard Charles and Jersey Joe Walcott, Maidana proved the anti-technician to Mayweather’s sophisticated technique. Unorthodoxy is a technician’s worst nightmare, and history is replete with instances where fighters like Maidana have turned out to be the stuff of nightmares for boxers like Mayweather.

METHODICAL MADNESS

Essentially a swarmer, Maidana’s ring craft is greatly understated and has improved tenfold under the tutelage of his esteemed trainer, Robert Garcia. Once merely a prototypical blood-and-guts battler, Maidana has a much firmer grasp of some of the more scientific elements of the sport. Nowadays, the rugged Argentine is far more methodical in his approach. In short, he is a tactical, thinking man’s mauler.

For example, Maidana’s high-volume, mauling strategy would never have amounted to anything against Mayweather had he not been able to get himself into position to implement it in the first place. Combining his newly improved jab with subtle feints and level changes as he shuffled forward, Maidana did a superb job of closing the distance and maneuvering Mayweather in such a way as to maximize his strengths while disguising his own weaknesses. Mayweather’s timing and control of distance are usually impeccable and remain among the most cultivated in the modern game, but Maidana’s pressure and deceptive entries made it difficult for Floyd to ascertain his opponent’s intentions and effectively counter them.

The defensive properties now built into Maidana’s offensive dynamics had much to do with this. With improved punch mechanics and head movement, Maidana is no longer the easy target he once was. Even in the center of the ring — unquestionably Mayweather’s domain — there were times when Maidana neutralized Floyd’s considerable hand speed advantage by making him miss and intercepting his attack with his own. Known as simultaneous countering or split-entry attacking, this entails performing an inside or outside slip and simultaneously throwing an accurate punch. It’s a far more efficient tactic than evading an attack and countering afterwards, though it demands precise timing. By rotating his hips forward (right hip forward for a right-handed punch, left hip forward for a left-handed punch) and taking his head offline and away from the center (where most opponents base their attacks), Maidana simultaneously evaded and countered Floyd’s leads with either a jab or right hand.

In short, Maidana’s success against Mayweather was not just about being aggressive and fearless and throwing punches in bunches, but instead involved more craft and technique than most people seem to realize.

MASTERFUL MAYWEATHER

But that said, and despite all of Maidana’s technical improvements, it’s Mayweather who holds the advantage in craft in almost every facet of the game. From a tactical perspective, both offensively and defensively, the erstwhile “Pretty Boy” is about as good as it gets. Without a doubt, he is one of the most intelligent boxers to emerge in the last 40 years or more.

Mayweather’s ability to draw attacks from his opponents, either by creating tempting targets or by positioning himself in such a way that his adversary has little choice but to initiate in the manner Floyd desires, marks him out as one of the best counter-fighters to ever set foot inside a boxing ring. What may look like otherworldly speed and reflexes, is more often simply foreknowledge of what an opponent will do in a given situation. Simply put, it’s a hell of a lot easier to anticipate something when you know it’s coming. Being able to influence an opponent’s decision-making process and funnel their offensive options in this way is a rarefied skill few boxers ever acquire. This is precisely why it is never a good idea to give Floyd time and space in which to think. Afford him these luxuries, and he will systematically pick you apart.

Another cornerstone of Mayweather’s game, and one which continues to be neglected by many fighters and trainers, is the body jab. Floyd may not target the body often with hooks and uppercuts, but he frequently does so with his jab in order to create openings and lure an opponent into traps. Once a boxer begins adjusting their guard to compensate, Floyd will suddenly change the line of his attack and ruthlessly take advantage of the newly created opening.

Mayweather’s greatest fighting attribute, however, could well be his conceptual understanding of time. Not so much as in being in the right place at the right time—though, through a mastery of positioning and distancing he has that underlying principle down pat too—but more a knowing of where and when to insert his chosen techniques within a fighting context: an appreciation of before, during and after as it relates to boxing.

In terms of defense, where most fighters simply wait and react, executing a defensive technique (block, parry, slip, etc.) after the opponent has already started to throw a punch, Mayweather understands that techniques can be used at any time. For example, after landing his straight right, Floyd will proactively duck underneath and weave out to his right in anticipation of his opponent’s likely left hook counter—a defensive move executed immediately after Floyd’s own offense but before the opponent has initiated his own. It’s preemptive measures like this which allow Mayweather to remain one step ahead of his opponents at all times and which force them to react to whatever he is doing instead of the other way around.

STRATEGIC AND TACTICAL VARIABLES

Nothing much has really changed from the first fight. While there are some slight tactical adjustments both boxers could make, everything else is more or less the same with regards to strengths and weaknesses and strategy. With this in mind, let’s go over some tactical considerations, analyzing what both men did in the first match, and the ways in which they could improve this time around.

MAIDANA:

For Maidana, it’s again about applying constant, educated pressure and denying Mayweather his preferred working space. Against the ropes, Maidana did an excellent job of cutting off Mayweather’s punching room by placing his forehead on Floyd’s chest, thereby squaring him up and restricting his ability to duck and roll punches. Put simply, whenever Mayweather was near the ropes, Maidana was able to block off his escape routes and create a bigger, more stationary target for himself.

Along with his jab and constant change in elevation as he closed the distance, Maidana’s most effective weapon was his looping overhand right, which often bypassed Floyd’s defending lead shoulder and landed on the top of the head. Maidana found a home for it almost every time he got himself into position to throw it. This time, Maidana would be well-served to mix up his looping punches with short, snappy jolts to the body during any in-fighting. This will not only force Mayweather to bring down his guard and give Maidana’s heavy artillery a greater chance of landing up top, but it should also eat away at Floyd’s stamina and limit his mobility.

On the inside, Maidana could also profit from varying his alignment in relation to Mayweather, either to the outside or inside of his guard, in order to secure more advantageous angles and to keep Mayweather from lining him up. In addition, whenever the champion is against the ropes, Maidana could introduce a new (though slightly questionable) tactic and with one hand pin Mayweather’s lead arm, which Floyd often holds very close to his body, and then cut loose with his free hand. However, whether or not referee Kenny Bayless will permit Maidana to get a little dirty on the inside, as he was allowed to last time, is an open question. By the same token, it will be interesting to see if Mayweather, who is no stranger to roughhousing tactics at close quarters himself, will be allowed to do the same.

Mayweather does a tremendous job of protecting the center of his body by blading his stance and closing off his main targets behind his lead shoulder, but no single guard or stance is impenetrable, and that includes the champion’s signature half-guard/crab position. Maidana should attack what is presented to him and slash Floyd’s left flank with Ray Robinson-style right hooks. Such an attack could force Floyd to surrender further openings elsewhere, especially if he squares up to compensate.

To his credit, Maidana seems to understand better than most that when it comes to sharing a ring with Mayweather, everything becomes a viable target. In their first encounter, Maidana wasn’t afraid to hit what was available and didn’t make the same mistake others did by sitting back and waiting for a perfect opening. Against a defensive savant like Floyd, there are none. Thus, even more than he did last time, Maidana should hit Mayweather on the arms, shoulders, hips―basically anything Floyd gives him—in order to sustain his attack and force openings.

But to penetrate the champion’s defensive infrastructure, Maidana must first throw off Mayweather’s defensive timing. Feints and false attacks, along with variations in rhythm and tempo, are the best way of accomplishing this. If Maidana is to have any chance of breaking down Mayweather’s defense, attacking indirectly, and between “beats” as Mayweather executes his defensive motions, is of the utmost importance.

Maidana’s level changes worked extremely well for him last time and remain indispensable as far as closing the distance is concerned. By getting low and making himself a smaller, more elusive target while also forcing Mayweather to aim lower than usual, the challenger created numerous opportunities for himself. In fact, if one were to draw a direct comparison between the tactics employed by Maidana and those of Castillo, the constant change in elevation as they cut off the ring would be the most obvious commonality. Level changes are not only a great way of closing the gap and disguising one’s intentions, but they also aid in reducing the opponent’s punch output by making them wary of letting their hands go for fear of exposing themselves to counters. The lower Mayweather’s punch output, the more chance Maidana will have to win rounds.

The challenger’s jab was an important factor in the first clash and it must be again if Maidana is to win. That said, it’s fairly difficult to hit Floyd clean in the face. Thus, it’s a good idea to target his chest and lead shoulder when throwing the jab. In addition, it would be wise to get behind the lead shoulder and dip to the right slightly when stepping in with the jab so it’s more difficult for Floyd to find him with straight counters. Doubling up on the jab (again to the chest and lead shoulder) will also help to disturb Floyd’s balance and prevent counters coming back.

Using the jab to establish a pattern of attacking one target for a period of time before suddenly switching to a different target is an excellent tactic and one which Maidana should definitely employ against Mayweather. This is something he pulled off extraordinarily well against Adrien Broner. He conditioned “The Problem” to reach low to parry a body jab before suddenly turning it into a left hook and nailing the brash American flush.

Throughout the second half of the contest, there were too many instances when, instead of getting himself into position first and then letting his hands go, Maidana swung wildly on the way in and allowed his center of gravity to overtake his base support. Thus, Maidana unintentionally threw himself off balance by allowing his torso to overtake his lead foot. The challenger cannot afford to make this mistake again. If he does, Maidana will make it easy for Floyd to snapback/pivot and nail him with counters while his position is compromised. Nobody in their right mind would suggest that Mayweather’s punching power is on par with that of Sam Langford or Stanley Ketchel, but should Maidana get a little overzealous in his forward pursuit, Floyd certainly hits with enough precision and vigour to make him pay.

As we’ve already discussed, Mayweather is more defensively responsible than most, but he is no different from any other fighter who has ever laced up a pair in that he’s at his most vulnerable while he is punching. Whether he’s employing it as a “pawing” probe to gauge distance and create openings, or as a defensive post to “stiff-arm” and return to safety, Floyd’s lead hand is tremendously active and is by far his most frequently used offensive/defensive weapon. Therefore, Maidana should act accordingly and target the resulting opening by slipping inside Mayweather’s outstretched lead and throwing his overhand right over the top.

But more than anything else, Maidana cannot afford to give Mayweather much space and time in which to think. Waiting and trying to react to Mayweather is an exercise in futility. He’s simply too fast. For that reason, it’s important for Maidana to always be first and to keep the pressure on. In fact, whoever got off first last time stole the initiative and governed most exchanges.

MAYWEATHER:

For Mayweather, it’s relatively straight forward: in order to nullify Maidana’s strengths and take advantage of his weaknesses, he has to prevent the challenger from setting up his offense and keep things in the center of the ring as much as possible.

Last time, in response to Maidana’s level changes, Floyd generally moved straight back which led to him being corralled to the ropes and forced to exchange. This time, Floyd would be well-served to focus more on positioning, using both linear and lateral footwork to increase the distance and keep Maidana turning, thus preventing him from getting set to hit. Of course, this comes with a caveat: potentially, Mayweather could end up inadvertently maneuvering himself into the path of one of Maidana’s circular blows, namely an overhand right or left hook, so he must be careful when circling out of range.

In the second half of the fight, Mayweather’s check hook was probably his most resourceful weapon and it has the potential to be so again. By throwing the left hook and then angling off, Mayweather constantly offset Maidana’s alignment and denied him entry.

Mayweather must dictate the pace of the bout. He has to try and slow Maidana down so that his shots aren’t rushed or forced in any way. One way is to target Maidana’s body whenever it’s safe to do so. Another is to disrupt his offensive rhythm by controlling him in the clinches, either by getting off first and securing overhooks, or by seizing control of his head, which will be attainable as Maidana will again be coming in low from the outside. This is something we saw in the second Ali-Frazier fight and, more recently, in the Kell Brook-Shawn Porter fight. In fact, Devon Alexander also had a lot of success using similar punch-and-grab, smothering tactics against Maidana when they fought.

If Mayweather is pushed back to the ropes, or even goes there voluntarily to preserve energy, he needs to maintain the integrity of his stance as much as possible. This means getting his trailing foot out from under him and employing his lead arm as a barrier to prevent Maidana from getting to his chest and squaring him up. Mayweather also likes using his lead forearm as a wedge underneath the opponent’s chin to pry open their guard and his lead shoulder to bump and create space for tight counters on the inside. If Maidana continues to come in low, the rear uppercut, either as a lead or as a counter, could be an invaluable weapon for Mayweather.

CONCLUSION

In truth, I have no idea what will happen on Saturday. Nobody does. That’s because anything can happen in what are the chaotic, constantly changing dynamics of a boxing contest.

We all know Mayweather is a masterful tactician—arguably the sport’s finest—and is well-versed in making the necessary adjustments to meet the task at hand. However, probably more than any tactical adjustment or technical nuance, it was Floyd’s superior conditioning that allowed him to weather the early storm and turn the tide last time, for whenever Maidana’s gas tank permitted, there was seemingly very little the American slickster could do to hold the Argentine mauler off. Maidana’s pressure wasn’t always effective, but it allowed him to steal the initiative and kept Mayweather from doing what he wanted.

Evidently, it remains to be seen whether or not Maidana can consistently bridge the gap and keep it that way for 12 rounds—Maidana’s endurance was arguably the biggest factor in the first fight and it could be again on Saturday night.

So, with improved stamina and some minor technical refinement, who knows, maybe Maidana can go one better and become the man to hand Mayweather his first official loss as a professional prizefighter. Or perhaps Mayweather is right after all, and it is just simply a matter of him this time choosing to box on his terms in order to kill any drama and get the job done.

Needless to say, all questions will be answered Saturday.