Question and Answer With Lee Wylie (No. 2)

Suffering from uncertainty about your lead shoulder feint? Having trouble with your distance management or footwork? Are concerns about how best to parry a right lead keeping you up at night? Well, fear not: Lee Wylie is here to help. Just send in your questions on any strategic or tactical problems, and Lee will take care of the rest. Email your questions to thefightcity@gmail.com and Lee will respond as quickly as possible.

Dear Lee Wylie,

I’ve been working on training to fight as the orthodox aggressor. However, I have a few questions. How would you recommend dealing with an opponent who constantly feints? It’s hard to know when to be aggressive and in what way when it’s so difficult to tell what the opponent is going to do. Also, what do you think is the best way to deal with a check left hook? Feint and then come in? Weave under it? Throw the cross at the same time? I also wonder how to cut off the ring against an opponent who is able to change directions extremely quickly. Finally, what fighters would you recommend studying for fighting with intelligent aggression? The current guys who come to mind are Golovkin, Kovalev, and Lomachenko (especially).

From, Curious Boxing Fan

P.S. Can I get your predictions on the following fights: 1. Matthysse vs Provodnikov 2. Garcia vs Peterson 3. Lee vs Quillin 4. Crawford vs Soto/Herrera 5. Jhonny Gonzalez vs Gary Russell 6. Algieri vs Cage.

Dear Curious Boxing Fan,

In truth, there are no hard and fast rules when it comes to dealing with feints. How you choose to respond to them is purely circumstantial and a lot depends on the characteristics, temperament and goals of both you and your opponent.

Feinting is a multi-purpose tactic, and not all boxers share the same reasoning for using them. For example, some boxers use feints to actively create openings, tensing or shifting their body in a threatening manner so as to elicit a reaction and open up a target. Others feint merely to check the opponent’s tendencies and to make a note of when and from where is the most opportune moment to attack. And finally, in some cases (which probably concerns you the most) a boxer may feint simply to disrupt his opponents’ rhythm and stunt their forward momentum.

Against inquisitive counter-punchers who regularly feint in an attempt to get a read on the opposition, it’s best to try and provide them with as much false information as possible. In some respects, feinting is a lot like posing a question: “What’s my opponent’s response to a half-extended jab or a subtle step forward with my front foot?” Or, “What does my opponent do with his guard if I quickly rotate my hips and tilt my rear shoulder towards him?”

Under these circumstances, a boxer who is naturally patient and possesses an analytical mind could potentially pick up on his opponent’s “questioning” and deliberately set traps. For example, let’s say your opponent throws lead shoulder feints and each time you respond by reaching out to parry what you perceive to be a jab with your rear hand. If the opponent has identified your “tendency,” he may now feint a jab for a third time and immediately follow up with a hook aimed around your extended rear hand where he’s anticipating you will be open. However, instead of parrying for a third time, you move your rear hand close to the side of your head, allowing you to block your opponent’s forthcoming left hook and return fire with a left hook of your own. For a better understanding of setting traps using feints and false threats, I recommend watching Ray Robinson’s knockout of Gene Fullmer. In fact, I made a video about it.

https://youtu.be/U7Hi3tnGW7I

One final note on feints: Rather ironically, pressure fighters tend to react more passively to feints, either by momentarily freezing or becoming more cautious. Counter-punchers, on the other hand, tend to become more aggressive as they seek to take advantage of apparent openings in their opponent’s defense.

Though there are some slight variations regarding footwork (Floyd Mayweather immediately comes to mind), a “check” hook is a lead hook thrown simultaneously with a pivot off the attack line (clockwise for an orthodox boxer). And the best solution for a check hook, or any other hook for that matter, is not to put yourself in a vulnerable position to be nailed with one in the first place. Fundamentally, boxers who overcommit with their attacks, resulting in their center of gravity tilting too far forward, often find themselves susceptible to hooks. You needn’t look further than Ricky Hatton and Vic Darchinyan literally running into the respective left hooks of Floyd Mayweather and Nonito Donaire for evidence.

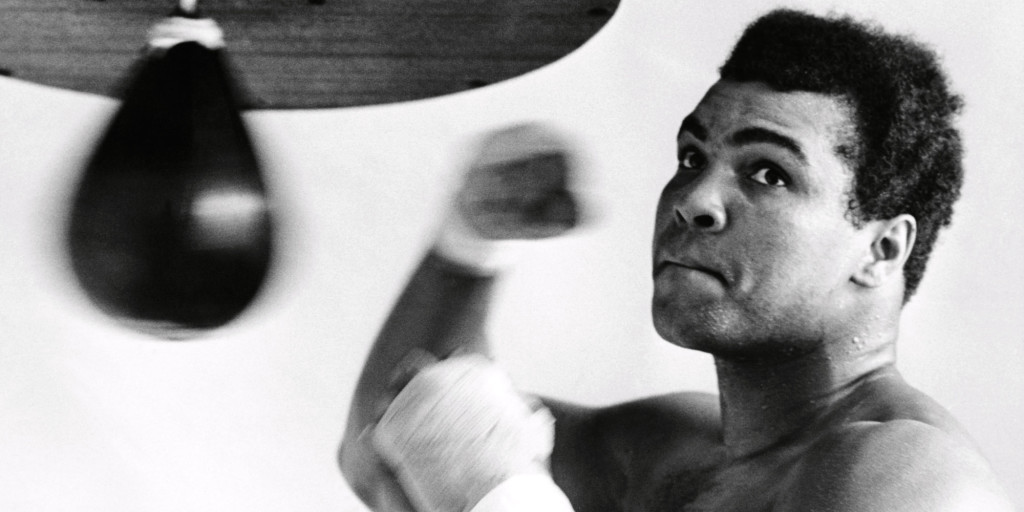

Failing that, you should either catch it on the outside of your rear glove or forearm, or duck underneath the blow and weave out to the side from where it came. Doing the latter also puts you in a relatively safe position from which to launch a counter. Although rule-breakers like Muhammad Ali, Wilfred Benitez and Roy Jones Jr. did it often, I certainly wouldn’t recommend pulling straight back from hooks as very few boxers have been blessed with the same reflexes and defensive instincts as those three. It’s definitely much safer to either block or evade the attack all together by, as boxing coach Don Familton liked to say, taking the train off the tracks. It is equally unwise to try and parry or slip hooks.

If your opponent tips his hand before throwing his hook, such as by allowing it to stray outside his frame or by pulling it back prior to its delivery, you can intercept it with a rear straight. However, if both fighters have their same foot forward, a lead hook is a natural counter for any rear-handed attack, especially straights and uppercuts thrown from too far out, so special care is needed. Precise timing and good positional awareness are of the utmost importance here.

Furthermore, when you look to counter a hook, either preemptively before or reactively after, it’s absolutely imperative that you safeguard with your non-throwing hand and take your head offline. Whenever you see two boxers throwing hooks in unison, usually, though not always, it’s the boxer who drops his non-throwing hand and leaves his head centered who comes off worse. So, despite the old axiom that states one should never hook with a hooker, you can have success by countering your opponent’s hook with a hook of your own, provided you’re defensively responsible when throwing it.

As far as cutting off the ring is concerned, it’s vitally important that you don’t just follow your opponent around the ring, linearly retracing his footsteps so to speak. Rather, you should be combining linear movement with both lateral and diagonal movement in an attempt to block off his escape routes so you can eventually get close to him and keep him contained.

Here’s a checklist of things to consider when cutting off the ring:

Always try and “meet” your opponent by intercepting his movement. Move towards where you think he will be, rather than where he is.

Adopting a slightly more horizontal stance than usual generally provides a boxer with more control over his opponents, allowing him to better influence their movement with arcing blows from either hand. Not too long ago Austin Trout inadvertently turned himself into a one-armed fighter by blading his stance too much against Erislandy Lara. Consequently, the task of funneling the Cuban’s movement became a nigh-on impossible one for the American.

Never lunge with your punches. Doing so makes it easy for the opponent to redirect his movement while you are busy recovering your balance. Likewise, don’t get too close to your opponent in the center of the ring as this makes it easy for him to angle off, forcing you to start the pursuit all over. Rather, work your way forward behind the jab and wait until you have corralled him into a weak area such as against the ropes or in the corners before looking to get inside.

Once you have the opponent contained, maximum effort must be expended in working the body, thereby stealing from him the stamina needed to move effectively. Saul “Canelo” Alvarez did this masterfully against the fleet-footed Erislandy Lara last year.

Your opponent will no longer be able to control the bout if he no longer feels in control. Therefore, make him feel like he’s being hunted. Influence his decision making and force him to rush his punches. Instill in him a sense of anxiety.

The names you mentioned — Golovkin, Kovalev and Lomachenko — are fine choices as intelligent aggressors. All three fit the criteria perfectly.

Allow me to add a few more, past and present:

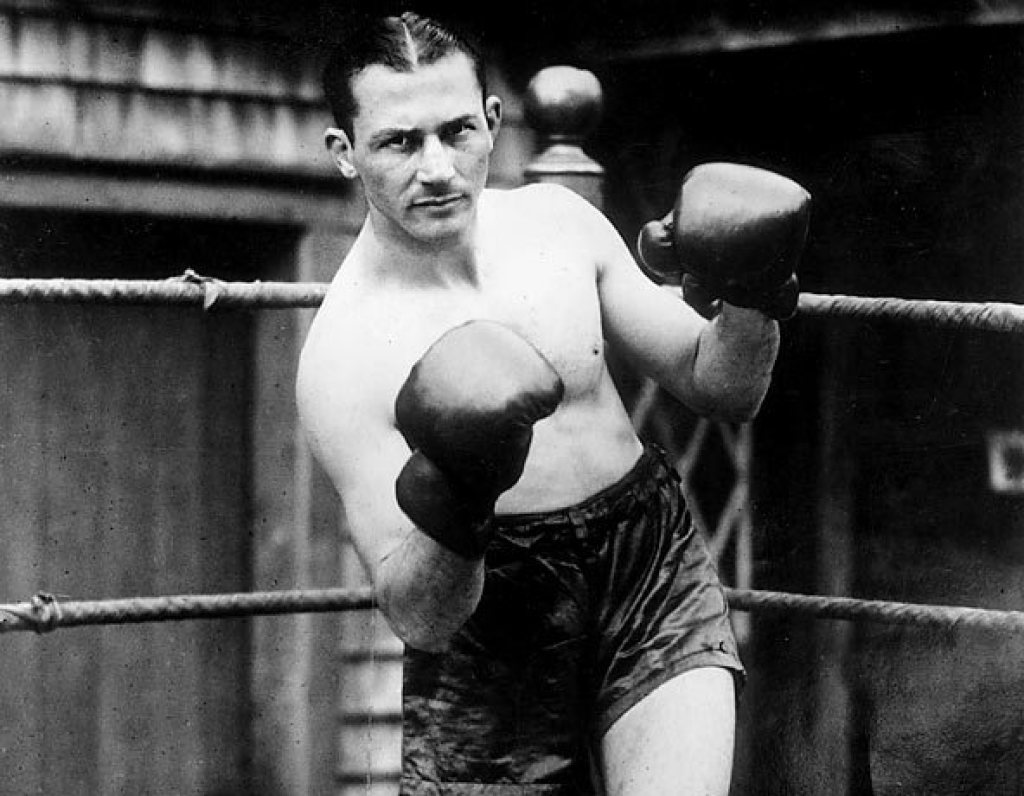

Jose Napoles and Joe Louis: From a technical perspective, their footwork may be without equal. Few have been better at applying pressure whilst remaining balanced, and in position to effectively evade and counter.

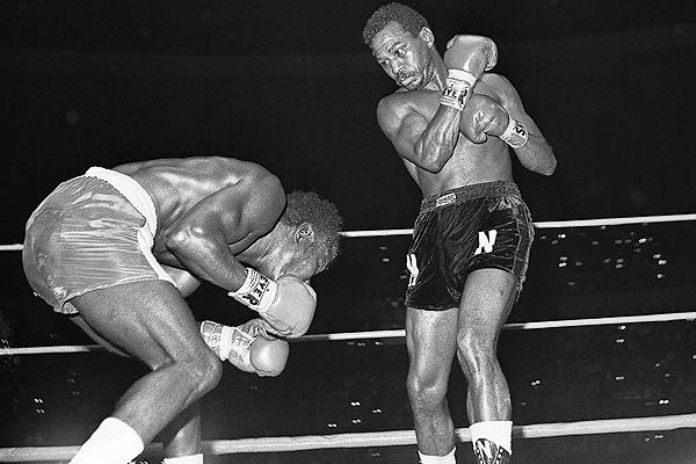

Roberto Duran and Mike McCallum: These guys were just about as versatile as it gets, but I’ve grouped them together here because I’d like you to focus on their proactive upper-body movement. Both were exquisite when it came to transitioning between offense and defense by incorporating ducks and weaves (whether the opponent was returning fire or not) into their combinations. Must see fights are Duran’s with De Jesus (third fight) and Leonard (first fight), and McCallum’s with Michael Watson and Julian Jackson (a fine representation of neutralizing punching power by killing leverage in close).

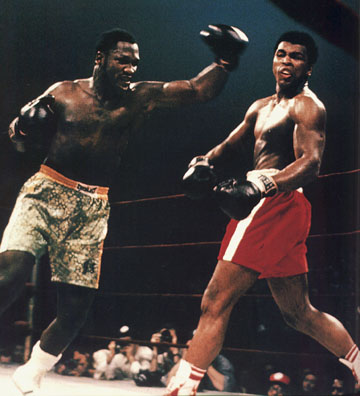

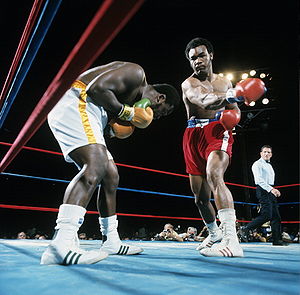

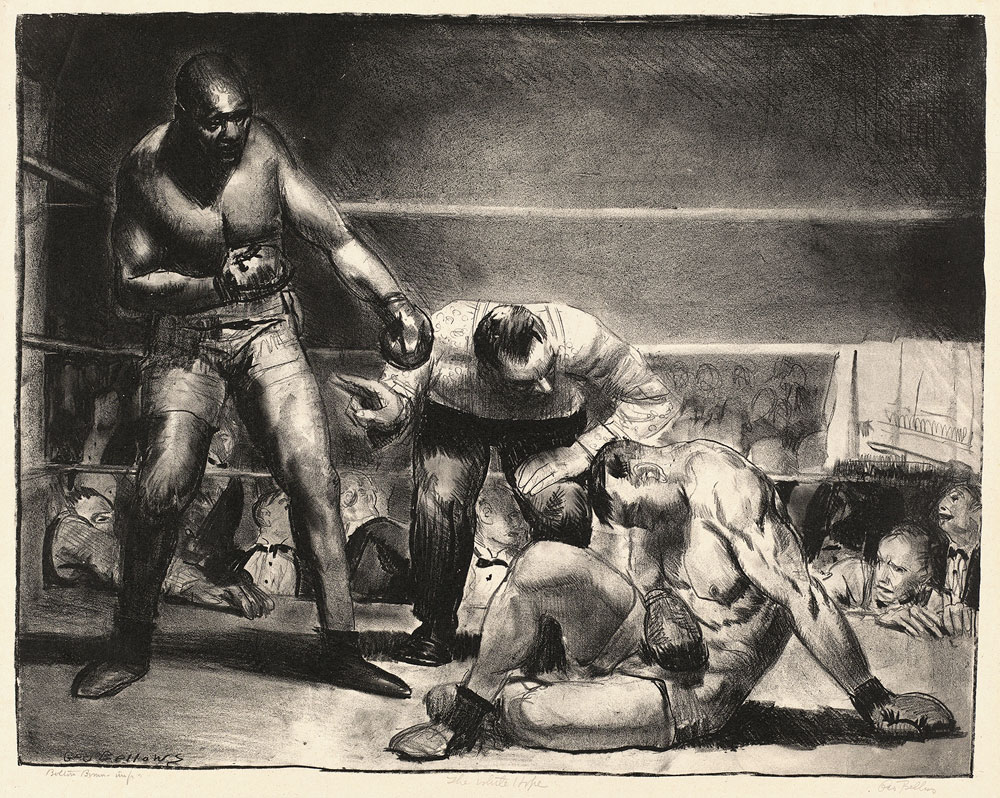

George Foreman and Julio Cesar Chavez: These two are arguably the best ever at minimizing ring space. Like his trainer and past master Sandy Saddler, Foreman often cut the ring off with his rear hand extended, ready to stuff his opponent’s jab at the point of origin. Conversely, Chavez was superb at evading his opponent’s jab by changing the height of his stance and shifting his upper-body from left to right as he moved forward. Take a look at Foreman’s fights with Ken Norton, Bob Hazelton and Gregorio Peralta, and Chavez’s with Edwin Rosario, Hector Camacho and Meldrick Taylor. You’ll also see Chavez slowly grinding Taylor down with a steady body attack.

Manny Pacquiao, Salvador Sanchez and a young Mike Tyson: Along with Duran and McCallum, these guys are the epitome of aggressive counter-fighting. I recommend watching Pacquiao’s fights against De La Hoya, Hatton and Margarito and Sanchez’s against Wilfredo Gomez, Danny Lopez and Juan Laporte, along with some of Tyson’s early fights against Eddie Richardson, Steve Zouski and Reggie Cross (some sublime head movement in that one).

As for the predictions:

I tend to always lean towards the superior technician. Matthysse is technically superior, but I don’t know if he is good enough a technician to make this anything but a war of attrition. That being the case, then, I’ll go with Provodnikov, a fighter who has shown a seemingly unbreakable will.

Peterson’s aggression and high volume attack (though he doesn’t always fight this way) could definitely make things awkward for Garcia. That being said, Garcia has excellent timing and I think he may consistently catch Peterson coming in with significant shots and could potentially stop him.

For my money, Crawford is among the best boxers in the world at any weight. And I can’t see him losing until he starts facing the upper-echelon at 147 pounds.

I do like Quillin in this one, but Lee’s right hook continues to make a fool out of the naysayers. Andy Lee is a fine example of how punching power is contingent on timing, distance, leverage and balance, and not on muscle mass.

Gary Russel Jr. remains a very good fighter, and has only ever lost to an exceptional one in Lomachenko. I think he outboxes Gonzalez when they meet.

I’ll have to get back to you on Algieri vs “the cage” 😉

Good luck!

Thanks for all that Mr.Wylie. I just discovered these question and answer sections, I am really enjoying them.

I reckon feinting is a bit of an semi-instinctive art form and less of a teachable science, that’s why I think it’s so hard to actually master it from a purely cerebral position especially if you can’t get the feel for it naturally. That is what I reckon anyway.