From Managua to Manhattan

Once Floyd Mayweather decided to ‘retire’ this September and retreat further into his sealed bubble of self-exaltation, Nicaragua’s Roman ‘Chocolatito’ Gonzalez gained widespread recognition as the world’s best boxer, pound for pound. On Saturday night Gonzalez makes his first appearance as the sport’s premiere talent when he duels Brian Viloria on the Golovkin vs Lemieux undercard. His journey from Managua to Manhattan has been dramatic, but will his reign be as impactful as his predecessor’s?

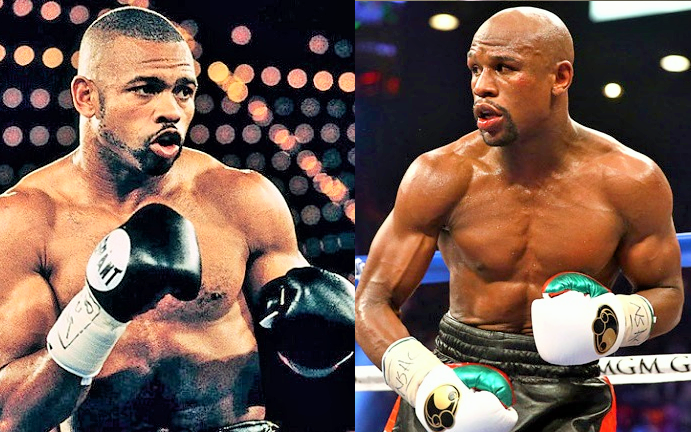

In ways stylistic and spiritual, Chocolatito is Mayweather’s antithesis. If Floyd was brash, vulgar and coldly brilliant, equally obnoxious and insecure, jaded in place of genial, a performer who evinced the laudable traits in the ring that he never showed in public, ‘Chocolatito’ is his opposite: humble, deferential, unburdened by personal ugliness, predatory rather than restrained between the ropes, a fighter who takes chances in his quest to destroy. In this sense, Gonzalez represents change for a sport in need of transformation, regardless of one’s feelings towards Floyd’s remarkable run.

But, his electrifying talent aside, how big can ‘Chocolatito’ be? Will the weight class in which he fights work against him?

In addition to being, for so long, the pound-for-pound Leviathan, Floyd was also boxing’s most popular act. These titles are not synonymous. Mayweather became a superstar through clever marketing, calculated matchmaking, and his own patent exceptionalism. He also fought at welterweight and junior middleweight, divisions home to much other bankable talent. Fans were intimately familiar with his best opponents, whether Oscar De La Hoya, Shane Mosley, Ricky Hatton, Miguel Cotto, or most recently, Manny Pacquiao. In other words, the circumstances were germane for Mayweather’s popularization.

In contrast, Gonzalez fights at flyweight, a division that lacks mass appeal. Despite the considerable talent at 112 lbs, flyweights receive less high profile television exposure than do their larger peers. It is also, perhaps, a matter of demographics. The last American to hold a major title in this division is Brian Viloria, Gonzalez’s capable opponent this weekend. Prior to Viloria, it was Mark Johnson, who vacated his IBF belt in 1999. (Nonito Donaire, who was born in The Philippines but raised in the United States, held the IBF title until 2009.). But even if flyweight was dominated by Americans, my sense is that, in a sport that rewards talent and size inversely, diminutive men work with a handicap.

Perhaps this is a useless meditation. By asking what ‘Chocolatito’ may become, of whether his fame might one day catch up to his accomplishments, he is abstracted from his actual talent, about which there are few questions. Gonzalez earned his place on this card because Golovkin’s promoter wanted to duplicate the success of GGG’s knockout win over Willie Monroe this summer in California; on that undercard, ‘Chocolatito’ took advantage of his HBO debut by notching a thrilling blitzkrieg of veteran Edgar Sosa. Golovkin and Gonzalez are a formidable television duo, and if both continue to appear on the same cards together, chopping through rivals as machetes do jungle foliage, you can bet Max Kellerman will retain his customary smirk in perpetuity.

His brilliance alone will popularize him. Unlike Mayweather, Gonzalez doesn’t need controversy to get over with fans. His performance versus Sosa invigorated The Forum in a rare way: they roared every time one of his sweeping, brilliantly-timed attacks found its mark, and he rewarded their cheers by following up with another salvo. It took only two rounds for the fighter and his fans, each spurring the other on, to coalesce in violent harmony.

This kind of spectacle, where action and excitement escalate in concert, where fans feel as though they’re marching alongside the conquistador, and where victory seems preordained, is one begot only by the greatest fighters, because their sheer talent makes victory seem inexorable. It was a sensational display, regardless of Sosa’s age, and somewhat reminiscent of a young Manny Pacquiao, who stampeded across the lower weight divisions with the same assertiveness. Punches in bunches, carefully placed, which first subdue, then overwhelm, and ultimately destroy an opponent. It is a style that sells.

Can ‘Chocolatito’ go on to become a huge attraction and the sport’s biggest draw? It’s uncertain whether this is even his ambition. He seems hell bent on realizing his potential as a boxer, rather than maximizing his potential as an earner. Is he naïve? Will his earnestness be served a cynical dose of reality? Does this fresh attitude represent real change in a sport where caution is commonplace when fighters plot their careers? To the last question, probably not. Boxers tied to conservative management will continue on their way; if they’re rewarded so handsomely for their trepidation, there’s no reason to deviate. ‘Chocolatito’ is not so much a threat to the status quo as he is evidence of a fresh alternative.

What will become of Gonzalez hinges largely on whether he thrives in the spotlight. That, too, remains to be seen. But for now, he has at least arrived, and rather than question what might become of him, perhaps it’s more important to celebrate what lies ahead: the opportunity to witness the ascent of a generational talent, who at least appears to embody the very traits critics have accused Floyd of lacking. We may have a new master on our hands, one who delivers the very thrills which make boxing –at its height, a tempest of matchless excitement and devastating grace – the most dramatic performance art which has ever existed.

— Eliott McCormick

Thank you, truly, for the amount of effort you carefully put into this website, for it is a real little chest of treasure for any boxing fan.

Hi Roko and thanks for your generous comment. We do our best; keep coming back!