Fight Report: Berchelt vs Valdez

The Event

There’s something cartoon-like about watching certain feats of human strength or endurance. Sitting on your couch, you exclaim, “Did you see that?” when you know they did. The honest among us will even admit to saying that to the screen itself when watching alone. In boxing, such moments are inspired by battles which play out like Tom and Jerry cartoons. There’s Jerry, hitting Tom with a frying pan, but moments later Tom is squeezing the life out of Jerry. Frame by frame the pattern builds until the finale, where both protagonists inexplicably remain standing despite exchanging ordnance so thunderous you know just one of those blows would usher you to the canvas in short order. Such toe-to-toe, back-and-forth tilts are usually sure-fire contenders for the Fight Of The Year, and many predicted that Berchelt vs Valdez would live up to such expectations last night.

After Berchelt tested positive for Covid-19 in December the scheduled showdown was pushed to February 20th. And in the weeks leading up to last night, the boxing world again spun into a frenzy, breathlessly indulging in every available stereotype about blood-and-guts style Mexican fighters, hyping the coming clash between “proud Mexican warriors,” and even promising the sweetest of prizes for the sport of boxing: a fight “so compelling that if they watch [casual fans could] get hooked on the sport for life.”

For his part, Oscar Valdez (28-0) wasn’t so sure, saying “I’m not going to go out and try and give a Fight of The Year or KO of the year, or do something crazy like that,” touting his preparation of “a Plan A and a Plan B.” After suffering a broken jaw in one such fight of the year contender vs Scott Quigg in 2018, Valdez had undergone a makeover, signing on with Eddy Reynoso, trainer of Canelo Alvarez. Reynoso has taken Valdez, a devotee of the “take a punch to land a punch” school of boxing, and tuned up his defense, seeking to make a boxer-puncher out of the slugger. And I suppose having your jaw wired shut for two months might make you receptive to reconsidering that whole hitting-without-getting-hit idea.

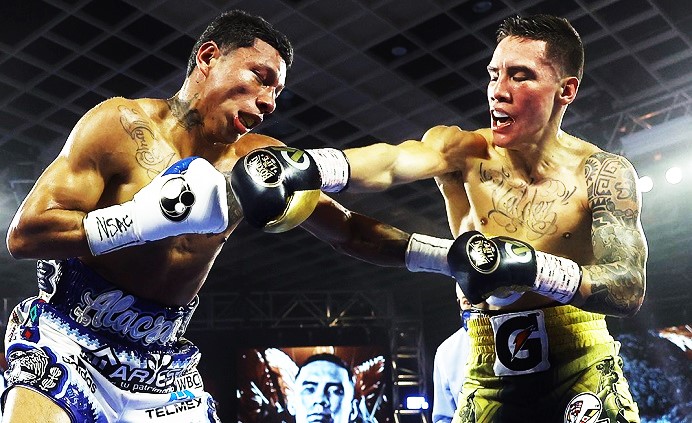

Valdez, the two-time Olympian, went on to notch four wins under his new trainer, three by KO or stoppage, suggesting Reynoso’s goal of making a complete fighter out of him was sapping none of his power or willingness to engage. Still, some of the performances were less-than-impressive, including a controversial seventh round stoppage of Adam Lopez after Valdez was knocked down and behind on the cards. These uneven performances, along with Berchelt’s five-inch reach advantage, 33 knockouts, and natural size, made “El Alacrán” the favorite. Come fight night, this translated to a six pound advantage on the scales, and a -300 nod on the sportsbooks. Berchelt (37-1) was making his sixth defense of the WBC belt, and looking to send a 34th fighter to the canvas.

Unlike Valdez, Berchelt has gone through no identity crisis or made any efforts to bolster his defense. Instead, in the words of Andre Ward, his offense, a prodigious 81 punch-per-round average in his previous six title defenses, “allows him to not get hit… when maybe he should.” So, all agreed, we had the makings of a classic, a clash between two offensively-minded fighters, one who could fall back into old habits and look for a brawl, and another with a desire to stand toe-to-toe from post to post.

The Result

As both men circled to their left in the opening rounds, Valdez looked like a last-minute invite to an intimate party: by turns stiff, jumpy, and nervous. Meanwhile, Berchelt, the vaunted offensive machine, restrained himself to pawing with his left lead. So far it was hard to see any war brewing, despite some blood coming from Berchelt’s nose, courtesy of Valdez’s sharp jab.

By the third, Valdez was settling in, boxing well, and forcing a run-and-gun affair. This neutralized much of “The Scorpion’s” power and limited his punch output. Valdez deployed a few maneuvers to avoid being trapped and pummeled. First, he would sling his fearsome left hook as he slid or rolled out of danger. Second, he started flirting with the southpaw stance to give him another route to sneak out of corners. Third, he tied Berchelt up in the clinch, forcing a reset in the center of the ring. These tactics limited Berchelt to only a few landed punches, such as the overhand right that connected squarely on Valdez’s chin before his escape from the ropes.

As we passed the halfway point in the fourth, everything changed. Berchelt continued to back Valdez up, and it looked like he might be able to induce the smaller man to stand and trade, when a left hook caromed off Berchelt’s unprotected temple, stealing his equilibrium away and wobbling his legs. With about a minute left in the round, Valdez ratcheted up the pressure, only to have Berchelt battle back, throwing looping shots from stiff legs. Valdez’s left hook continued to find a home on the right side of Berchelt’s head, and referee Russell Mora called a technical knockdown when Miguel stumbled against the ropes, the result of a push, not a punch, to this writer’s eye.

After what Berchelt and his corner must have thought was an altogether too short minute, the fifth began with the champion on his bicycle, trying to regain his legs, and perhaps his wits. “Show me something,” exhorted Mora, while a patient Valdez stalked the shaky Berchelt. Valdez seemed to know that the left hook would be the punch to close the show sooner or later, looking to set it up off the straight right to the body, but also timing a lunging Berchelt with the right hand for good measure. But as the smoke cleared from each of these punishing attacks, “The Scorpion” still came forward like the stuff of nightmares.

In rounds six and seven, Miguel seemed to have miraculously recovered, winning at least one of the two rounds. He walked Valdez down across both frames, and Oscar indulged him briefly in the pocket, even as he went back to his toolkit to escape any protracted battles. But Berchelt’s successes proved a short-lived interlude separating his disastrous fourth and fifth rounds from what would turn out to be the battle’s dramatic conclusion.

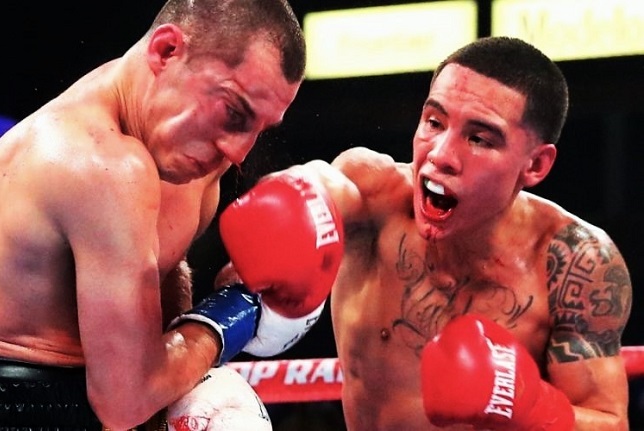

The tenor and pacing of the duel returned to the tactical boxing match that Valdez had so effectively imposed on El Alacrán in the early going. Valdez, caught between styles no longer, fought smoothly off of his back foot for the remainder of the match, beating a fighting retreat before pirouetting out of danger or tying up to get off the ropes. He dabbled more readily in the southpaw stance as well, switch-hitting to stay mobile. In the ninth a southpaw right uppercut touched off a combination that knocked the champion down. Worried about Berchelt’s safety, and with the scores slipping away, both Mora and the champion’s corner talked of stopping the fight before round ten got underway.

Maybe thinking he had no other option, a desperate Berchelt chased Valdez wildly in the final seconds of that round. Valdez backpedaled, slipped, and rolled, before planting his feet and uncorking a monstrous left hook that landed flush, ending the fight one second before the bell could end the round. Berchelt crashed to the canvas unconscious, Russell Mora waved the fight off, and doctors rushed in to care for Berchelt, who eventually regained consciousness and was responsive as he was taken to an area hospital. As of this writing he has been released from hospital after being held for observation and a battery of tests found no reason for concern.

What’s Next?

Valdez, doubted by many, including his idol, Julio Cesar Chavez, said post-fight “there’s nothing better in life than proving people wrong.” And prove so many wrong he did, as he put on a boxing master class last night, keeping the dangerous Berchelt at bay with a crisp jab, control of the ring, and, when he needed it, fight-stopping power of his own. In his own way, he even proved himself wrong, offering up not a war, but certainly a career-best performance and contender for knockout of the year.

Next, Valdez will most likely defend his new title belt against some of his fellow Top Rank fighters in Shakur Stevenson, or the winner of Frampton vs Herring. And when he does, he’s unlikely to re-enter the squared circle as the underdog. For now though, Valdez can return to his family and his farm of exotic reptiles as, once again, a reigning champion. As for Berchelt, a long rest and a careful look at his options are in order. He has nothing to be ashamed of, but maybe, as his rival did, it’s time to retool. And revisit that whole hitting-without-getting-hit idea. — Harry Meyerson