Can The Great American Novel Be A Boxing Novel?

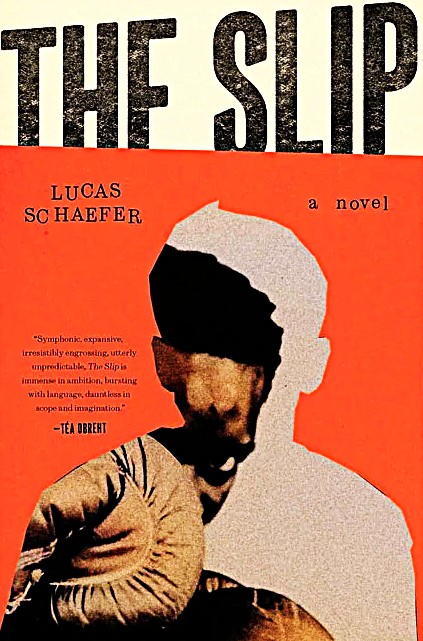

While reading Lucas Schaefer’s debut novel The Slip, I wondered: Could it be possible that at this late date we find ourselves in the midst of a Golden Age for boxing literature?

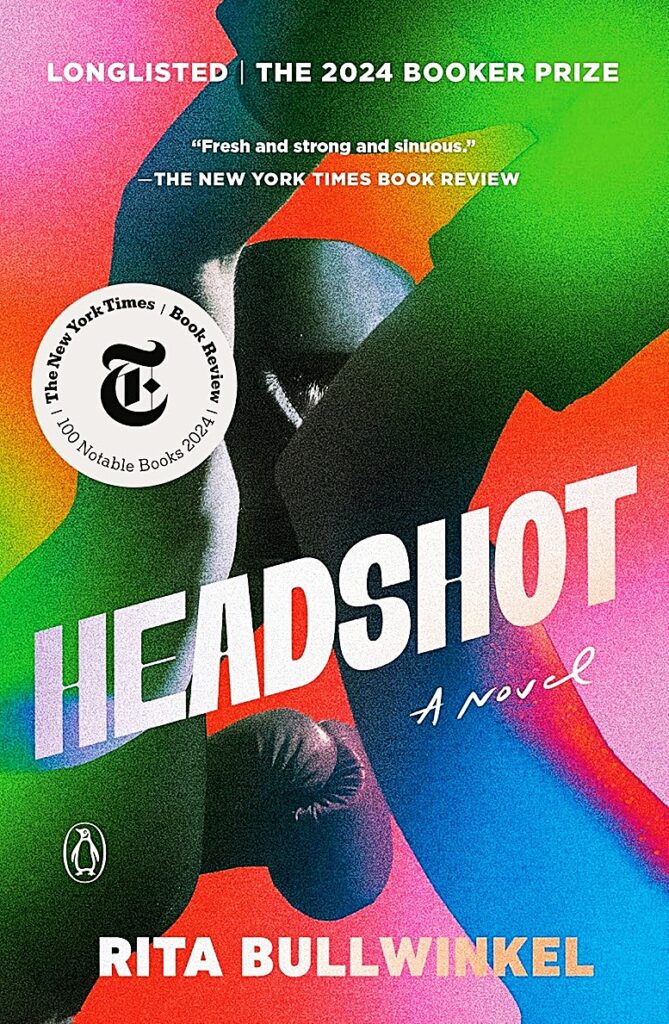

Before you get too skeptical, consider that The Slip just won The Kirkus Prize in fiction, and I expect more literary plaudits are on their way. And just last year, Rita Bullwinkel’s slim novel Headshot, set entirely within a girl’s amateur boxing tournament, was longlisted for the Booker Prize and was a finalist for the Pulitzer.

Great boxing literature isn’t relegated to fiction and every year there are numerous nonfiction titles — histories, biographies, memoirs – that merit attention and this year is no different. Donald McRae’s The Last Bell and Anna Whitman’s Soft Tissue Damage spring to mind. Then there are the confessional poems of Raisa Tolchinsky’s Glass Jaw, and the exuberant poetic experimentation of Eloisa Amezcua’s Fighting Is Like a Wife. And there’s Michael Winkler’s genre-exploding novel Grimmish, which has to be read to be believed.

Boxing as a publicly accessible and culturally relevant sport might be in a precarious place at the moment, but boxing as a subject for literature is thriving. And in Lucas Schaefer’s The Slip, boxing is the social glue that binds its disparate characters together.

More specifically, it’s the boxing gym that connects those characters. The novel begins with Bob Alexander, a 68-year-old “semi-affable curmudgeon” and member of the gym’s “First Thingers,” an informal group that regularly attends the gym’s first class of the day and includes money managers, realtors, and a district court judge. The cast spirals out from the boxing gym to include a young female cop, a phone sex operator, a former boxer turned Director of Hospitality at an eldercare center, and more than a dozen others.

The novel is expansive, “maximalist” in scope. In that regard, it has less in common with Headshot’s minimalist prose than say, Joyce Carol Oates’ undervalued A Book of American Martyrs, which concerns an abortion provider, the fundamentalist who murders him, and their respective daughters, one of which becomes a pro boxer.

Not only does Schaefer’s novel move in and out between dozens of characters, it weaves between decades, from 1998 to 2014. At the heart of the story is an unsolved mystery, described on the opening page by a newspaper clipping with the headline: “Ten Years Later, Still No Sign of Missing Teen.” The teen in question is Nathaniel Rothstein, nephew of First Thinger Bob Alexander, who had been staying with Bob at his home in Austin, Texas. Before he suddenly went missing, Nathaniel’s summer had been filled with volunteering at the eldercare center and taking his first lessons at the boxing gym.

Although the disappearance accounts for the heart of the plot, it is the boxing gym – Terry Tucker’s Boxing Gym – that is the heart of the novel. Some of Schaefer’s most eloquent, textured prose can be found in his descriptions of the gym and the everyday transcendence happening there.

People came and went, the gym remained. It didn’t stay the same, exactly. Year after year it became ever more itself. Inside, the walls were covered in tattered fight posters over which Terry was forever stapling fresh ones, fights at the Alamodome, fights at Austin Coliseum, so many fights it seemed one could drain the walls of cement and insulation and the building would stand on the strength of those posters alone … In the gravel lot, patrons pulled workout bags from trunks or backseats, then started toward the garage doors.

In interviews, Schaefer has explained the inspiration behind Terry Tucker’s Boxing Gym. Newly-arrived in Austin some twenty years back, Schaefer began attending evening classes at Lord’s Gym and the place clearly left quite an impression. Operated by Richard Lord, Austin’s temple of fistiana has produced champions like Jesus “El Matador” Chavez and Anissa “The Assassin” Zamarron. Lord’s Gym was also the subject of Frederick Wiseman’s 2010 documentary “Boxing Gym,” a fascinating companion piece now to The Slip.

Like so many gyms, duct tape is ubiquitous in Terry Tucker’s Boxing Gym, and we encounter David’s favorite heavy bag “mummified from head to toe” with the stuff. “Alone in the thicket of heavy bags, David swung his arms in a half-hearted shoulder stretch, regarded his world-weary competitor.” It is interesting that Schaefer uses the term “world-weary” to describe the heavy bag. There is a German term, Weltschmerz, which is often translated as “world-weariness.” It is used to express the melancholy that arises from one’s sense that the world just isn’t quite how we imagined it would be.

Taking another step, I think Weltzschmerz prods us to consider that when we say “the world,” we often simply mean ourselves. Because what is the world except what we see of it, and how we see it? Our weariness stems from our sense that we are not how we imagined we would be, that our lives are not as exciting or adventurous or fulfilling as we’d daydreamed all those past-lives ago, as bright-eyed children not yet benumbed by the endless errands of adulthood.

In the gym, Schaefer’s characters fire punches in the ring or at the heavy bag and physical exertion mixes with, even enables, daydreaming. In one scene, David, the Director of Hospitality, remembers back to his younger days of potential in the gym as he and his cohort

turned their fists sideways and found rhythm with the speed bags, as they learned to make the heavy bags swing, they felt inside themselves, despite themselves, the tug of possibility, and every smack of glove to bag, or fist to face, began to sound a little like What if?

Schaefer puts us next to David, decades later, still at the now-mummified heavy bag.

On rare days like today, when he stuffed his resentments and his jealousies and his regrets into his gloves and raised his fists to his face, he forgot his iffy knees and added girth. He forgot his forty-seven-year-old self altogether … In this moment, David is no longer the Director of Hospitality at Shoal Creek Rehabilitation. He is David the future lawyer, the one-day businessman, the someday therapist. David the maybe-not-a-tomato-can, who takes it nine rounds in Alvarado and wakes the next morning bruised but ready for more.

The central storyline of The Slip is a mystery plot, a disappearance. That plotline delivers, and I’m not looking to spoil it’s conclusion for you. What The Slip does, even more effectively than revealing its clues and twists regarding the missing teen, is remind us that although we like to assume such mysteries are located within other people, we are often more of a mystery to ourselves.

Characters change and transform all throughout the novel. Some are looking to become something new. Some are simply looking to escape what they’ve been. Terry Tucker’s Boxing Gym is the space where those people are looking to change. Maybe it’s an amateur looking to turn pro. Maybe it’s a woman looking to gain confidence and assertiveness. Maybe it’s a middle-aged office worker looking to lose fifteen pounds. In one of my favorite lines from the novel, Schaefer writes “They release themselves from themselves.”

Putting the book down, one mystery revealed and tallying my own ‘What ifs,’ I’m left wondering: Can the Great American novel be a boxing novel? Does The Slip belong alongside Huck Finn, Moby Dick, and The Grapes of Wrath? That’s not for me to decide, certainly not today. What has posterity ever done for me, as one of my college professors liked to say. But heck, why not? Is there a better metaphor for the United States in the 21st century than a sport in which two people beat the crap out of one another for diminishing returns, while most likely being swindled by somebody on the business end of the deal?

What’s important today is that with The Slip, Lucas Schaefer swings big and his aim is true. Let the future decide where he ranks. Right now, just enjoy a damn fine book. –Andrew Rihn