The Rumble In The Jungle

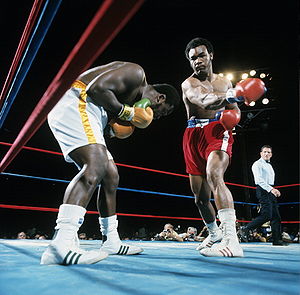

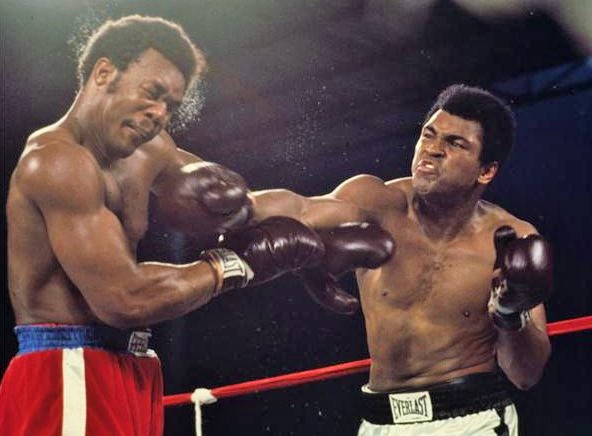

There have been bigger, more lucrative boxing matches, but few more momentous or memorable. When heavyweights George Foreman and Muhammad Ali clashed in a country then called Zaire in the heart of Africa 40 years ago this week, the world witnessed one of the most fascinating sporting events ever staged. It remains a singular contest in boxing history: not only the first heavyweight championship bout ever held on the African continent, but the battle which redeemed the career and the political stand of arguably the most famous and extraordinary fighter in all of boxing history: Muhammad Ali.

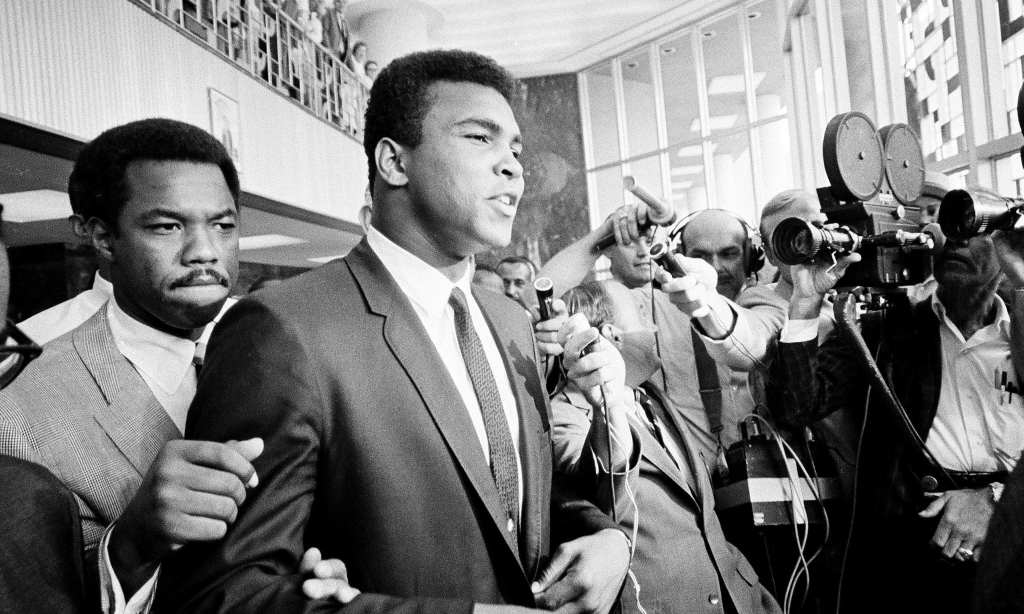

Before this fight Ali was regarded as an exceptional heavyweight champion, without question in the top ten of all-time. And his conversion to Islam, his joining the Black Muslims, and his refusal to be drafted into the army during the Vietnam War had all combined to transform him into a divisive political figure and one of the most famous people on the planet. But his astonishing victory over George Foreman on October 30, 1974, took all of this to another level entirely.

Thus Ali vs Foreman will forever be more than a boxing match. If any sporting events can be regarded as genuinely significant milestones in those turbulent times in American history — during the years of bitter division, assassinations, race riots, war and the civil rights movement — two boxing matches are near the top of the list. One is the first Ali-Frazier fight in 1971. And the other is “The Rumble in the Jungle.”

The story is well known. Shortly after Cassius Clay “shook up the world” and won the heavyweight crown from Sonny Liston in 1964, he announced his conversion to Islam and his membership in the Black Muslims led by Elijah Muhammad. He changed his name to Muhammad Ali and spoke candidly of his political convictions, ones which viewed the racial divide in America as insoluble. A few years later the Vietnam War raged on and Ali was called to the draft, but the heavyweight champion of the world refused to step over that symbolic line and serve his country. He was promptly arrested, stripped of both his championship and his license to box, and regarded by most of America as, at best, an ungrateful citizen, and at worst, a traitor.

But Ali stuck to his convictions, the central one being that, as he put it: “I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be what I want.”

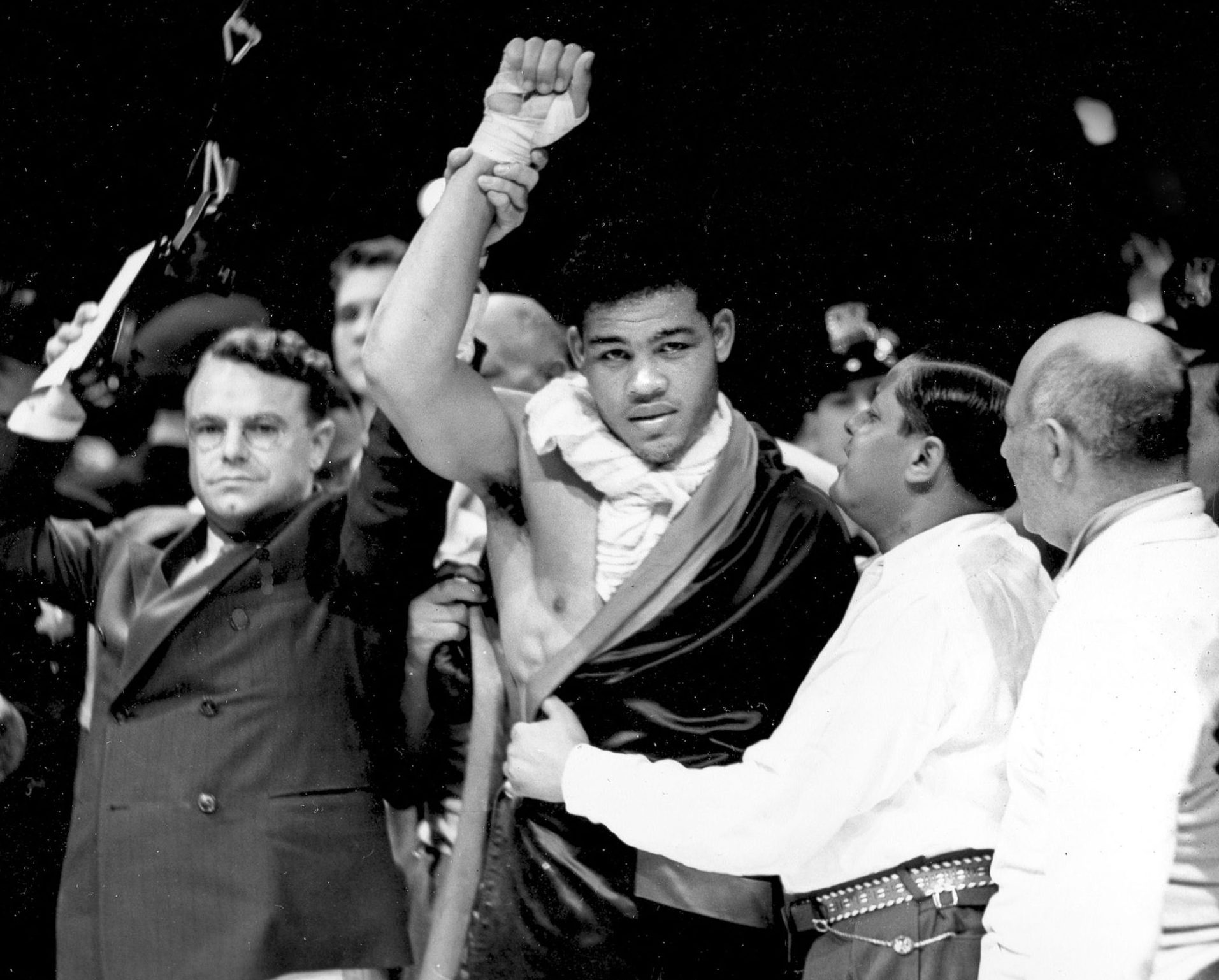

For a prominent black man, let alone the heavyweight champion of the world, to utter such words in a brash voice was something of a cultural thunderclap in 1964. Bear in mind, when Ali was making this proclamation and others like it, we were less than two decades removed from the reign of Joe Louis, only the the second black heavyweight champion in history. Louis knew the score and had conformed to expectations in an America still traumatized by Jack Johnson and where in many states people wouldn’t dream of welcoming “Joltin’ Joe” to their country club or show him to a preferred table in an upscale restaurant. Louis accepted the situation, knew his place, and when America entered World War II, he enlisted in the war effort and did all that was asked of him. In return, the Internal Revenue Service took all his money and hounded him until the day he died.

So it was Ali who let white America know that the rules had changed and that this black heavyweight champion was to be not so agreeable. He had a mind of his own, a vision that transcended America, and a courageous desire to assert his individuality. He rejected Christianity, took on a new name, and in the process, perhaps unwittingly, became part of a cultural and political struggle for emancipation and equal rights which, in some ways, has never ended. (And if you doubt that, I have two words for you: Ferguson, Missouri.)

Indeed, the seeds, as it were, of Ali’s great comeback, or at least its symbolic and political significance, were sown almost a decade before, after Ali had announced his conversion to Islam. In 1965, now a world figure, Ali journeyed to Africa, visiting heads of state in Ghana and Egypt and watching throngs of people crowd the roadways, the mobs chanting Ali, Ali, Ali. As it has been said of that trip, this was when Cassius Clay truly became Muhammad Ali.

Thus the symbolism of Ali regaining the heavyweight title in the land of his ancestors, the continent which represented to America the horror of slavery, cannot be overstated. Here was the only black champion since Jack Johnson who openly refused to play by white America’s rules, who had rejected the name of his ancestors’ American slave master, had dared to defy the might of the U.S. government and been condemned, humbled and unjustly stripped of his championship, and he was coming to Africa of all places to reclaim his crown. And none of this was lost on the people of Zaire, a nation free now of their Western colonial masters. From the moment his plane touched down, there was no doubt as to which man they wanted to win. Ali was their champion, the one they identified with, the one they loved.

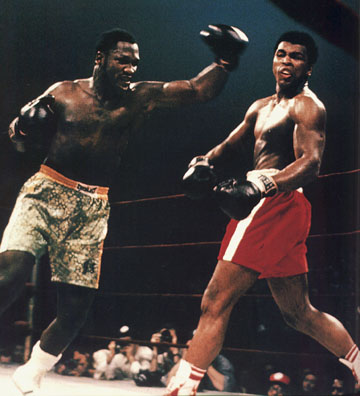

But despite the incredible theater, despite the politics and the symbolism, there was in the end a literal fight to be fought. And most thought Ali could not win it. His long banishment from boxing finally ended, Ali returned in 1970 to defeat top contenders Jerry Quarry and Oscar Bonavena, before losing by decision to champion Joe Frazier, and even his most devoted followers had to concede, the new Ali lacked much of the quickness and mobility of the pre-exile version.

Over the next two years, Ali stayed active and won a long series of bouts, before losing to little known contender Ken Norton. But during this same period, a new heavyweight had emerged — younger, bigger, stronger — and the boxing world was still coming to terms with George Foreman’s astonishingly violent two round demolition of Joe Frazier while Muhammad nursed the broken jaw Norton had bestowed him.

Ali barely outpointed Norton in a rematch and then won a decision over Frazier. But between those two matches, Foreman, like some modern day Goliath, impassively strode out of his lair and annihilated Norton, the fighter who had given Ali two of his toughest battles, in five brutally one-sided minutes. People considered how the younger, bigger Foreman had, with seeming ease, decimated the two men who had defeated Ali and their imaginations simply could not contemplate an Ali victory. As Howard Cosell put it: “Against George Foreman? So young? So strong? So fearless? Against George Foreman? Who does away with his opponents, one after another, in less than three rounds? It is hard for me to conjure with that.”

So, as Ali himself liked to say, the stage was set. Set for a most extraordinary exhibition of boxing skill. Set for a dramatic upset. Set for history. And set for the full flowering of the legend of Muhammad Ali, a charismatic and controversial figure, now larger than life, and a heavyweight boxer as good or better than any we have seen, before or since.

40 years. Hard to believe. And so for that reason, and many others, we choose to mark this historic contest the best way we can. With seven days of articles and remembrances, videos and reviews. We figure it’s the least we can do.

I look forward to Rumble Week.

Pingback: Dan Milaggi