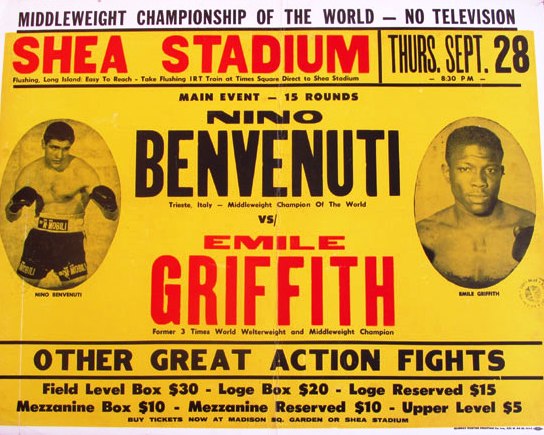

Sept. 29, 1967: Griffith vs Benvenuti II

“I would have quit, but I didn’t know how to do anything else but fight.”

Beyond the mythologies and whimsical fairy tales full of heroes who sneered at adversity are those who reach their pedestal because they had no other choice. Does that make them more heroic, or less? Emile Griffith ended a man’s life in a 1962 welterweight title fight, albeit aided by a horrific refereeing decision, and considered never fighting again. Maybe in quitting Griffith would have avoided the grief that weighed on him for decades, but he would have been one of many champions to lose and regain their title. In return for staying the course he etched his greatness in stone by again losing the welterweight title and regaining it, and then moving up to tackle middleweights.

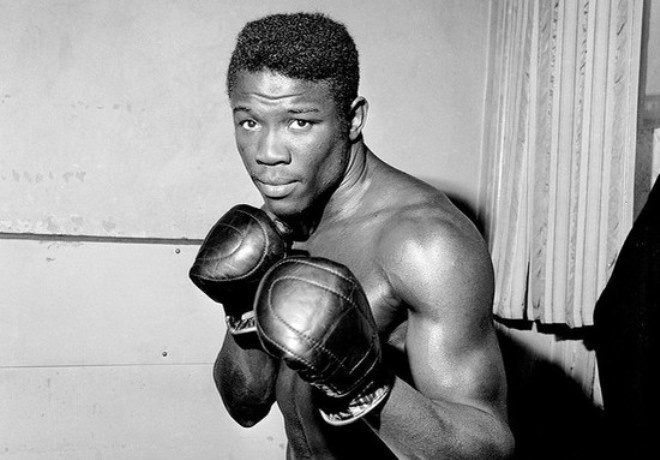

Though boxing didn’t find Emile Griffith until he was in his late teens, the St. Thomas native took to the sport quickly, and likely because he was introduced very early to high level pugilism through Gil Clancy, one of the best trainers in the game. Griffith never even imagined becoming a boxer, but at the age of 20 he won the New York Golden Gloves as a welterweight and turned professional shortly thereafter. The 1960s fight scene in New York City might have been a rough one, but with Clancy as trainer and co-manager, Griffith was better-equipped than most of the more experienced fighters he stared down. Before long Emile could no longer call himself inexperienced, winning the welterweight title from Paret with fewer than four years in boxing.

Griffith wasn’t even a big welterweight, frequently weighing in under the limit, but that didn’t stop him from from moving to middleweight, having already owned wins over most of the top 10 in his division anyway. Past that, the time was right; middleweight champion Dick Tiger could be defeated, and Griffith overcame 2-to-1 odds to hand Tiger his 17th loss and take the title. In less than a decade, Griffith had gone from working for a hat maker to being a two-division world champion.

Giovanni “Nino” Benvenuti was familiar with the concept of heroism, as he had become one to Italy by seizing Griffith’s middleweight crown in April of 1967. Upon arriving in Milan afterward, Benvenuti was swarmed by fans greeting their newest champion. Sandro Lopopolo won the super lightweight title one year earlier, but the middleweight title was far more prestigious. And Benvenuti had movie star looks. “People come up to me and just look,” Benvenuti said after becoming champion. “They don’t say anything, they just look or hand me a paper to sign an autograph. I like that part, but sometimes my hand gets tired from so many autographs.”

The first fight at Madison Square Garden carried no rematch clause as such maneuvers weren’t allowed by the state commission at the time, so Griffith and Benvenuti’s teams shook hands, informally agreeing to the rematch. Overeager for a return, Griffith was in such a hurry to provide his own autograph on a contract that Clancy yanked the papers away to double check the numbers. A nasal cut suffered by Benvenuti in the first fight delayed the rematch though, but after surgery all was well and the bout was rescheduled from July to September.

Benvenuti departed for New York on the ocean liner Raffaello, and press photos were sent out of him skipping rope on the ship’s deck. He was received in New York City by swaths of people and a plane towing a sign that read “Benvenuto Benvenuti.” The champion set up camp in Haines Falls, a hamlet far north of New York City, and employed Holly Mims and Bennie Briscoe for sparring. Often Benvenuti trained to classical music from Beethoven, Bach and Wagner, and in the evening he drank wine and ate spaghetti. He was an Italian stereotype, but with the contemporary edge of a Beatles haircut.

Reporters were constantly giving Griffith an out, suggesting he hadn’t trained well for the first Benvenuti fight or took him lightly. The former champion scoffed rudely at their suggestions, telling press when official contracts were signed just ten days before the bout, “I’m going to be much better. I was bad last time. I was right hand crazy. I didn’t jab and I didn’t go to the body enough. This time I am going to get the title back.”

Nearly five thousand Italians flew from Rome and Bologna for the fight. According to Griffith’s other manager, Howie Albert, Griffith had been upset about Benvenuti’s Italian supporters waving their flags during the first bout and had Albert order five thousand American flags to distribute among the fans. “Now maybe with the American flags there will be plenty of noise for Emile. That should help counteract the Italians’ yelling.”

Odds were close before the weigh-in, hovering about 6-to-5 in favor of Benvenuti, and they held fast when he scaled in one pound under the limit but a full five pounds heavier than the challenger. Clancy was confident that Griffith would regain the title, praising his work ethic and training habits. “But if [Griffith] doesn’t give me what I want this time, I’ll slap him,” Clancy warned one reporter for The New York Times. “He hates it but it wakes him up. I did it to him in the amateurs and he knocked out a guy in the next round. I did it to him in the first fight with the late Benny Paret and he knocked him out in the next round.”

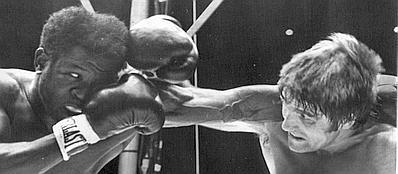

Any talk of a knockout was hyperbole, but Griffith attacked in the first round as if he meant to score one. It never came, but Griffith’s rougher tactics made a dent as he rocked the champion and bloodied his nose. The Italian stole the momentum back for a few rounds, sidestepping Griffith’s rushes and rocking him in round two, but before long the fight went back to the trenches, and that wasn’t Nino’s game, whether he had a weight advantage or not. A shoulder to the ribs and distracting headbutts from Griffith were repaid with rabbit punches in the clinch and both fighters were warned repeatedly in round four.

Through all the heeling and pushing off with elbows, Benvenuti’s ability to hook off his jab created some separation in the middle rounds and Griffith was kept at bay for a short time. Griffith’s jab was a stunner of a shot from a distance, but it was a short hook in close that shook Benvenuti in the eighth, and in round nine he was sent down, though it was ruled a slip. After that Benvenuti faded badly, flurrying in round thirteen as a sort of last hurrah. He went down officially off a counter right hand in the next round and took a mandatory eight count despite his protests, and that was it. Referee Walsh inexplicably scored the bout even, but he was overruled by two judges and Griffith became only the third fighter in history to regain the middleweight title.

Milan’s Corriere Della Sera said after the fight, “Benvenuti found himself in front of a new and largely unpredictable Griffith, very different from the Griffith of last April, a bold Griffith who swung his deadly right and then struck with his precise left.” However Muhammad Ali, deposed heavyweight champion, consoled Benvenuti by insisting the fight should have been a draw before telling him, “Don’t worry, you’re the best white fighter around.”

But Griffith had become a two-time middleweight champion, in addition to his three-time annexation of the welterweight title. Writer Murray Rose said the 29-year-old was closing in on Sugar Ray Robinson numbers. “Give the boy time,” Rose stated. Griffith’s deeds already made him immortal. That he achieved what he did after the horror of Benny Paret’s death makes him a hero. — Patrick Connor