On Quitting

There’s quitting. And then there’s quitting. After all, this is boxing, the most dangerous of sports. Only a moron would insist that a fighter should never, ever, under any circumstance, surrender. For example, we all wish Magomed Abdusalamov back in 2013 had told his corner he couldn’t go on, but he did not and ended up suffering irreparable brain damage. Those of us outside the ring need to think carefully before judging the brave people who risk their lives when they step through the ropes and who may, after taking some serious punishment or suffering an injury, decide to wave a white flag and live to fight another day.

But then there’s quitting. As in failing to fulfil the fundamental obligation of competing to the best of one’s abilities. Of failing to have the courage to pursue victory even when it appears to be a lost cause. There’s a reason fans fervently applaud athletes, in any sport, who keep trying, keep working, even when defeat seems certain. There’s a reason why they revere the fighters who overcome injury or adversity to win. And there’s a reason why fans boo quitters.

The pact between boxers and fans needs to be considered here. No one buys a ticket to a fight card without a certain expectation, that being that the boxers are going to give everything they have to compete and pursue victory. This is a tacit understanding between fight fan and prizefighter. People watch boxing, or competitive sports in general, because it’s exciting. And the reason it’s exciting is because the competitors give all they have to the struggle for victory. Or so one hopes.

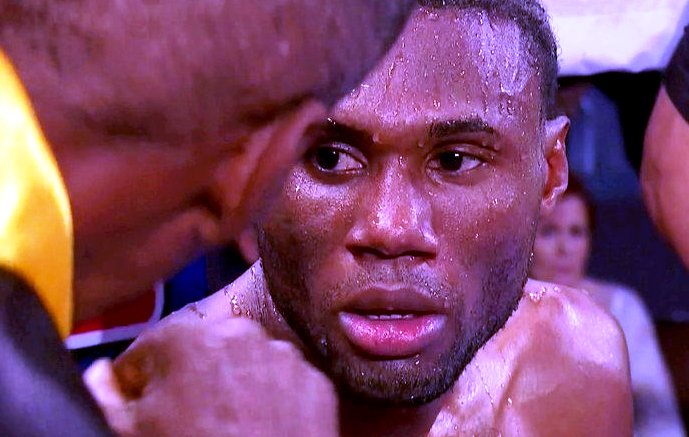

On Saturday night, Nicholas Walters quit after seven one-sided rounds against Vasyl Lomachenko. While not a major fight in the sense that it attracted mainstream attention or was a pay-per-view event, this was still one of the bigger, more anticipated match-ups of the year. Walters was undefeated and a former champion; Lomachenko is regarded as a spectacularly gifted talent. No one questioned that this qualified as one of the most attractive match-ups that could be made in the sport today.

But great matches don’t always mean great action and drama, and for seven rounds Lomachenko was in almost complete control. This should not have come as a great surprise. We all knew that in terms of speed, footwork, versatility and talent, the man they call “Hi-Tech” had clear advantages. However, the reason this was viewed as an attractive match was because Walters had in his fists the potential to erase Lomachenko’s advantages with a single well-timed blow. He was, ostensibly at least, the more powerful fighter, and those who viewed him as a major challenge for Lomachenko anticipated him giving up rounds to his busier opponent while he looked to land the one or two hurtful shots that could reverse the momentum or even end the fight.

Walters was never floored, never cut, never seriously hurt. But when the bell rang for round eight he informed the referee he did not wish to continue. The match was awarded to champion Lomachenko as the crowd booed the Jamaican challenger. Did he deserve the boos? Should we view the fighter they call “Axe Man” with contempt? Or should we simply applaud Lomachenko for his victory and move on?

Either way, it would seem that quitting in boxing, something formerly viewed as a mortal sin, is more common and accepted than in the past. Once regarded as a shameful act, we see more often boxers do as Walters did on Saturday: concede defeat and simply refuse to keep fighting. Relatively recent examples which come to mind include: Victor Ortiz vs Marcos Maidana and Andre Berto; Julio Cesar Chaves Jr. vs Andrzej Fonfara; Oscar De La Hoya vs Manny Pacquiao; Mike Alvarado vs Brandon Rios III.

In all of these cases the loser of the match was lucid and seemingly capable of continuing, but they chose to quit. No one gets too exercised when this happens after several rounds of one-sided punishment, as in the case of Oscar when he was upset by “The Pacman.” But even in the other examples cited here, it seems the act of quitting did no more damage to the fighter’s reputation than the fact of losing. More and more, quitting appears to be just another way to lose a fight, but if that’s the case, it says something less than inspiring about the current state of the sport.

As noted, it’s difficult to criticize too harshly given the risks involved, and yet, in the not too distant past, quitting was regarded as just about the worst thing a boxer could ever do in the ring. There was a harsh code which all fighters understood: the referee could stop it, the boxer’s own corner might throw in the towel, but any pugilist worth his salt could never, ever quit. It would besmirch his honour, his integrity, his reputation, not to mention violate the aforementioned contract between prizefighter and the people in the stands putting up the cash for said prize: the boxer must fight with everything he’s got until he’s rendered incapable or the final bell tolls. Nothing less was acceptable.

When an aging Barney Ross defended his welterweight title against a ferocious young champion named Henry Armstrong in 1938, he took a terrible pounding for 15 rounds. In the late going, ringsiders called for the fight to be stopped. With no hope of winning, Ross’s own corner begged him to let them end it, but the proud champion wouldn’t even respond to their pleas. Ross was determined to finish on his feet and he did.

The year before, James Braddock had defended his heavyweight crown against one of the greatest boxers of all time, Joe Louis. Braddock had little answer for the Brown Bomber’s advantages in speed, strength and power. He took a savage beating for seven rounds before his manager, Joe Gould, told him he was going to ask the referee to stop the fight. From behind cut and swollen eyes Braddock glared at Gould, his closest friend and confidante. “You do,” he said, “and I’ll never talk to you again.” Louis stretched Braddock with a devastating right hand in the very next round.

Similarly, when the great Archie Moore challenged Rocky Marciano for the heavyweight crown in 1955, Moore started well, boxing smartly and even decking Marciano in the second round. But by the sixth, it was evident Moore could not win. Stronger, more powerful, Marciano’s relentless attack was simply too much. He floored Moore four times before referee Harry Kessler went to the challenger’s corner after the eighth round and asked about stopping it. “I would like to be counted out,” said Moore. And in round nine, he was. Such was the code.

In October of 1980, the late, great Muhammad Ali made the terrible mistake of coming back from retirement to face champion Larry Holmes. After the very first round Ali went to his corner knowing he couldn’t win; he also knew quitting was out of the question. He endured a terrible battering before the fight was finally stopped by his corner after ten completely one-sided rounds.

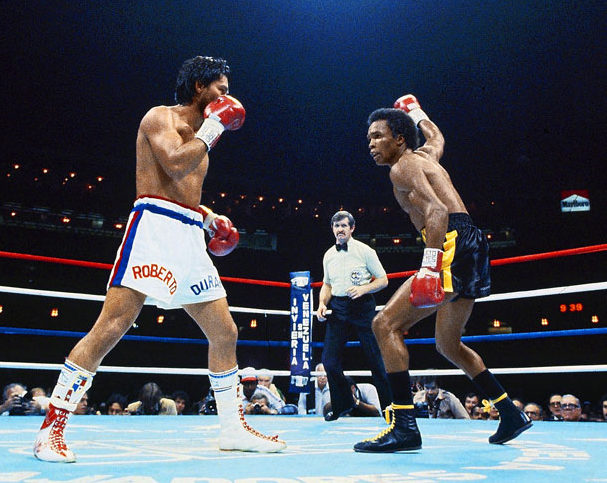

The uncompromising courage displayed by these fighters made what Roberto Duran did roughly six weeks after the Holmes-Ali fight all the more shocking. Facing Sugar Ray Leonard for the second time, Duran, the epitome of Latin machismo, abruptly threw up his arms and quit near the end of the eighth round of a competitive fight and the words “No mas” instantly entered the popular lexicon. The reaction at the time was swift and sure: Duran was condemned by all quarters. And yet in a few short years he regained his popularity, winning a third title from Davey Moore and going on to make millions in bouts with Marvin Hagler and Thomas Hearns. Who knows, maybe Duran’s enduring popularity in the years since made quitting seem not the disgraceful act it once was.

In 1994 Julio Cesar Chavez fought a rematch with Frankie “The Surgeon” Randall who had handed the three-division champion his first official defeat a few months previous. (I say “official” because the great Pernell Whitaker had totally outclassed Chavez the year before but the judges and their seeing-eye dogs scored it a draw.) Chavez and Randall engaged in another tough fight, both men giving and taking, with Randall once again appearing to have a decided edge. In the eighth round, a clash of heads produced a deep cut over Julio Cesar’s right eye and the referee asked ringside physician Flip Homansky to examine the injury. We’ll let Homansky finish the story: “It was a nasty gash and it was my impression Chavez didn’t want to continue. He shook his head twice to me. That was enough … If he had wanted to continue, I probably would have let him.”

Cuts happen; they’re part of the brutal game. But when the wound is bad enough to merit a visit with the doctor, a boxer knows the fight could be stopped at any moment, and the man with the cut usually loses. (Though not in this case; under WBC rules they went to the scorecards after Homansky and the ref stopped it and Chavez was declared the winner.) Fighters prone to cuts, such as Carmen Basilio, Bobby Chacon or Vito Antuofermo, would often plead with an examining doctor: “It’s okay, doc. I’m fine. Don’t stop it. I can go.” What did Chavez do? He shook his head, as if in distress, giving the doctor and referee little choice. There’s no way around it: Chavez quit. And then won.

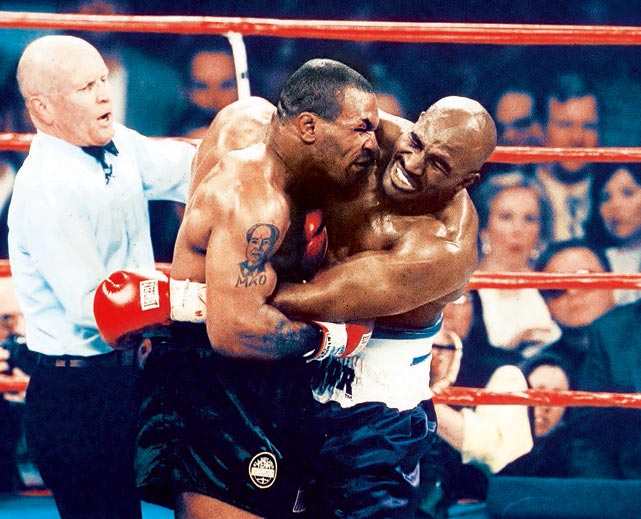

Boxers have found other creative ways to surrender. One of the more popular methods is to foul out. Doubtless, Mike Tyson displayed the best all-time example of this form of quitting in his rematch with Evander Holyfield. In the third round of what was shaping up to be another decisive win for The Real Deal, Tyson caved in to the pressure and applied his incisors to the tender flesh of Holyfield’s right auricle. The fact he had to bite Holyfield a second time to gain the desired result showed unequivocally that Tyson was no longer seeking to win, but instead choosing to lose on his own terms.

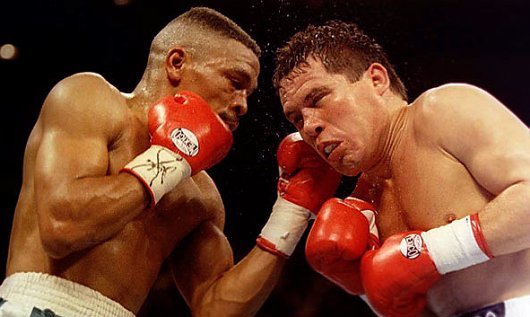

Another preferred method is that demonstrated by Sugar Shane Mosley in his 2011 fight with Manny Pacquiao. This quitting technique involves the boxer continuing to answer the bell, but making no effort to win the contest. Once Mosley felt the Pacman’s power and took a trip to the canvas in round three, he quit. Thereafter, round after boring, tedious round, Mosley retreated, held, and otherwise stalled the proceedings, never taking any chances to mix it up or risk his own safety.

Other examples of quitting come to mind: Alexis Arguello calmly remaining seated on the canvas to be counted out in his rematch with Aaron Pryor; Zab Judah taking a ten count against Amir Khan after absorbing a hard punch to the waistband of his trunks; a seemingly coherent Buster Douglas checking for blood while being counted out after a single right hand from Evander Holyfield; Kostya Tszyu surrendering in his corner to Ricky Hatton. What once was an unpardonable offense has become something almost accepted by fans and fighters alike.

Then again, the more judgemental among us need to think twice. After Andrew Golota quit against Mike Tyson in the second round of their fight in October of 2000, the Polish fighter was jeered and pelted with garbage, only for it to be later revealed that he had suffered a fractured cheekbone and a spine injury. How many of those throwing popcorn at Golota would have been willing to fight Mike Tyson with a broken face?

That said, no word has come down yet of serious injuries suffered by Nicholas Walters on Saturday night. And in the absence of such injuries, this boxing fan has no qualms about condemning the young man. Was he losing the fight? Was he being dominated? Absolutely. But in boxing, as in life, we don’t just throw in the towel when things don’t go according to plan. Walters owed it to himself to persevere, to keep throwing punches, to try and find a way to slow Lomachenko down and connect with some heavy shots. And he owed that effort to pugilism. In a time when so many elite-level boxers are, to put it bluntly, lousy competitors, this simple truth must not be overlooked.

— Michael Carbert

Golota is the master of getting out of there by fouling.