July 18, 1951: Walcott vs Charles III

If James Braddock is “The Cinderella Man,” then what do we call Arnold Cream, aka Jersey Joe Walcott? Braddock’s story of perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds eventually inspired Hollywood attention, but no movie has been made about Cream and his equally improbable triumph, perhaps because Walcott’s tale strains credulity to the breaking point. In truth, Jersey Joe’s story rates as even more exalting than Braddock’s when one factors in racial inequality in America before the Civil Rights movement, as well as the number of times Walcott had been written off by the pundits of the day. For years he couldn’t catch a break, in part because he was Black, but also because Jersey Joe was perceived as a no-hope journeyman, a perennial contender, who couldn’t, and wouldn’t, make the big time.

When he finally did get a shot for the title against “The Brown Bomber” in 1947, it was a double shock, first for his outclassing the great Louis, and then for not getting the decision he so obviously deserved, the verdict one of the worst in heavyweight history. But Louis knocked Walcott out in the rematch, and Jersey Joe went on to lose two more tries for the title against Ezzard Charles in ’49 and ’51, confirming the general feeling that there were some for whom fortune would never, ever smile. But while time and again the public thought they had seen the last of Walcott, Jersey Joe was nothing if not resilient. Heartbreaking setbacks were nothing new to him; he’d dealt with them his whole career.

Space does not allow for a detailing of all the misfortunes, crooked managers, and broken promises Walcott endured after he turned pro in 1930. It’s enough to say that by the time the winter of 1944 rolled around, Arnold Cream, living with his family in a dilapidated shack in Camden, New Jersey, had quit the fight game for good. He had already retired at least half a dozen times before that point to concentrate on steady work that didn’t threaten to drive him insane, such as hauling garbage or working in the shipyards, but this time it appeared it would stick. Joe had had only two fights in four years, now had six children to feed, and he lacked any kind of representation, no manager or promoter who believed in his talent.

Enter Vic Marsillo.

A New Jersey-based matchmaker hoping to develop a local heavyweight attraction in Camden, Marsillo approached the fighter and started talking up Joe’s talent, reminding him of his ability, his natural caginess, that slick move he had of walking away from an opponent before turning and ambushing him with a heavy right hand. But Walcott had heard it all before, had been sweet-talked many times by managers who eventually left him high and dry. Words alone weren’t going to get Walcott back in the ring.

So Marsillo hit upon what turned out to be the perfect gesture to give the crestfallen fighter the boost he needed. It was December, just before Christmas, and it was cold. Marsillo convinced his money man, promoter Felix Bocchicchio, to help him buy a ton of coal for Cream and his family. Marsillo delivered it personally, helped shovel it into the basement, and one Arnold Cream, family man and working stiff, was ecstatic. The security those black nuggets represented to him and his family could not be overstated. Buoyed by his new manager’s faith in him, Cream went back to being Jersey Joe Walcott and commenced training with renewed zeal.

From there, the old man’s career finally took off, a testament to what a little well-timed encouragement can do. He scored a series of big wins over Joe Baksi, Jimmy Bivins, Lee Oma and Joey Maxim, which in turn led, finally, to an overdue title shot. Robbed by the judges against Louis, knocked out in the rematch, still, Walcott simply refused to go away. After all, win or lose, he was finally making decent money.

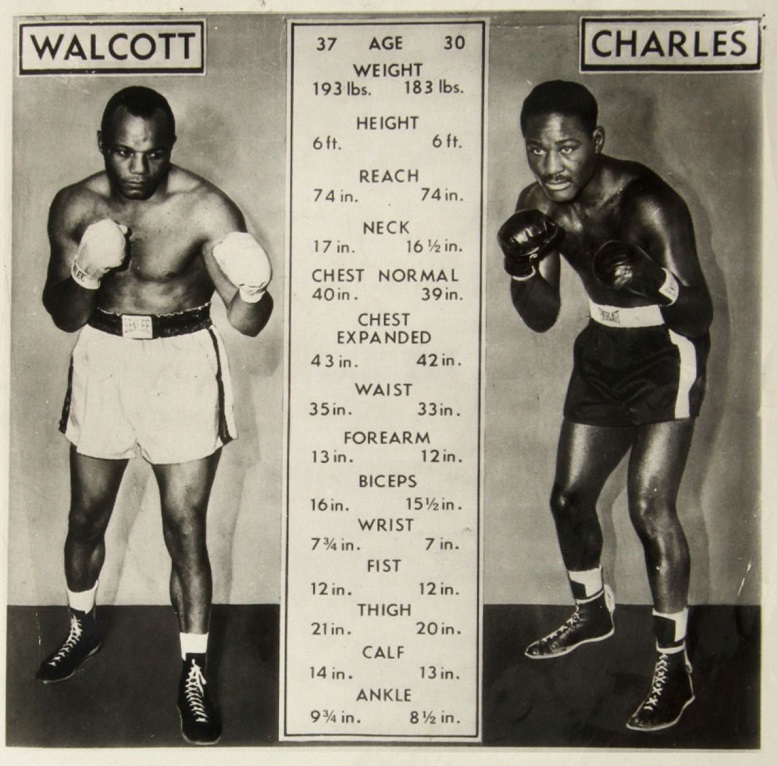

When Louis retired, Jersey Joe was matched with Ezzard Charles to decide the Brown Bomber’s successor, and he dropped a close decision to the former light-heavyweight and all-time great. But Walcott kept fighting, kept winning, got a rematch with Charles where he again dropped a fifteen round decision, but this time he gave Ezzard the toughest of struggles and many thought Jersey Joe had been robbed again. So, four months later, in Pittsburgh, the two rivals met for a third time, Walcott a nine-to-one underdog, because a victory in a record fifth attempt at the world championship was deemed just too improbable, the stuff of fairy tales, not real life.

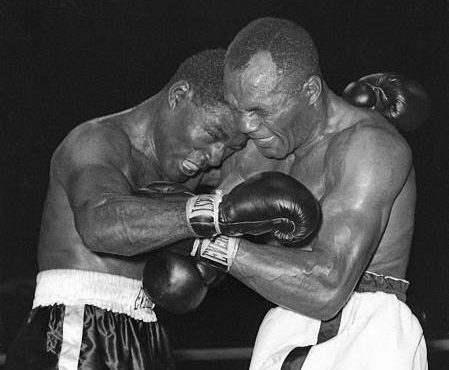

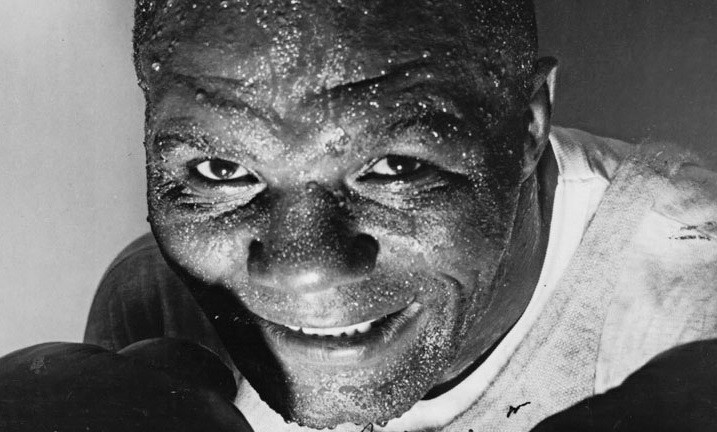

But there was Walcott, looking as good as ever, asserting himself in the third round with a hard right hand that stunned the champion and cut his cheek. In the fourth and fifth he had Charles covering up, and in the sixth Walcott started throwing heavy left hooks. Fighting with more fire than he ever did in their first two bouts, most ringsiders had him winning by a clear margin when the bell rang for round seven.

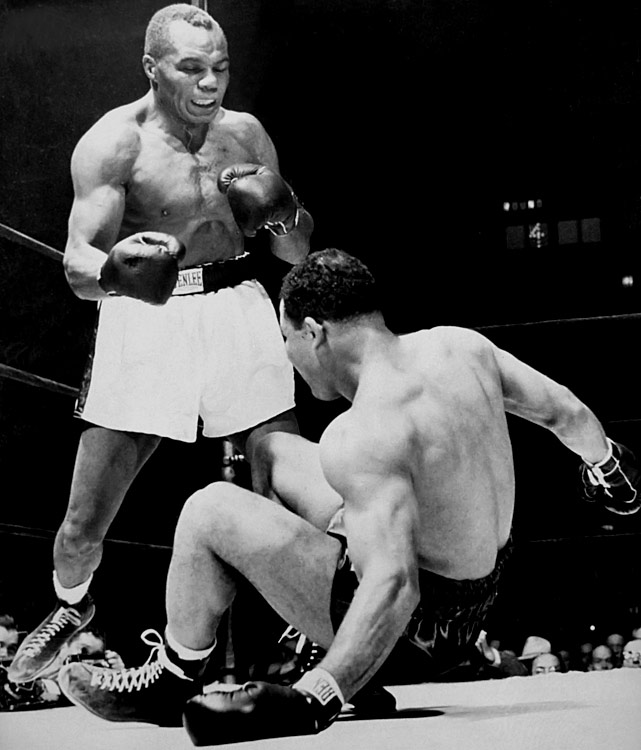

Charles came out aggressively, trying to reverse the tide, and he backed Jersey Joe into a corner where the fighters clinched. After the referee separated them, Walcott walked nonchalantly to ring center, as if he had nothing on his mind more menacing then taking an afternoon stroll to admire the summer flowers, and then, with perfect timing and rattlesnake quickness, he ripped a vicious counter left hook to Charles’ jaw.

The champion’s head recoiled as he sank to a crouch and then he toppled forward, landing flat on his face. Charles made a valiant effort to rise but collapsed again as the referee finished the count. The capacity crowd in Forbes Field looked on in stunned disbelief. Few had seen the punch, it was thrown with such sudden sharpness, and fewer still had expected such an outcome. Most had anticipated the younger, fresher Charles to win handily, further establishing himself as the man at the top of the heavyweight mountain; virtually no one foresaw the big underdog winning by knockout.

But, that’s what happened. Jersey Joe Walcott, after years of struggle, finally won the big one and, at 37 years of age, had become the oldest man to ever win the heavyweight title, a record that held until 1994 and George Foreman’s equally unlikely victory, also of the one punch variety, over Michael Moorer. Walcott would successfully defend against Charles before losing back-to-back bouts with Rocky Marciano, but those defeats, as memorable as they are, cannot erase the previous twenty-two years and all their twists and turns, nor Walcott’s Cinderella moment, his fairy tale victory, that huge left hook that finally brought not only the world title, but redemption. — Michael Carbert

Inspiring and beautiful.

I recognize that walking uppercut; it’s the same one used by George Foreman so casually in so many fights. Incredible!

Nice story. But where are the posts about the man who is the KO King to this day, who has been called the most ignored boxer in history, Archie Moore, the legendary “Old Mongoose”?

Here ya go: https://www.thefightcity.com/nov-30-1956-patterson-vs-moore-heavyweights-floyd-patterson-archie-moore-rocky-marciano-joe-louis-chicago/

https://www.thefightcity.com/archie-moore-vs-yvon-durelle-december-10-1958-moore-vs-durelle-montreal-forum-rocky-marciano-joey-maxim/

https://www.thefightcity.com/top-12-best-light-heavyweights-sam-langford-ezzard-charles-archie-moore-gene-tunney-boxing/

And stories on Moore’s fights with Joey Maxim and Rocky Marciano are in the works. Thanks for reading!

Jersey Joe put on the most fierce flurry I’ve seen for a heavyweight in fight #1 with Rocky. He lost, but Rocky said JJ hit him the hardest of all his opponents.

I read in a Joe Louis biography that some experts say that the Jersey knockdowns were the result of starvation rather than a lack of ability.