Hollow At Its Core

“Fighting Floyd Mayweather is a dose of cold reality.” — Jim Lampley

Despite his synonymy with boxing, Floyd Mayweather remains a superstar with whom fans have a tepid engagement. He is not beloved, nor does his career have many signature moments. If pressed to cite a instance representative of him, I suspect most people would invoke one in which he counts money on camera, or yells at his father, or screams in Larry Merchant’s face, rather than a dazzling instance of boxing skill. His career, in which he’s campaigned across divisions, surgically disassembling rivals from featherweight to middleweight, has been an exercise in managed risk, a one-sided drama in which he’s acted as the playwright, cast lead, theater owner, and lead actor. His May 2 fight with Manny Pacquiao will supposedly define his legacy, but that might be yet another misinterpretation of a career fashioned in a vacuum.

The single most important event in the creation of Floyd Mayweather, sports superstar, was his 2007 fight with Oscar De La Hoya. That contest, positioned by the media establishment as the last great prizefight, could trace its popularity as much to nostalgia for boxing pageantry as to the actual match. De La Hoya was fighting on old legs and his name was larger than his talent. He was, in other words, a mark: to be beaten and leveraged for his popularity by an ambitious young boxer who felt his skills had been overlooked. Sensing an opportunity to become a cultural star, Floyd enlivened HBO’s new 24/7 documentary series with his profane belligerence and audiences lapped it up.

Prior to this fight, few fans outside of boxing knew much about Floyd Mayweather. Despite his outstanding pedigree, his name hadn’t scaled the sport’s high walls. Floyd had won several amateur titles, a bronze medal at the Atlanta Olympics, the super featherweight title when he whipped Gennaro Hernandez, and at only 21 he was named The Ring’s Fighter of the Year. But despite his precocity, the widespread cultural fame Floyd coveted escaped him. It didn’t matter that he’d dissected the talented Diego Corrales or maliciously beaten Arturo Gatti, a popular fighter with a boisterous East Coast following. These men were famous only among boxing fans. Mayweather needed a foe whose fame could be wielded for his own purposes. Oscar De La Hoya was perfect.

Ask yourself, can you even remember Floyd’s fight with De La Hoya? Are any of its moments lodged in your memory, like other, indelible snapshots of recent boxing history? Did Floyd land any noteworthy combinations or stagger the Golden Boy even once? Oscar’s assault of Floyd’s midsection against the ropes, which may have been the fight’s most dynamic moment, hardly qualifies as a classic moment. It was the spectacle and anticipation of De La Hoya vs Mayweather, not its action, which made it memorable. What happened inside the ring was rote.

That fight is a representative sample of Floyd’s career versus the elite: sharp, pointed shots, little combination punching, and excellent defense. At the final bell, it was Oscar’s face, not Floyd’s, that was red and bruised, and Mayweather was rightfully deemed the winner. But for those who’d turned in to see boxing’s Michelangelo destructively mold the Golden Boy’s face, Floyd inflicted only modest damage. Casual watchers may have been perplexed by Mayweather’s supposed importance. If he was so good, why hadn’t he dominated?

Greatness, Obscured

More lasting than any individual sequences from Mayweather vs De La Hoya was the promulgation of “Money Mayweather,” a transparently materialistic, ceaselessly boring persona that may as well have been birthed by Vince McMahon. Its emphasis on wealth and fame resounded in a fragmented culture for which these are its last common referents. The most substantive thing about Floyd has always been his boxing skill, but it’s merely the foundation upon which his brand is built. In this sense, if his career can be likened to a Ferrari, his talent is the engine—intricate, sophisticated, and largely obscured—without which the gleaming apparatus cannot move.

Having established himself on a stage suited to his talent, Mayweather needed to continue picking suitably popular opponents to beat. Next was Ricky Hatton, an undefeated champion from Manchester whose fire would supposedly melt Floyd’s ice. Like every aggressive would-be conqueror, Hatton was easily beaten by someone with greater brains and ability. Mayweather out-boxed and out-guiled the “Hitman” on his way to a fantastic tenth round knockout, after which Floyd promptly retired. He cited his disenchantment with the sport as his reason for quitting, but few in boxing thought he’d be away for long. Floyd’s appetite for fame could not be satiated.

During Floyd’s two years away, Filipino sensation Manny Pacquiao bested Juan Manuel Marquez, David Diaz, Oscar De La Hoya, and Ricky Hatton, beating these last two fighters far more authoritatively than Floyd had. Meteorological metaphors (‘tornado’, ‘typhoon’, ‘tsunami’) have been exhausted when describing the stormy aggression of Pacquiao at his apex. His abandon was the opposite to Floyd’s caution, and for some, the antidote. Naturally, the sports world called for them to fight, but it never happened until this year.

After two years away it was not Pacquiao Floyd chose to return against but Marquez, a skilled combination puncher who fought two close matches with Manny. Floyd was criticized for deciding to return against a true lightweight, because Marquez, while a fabulous boxer, was moving up two weight divisions and would be fighting at a pronounced size handicap. It was rightfully seen as another opportunistic ploy by Mayweather, who was content accepting challenges solely if they unfolded on his terms.

In one of the most dominant performances of his career, Floyd won every minute of this bout, which serves as a fine microcosm of his success: a beautiful performance against a carefully chosen opponent who couldn’t threaten him and who Floyd operated on, as opposed to engaged with, as Manny Pacquiao might have. Mayweather was praised for his brilliance but the acclaim was tempered by the implicit belief he was supposed to win. Floyd had stacked the variables in his favour, and while he proved himself the superior boxer, Marquez was not fighting on level ground. Almost all of Floyd’s achievements come with some sort of equalizing qualification.

I emphasize this fight because it’s perfectly representative of how Floyd does business, that is to say, opportunistically. He casts the opponent that suits his momentary needs, whereupon circumstantial discussions (about weights, the buildup, or the fight’s timing) overshadow his work in the ring. This is unfortunate because Floyd has provided us with moments breathtaking in their mastery.

One of the most beautiful athletic sequences (4:55) I know of comes thirty seconds into the sixth round of this fight. In it, Mayweather stands in the center of the ring and pulls his neck back from the Mexican’s jab with mechanical precision. In one fluid motion he then lands a straight right hand flush on Marquez’s face as he simultaneously ducks to avoid his counter-right, which Floyd has anticipated perfectly. In doing so, Mayweather reverses his ring position to where he’s now on the other side of Marquez and can attack again. He does this with the brash precision of an athlete in complete control of himself, wonderfully amalgamating his mental and physical gifts.

Viewed in real time, rather than in slow motion, the sequence happens so quickly that it’s easily missed. Marquez doesn’t fall down, nor is he cut. Rather, he is flustered by someone whose abilities are levels above his own. Rarely is there such a disparity between elite fighters, but the difference between Marquez and Mayweather is crystallized here. It isn’t an emphatic highlight but one whose understated brilliance demands its revisiting. And its elusiveness is characteristic of Floyd’s fighting style, which operates surgically and leaves a thousand small cuts, rather than huge gashes.

This form of understated artistry, however rare, never wins widespread admiration, or else Guillermo Rigondeaux would be the most famous man in boxing. It’s an example of what Floyd can do, of how good he is, but this is only relevant to those of us who fetishize talent and it’s largely overlooked by a public that cares only about superfights between stars. Floyd can’t remain famous merely because he’s a boxing savant. A pugilist must offer personality.

Transformation and Control

In an odd way, Floyd’s talent works against him. His skills are too refined to excite the masses, but he’s too smart and instinctually safe to abandon caution in the interest of entertainment. This is problematic for a man more covetous of celebrity than boxing immortality.

Only through continual personal transformation can Floyd remain relevant, and so he recently evolved from “Money” into “TBE”, an acronym for “The Best Ever”. Floyd’s appraisal of his talent is justifiably high, but like everything he’s done since abandoning Bob Arum, his former promoter who anointed him “The Pretty Boy,” there is a calculated edge to the TBE designation. Floyd understands the necessity of manufacturing perception in the service of wealth creation better than any other boxer, and perhaps any North American athlete. Whether he’s truly the best ever is immaterial. Instead, what’s functionally important is the idea of him being the best ever, and that this idea be talked about, debated on ESPN, formally branded, and eventually, at least by some, bought.

Mayweather is more than a boxer, but a manufacturer of reality, over which he’s loath to cede control lest his star diminish. Control is perhaps the key word where Floyd is concerned, because the unprecedented degree of it that he wields is what separates him from his peers and his predecessors.

Should he be judged by the same standards we apply to past greats, who, as boxing historians point out, ‘always fought everyone’ and ‘took on all comers,’ when the reality is much foggier? What’s interesting about these appeals to the glorious past is how often great fighters were damaged by their lack of autonomy. The man often used to disprove Mayweather’s claim to be boxing’s greatest is Sugar Ray Robinson. And while his candidacy for this designation is clearly stronger, Robinson also fought on long after he should have, winning only five of his final ten fights, after which, having squandered much of his earnings and developed various health problems including Alzheimer’s, he died at 67. (In light of the recent focus on Floyd’s domestic violence issues, it can be noted that Robinson had similar allegations leveled against him by his own wife.)

Mayweather is too canny to serve the interests of the fans at the expense of his own, perhaps because of his own dramatic background. Floyd grew up in boxing, spending his childhood in gyms with his unyielding, abusive father. Floyd Mayweather Sr. was a decent professional who fought Ray Leonard, and brother Roger Mayweather was a two-time world champion. Both have been to jail (as Floyd has), both speak today with diction that’s nearly incomprehensible, and would it not be for their son and nephew, both might be without any financial stability. Having personally witnessed the ravages of prizefighting, why should Floyd do anything to endanger himself? Given the sport’s extreme physical consequences, a fighter should only be beholden to himself, since he is the sole person sustaining the trauma. Riches aren’t obtained without fan patronization, but we, the fans, aren’t the ones whose lives will be dramatically affected long after a boxer’s career ends.

Aware of boxing’s cost but intent on becoming a superstar, Floyd found himself in an untenable position. His personality had to be the centerpiece of the promotion, because his skills, by themselves, are too subtle to entice fans. By calling himself “The Best Ever,” Floyd imbues his safety-first approach with historical gravity, which simultaneously inculcates it from criticism as it encourages people to take interest.

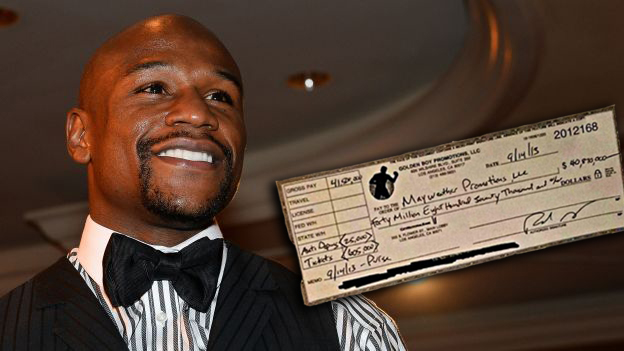

Beyond the intelligent way he’s dressed up a sometimes sedate fighting style, Floyd has shown tremendously practical, and heretofore unseen, business instincts for a boxer. Working with Leonard Ellerbe and Al Haymon, Floyd not only reaps the full benefits from his labour but also owns the means of production by way of gate and pay-per-view receipts. This unique and self-perpetuating business model has made him fabulously rich, lending further credence to the “Money Mayweather” idea. Unlike almost every other famous fighter in boxing history, Floyd controls what happens inside the ring and out of it.

As a boxing fan, I wish Floyd was less risk-averse but ultimately I have no difficulty with his caution. Workers in dangerous professions, who solely bear the physical risks and consequences, should always put themselves first. He’s plotted his career brilliantly and should be commended for his success, even if he’s a reprehensible person from whom it’s nearly impossible to identify with. But Floyd’s caution, inside the ring and out of it, has come at a price, because it’s preempted fans from forming a visceral attachment to him. Given the ceaseless negativity that surrounds him and the likelihood Floyd’s boxing career is only a means by which to expand his business empire, why does anyone continue to care?

Ugly on the Outside, Hollow at Its Core

If strong feelings are finally being directed at Floyd, it’s because more people are becoming aware of his sordid personal life. Mayweather has been cited or arrested seven times for domestic violence, and in 2012 served an 87 day jail term for a violent incident with Josie Harris, the mother of three of his children. He’s accepted no responsibility for a slew of documented incidents, some of which sound horrifying, nor has he shown contrition. Floyd is not the world’s only sinner, but to repeatedly make mistakes of this order and evince no guilt or responsibility eventually becomes unpalatable. Adjectives unrelated to boxing now bookend Floyd’s name, like “repulsive”, “misogynistic”, and most recently, on Deadspin, “monster”.

Though domestic violence is an issue that’s taken on greater prominence in the last year, boxing people have long known this about Mayweather. He’s never been harshly reprimanded by its establishment since it lacks a governing body, and because of the enormous economic windfalls his fights generate and the reality of boxing’s secondary, sleazy place in the North American sports pantheon. Not everyone has carried water for Mayweather Promotions, however. As a nice counterweight to Stephen A. Smith’s sycophantic idiocy in the SportsCenter segment he recently filmed with the boxer, a reporter from ESPN’s investigative program Outside the Lines asked Floyd if the lack of sanctions he’s faced by the Nevada State Athletic Commission sends the wrong message to victims of domestic abuse. Disturbingly, rather than answer the question, Floyd used it as an opportunity to promote the fight.

It raises a difficult, perhaps unanswerable ethical question, about whether fans should care about putting more money into the pocket of someone whose behavior is so horrid. Is it hypocritical to separate the art from the artist because we enjoy their work so much? I have no satisfactory answer, for even though I dislike Floyd, I will still watch Saturday, which will further his financial interests and embolden his self-righteousness.

He is not the first boxer to get into serious trouble. His pay-per-view ruling predecessor, Mike Tyson, went to jail for a graver crime. People will wring their hands (as I just did) but most of us will still watch because we’re too self-centered (as I am) to turn away from entertainment we love, even if it’s staged by someone we loathe. Tyson provides us with a fine comparison from which to judge Floyd, given their similarly troubled personal lives, their mutual fame derived from boxing, and their wildly diverging fighting styles. Tyson’s aggression was immediately understood, and this made him popular, but the brilliance of Mayweather’s defensive style is much less obvious.

The Floyd Mayweather phenomenon is a curious scenario, in that people care about what he’s doing even though few have a profound understanding of what exactly it is. For the occasional fans who will constitute 90 percent of Saturday’s audience, who care about the sport insofar as it’s socially expedient for them to care about it, i.e. so they can meet up with their friends to indulge, if only for a night, in an exotic interest society has momentarily deemed relevant, boxing is about spectacle and violence, and while Floyd provides some of the first he gives only a restrained version of the second. Fans knew what sort of fighter Tyson was, but the idea of Floyd Mayweather, the boxer, is amorphous. He provides no visceral thrill, and while Floyd might enter your mind, he rarely penetrates the heart. Fans observe him, but few, I suspect, feel anything for him. In the void that rests between his talent and their curiosity is only emptiness.

In a surprising admission last year, the fighter acknowledged the possibility of losing for the first time. Mayweather said that his goal was to become boxing’s smartest businessman, as if financial results were the true metric of his success. His perfect record, assumed by so many to be the jewel of his empire, is apparently subordinate to a fat bankroll. If this is true, his ambitions in boxing are starkly different from what the public thought.

This is why his fight with Pacquiao can’t be seen as part of some grand teleology, in which Floyd’s boxing journey climaxes in an inevitable confrontation with his greatest rival, without which his career would be incomplete. Rather, it might just be another timely opportunity for a man for whom business, not boxing, occupies the core of his being. Everything about Floyd Mayweather, the business mogul, is boring, because he only celebrates material acquisition, which is limited in its capacity to provide redeeming returns. He thinks his lifestyle is novel and interesting but it is redundant and tiresome. He rarely demonstrates creative thought, spewing boilerplate platitudes but failing badly whenever he’s asked something for which he doesn’t have a prepared response.

What does Saturday mean to him? What does anything beyond monetary gain mean to him? It’s impossible to say, like trying to gauge whether he cares, or is even capable of caring, about the people he’s allegedly abused. The only substantive thing about Floyd Mayweather is his boxing talent, which is more Apollonian than Dionysian, since it touches the intellect but rarely affects the heart. Everything else about him is too orchestrated to believe. What does Floyd care about? What does he feel? Maybe more importantly, what does he make us feel? I don’t know if our collective answers would gesture to anything fundamental, beyond our appreciation of his skills and our distaste for his behaviour.

Floyd shouldn’t be blamed for managing his career so cautiously; his careful approach has made a once poor man incredibly rich. But calculation comes with a price. His skills are underappreciated by the majority who buy his fights, and while he remains popular, he is so only in a superficial, quantifiable sense. But I suspect that Floyd, who is alone at the top and decidedly alone, doesn’t care. In Mayweather’s world, where money substitutes for love, he is winning outright, the playwright and protagonist of his own grand drama. Unfortunately for him, the only stories that last are the ones of substance. While he’s staged some brilliant productions, the Mayweather folio feels hollow at its core.

— Eliott McCormick

Tremendous article. It’s a great explanation of Mayweather, the person, the boxer, and the cultural phenomenon. As a devoted boxing fan, it’s always interesting seeing casual fans watch Mayweather fight. They’re always surprised that he’s small (they think he’s a heavyweight or something) and picture that he’s some sort of seek and destroy GGG-type fighter.

—

Mayweather has seemed depressed for the past couple years. Probably due to his father, Floyd’s always thought that boxing ability was the way to gain other’s approval. As his career winds down, I think he’s been disappointed by the spoils of victory. He hoped money would bring love but instead only isolation. After Floyd retires and no longer makes money for boxing, he can’t really become a public face because the domestic violence stuff. I assume he’ll become a more reclusive Michael Jordan–constantly perceiving slights and feeling anger at his inability to fight them at his old age.

Thanks very much for reading Aaron. Floyd’s had a curious career, hasn’t he? Whenever I’ve watched his fights with people unfamiliar with boxing, they almost always come away disappointed, having thought, inaccurately, they were going to witness an execution, getting instead a targeted dismantling.

When Floyd retires, I don’t think he’ll necessarily step away from the limelight unless he arrives at a psychological reconsideration of himself in which constant, one-way adulation is less important than forming positive, reciprocal relationships. That probably won’t happen. As for his reputation, it will be interesting to see whether he shows contrition once his career is over. He can behave like a hemorrhoid right now because he’s still fighting and thus has a bankable skill on which to fall back, but this default relevance ends once he steps away from the ring. Then, because he’ll have to behave nicely for us to tolerate him, we might see a gentler, more introspective Floyd Mayweather. Cynical, I know, but at least it’s consistent with the way he’s managed his whole career. Ultimately you can be forgiven for almost everything so long as you re-invent yourself as a wizened, humble person, just look at Mike Tyson. (Michael Jordan, who’s sometimes been a jerk but never acted criminally, as far as I know, apparently hasn’t learned this lesson or doesn’t care to.)

Anyway, thanks for your thoughtful response. `

Fantastic article. This why The Fight City is one of my favorite boxing sites.

Thanks a lot Scott!

What a great read. Very objective and well-written article. It gets tiring to listen to the mainstream media, i.e. ESPN and co., enable the notion that Mayweather is the greatest of all-time, without any open discussion on why that may or may not be. Granted not everyone on ESPN feels that way. I listened to Jason Whitlock’s conversation with Max Kellerman and they thoroughly dismissed Mayweather being #1 but at least discussed his great talents and where he may stand. Don’t even get me started on Stephen A. Smith.

Anyway, I don’t normally comment on boards, but I just wanted to give you my praise for an excellent article.

Thank you Alonso! Much of the boxing discussion on ESPN degenerates into cheerleading or pointless yelling matches, particularly where Stephen A. is concerned (they’re not all bad, so I don’t want to lump positive voices like Brian Campbell in with the likes of Screamin’ Stephen). Beyond those whose job it is to follow the sport, most of the other personalities don’t demonstrate much understanding of it, and groupthink takes over. Anyway, if this site can serve as a reprieve from that, I’m grateful.

Thanks for reading!

Finally! An article about Mayweather written with an accurate perspective. Well written as well I thought. Thanks a lot for this great read. Tomorrow night is fight night and perhaps one of the greatest of them all. I’m banking on Manny and some karma to see Floyd lights out!

Thanks Nicholas! I appreciate it, and I hope you enjoy the fight.

In short: we don’t like or rate Mayweather, yet we rate some of his opponents? I’m sure you have written a favourable article on a guy like Manny yet Floyd outclassed him. In his era he beat all of the top names but you’re still discrediting him. How?

No one is discrediting him. He’s a great fighter, as I took pains to illustrate in the article. The point is that he took on all names only when it was advantageous to do so. Should he be blamed for that? No, but if his career is to be understood properly, the calculating way in which it was managed must be taken into account.