He Howled and Made Horrid Faces

“They howled, and leaped, and spun, and made horrid faces; but what thrilled you was just the thought of their humanity–like yours–the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar.”

— Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

We love it when they snarl and pace the ring during introductions, absorbed by their own psychosis. We love it when they pay no heed to politesse, guiding themselves not by moral conventions but by that dark wellspring of fury, concealed somewhere inside, because it most fully oxygenates their fighting hearts. All of this we love because it imbues us with power. Nothing titillates like intimidation.

Before Roberto Duran there was Sonny Liston. Before Liston there were Jack Dempsey and Stanley Ketchel. Before and after these three there have been scores of others, some famous but most forgotten, whose reputations were forged, foremost, by their violence.

Sonny Liston was a reputed mob enforcer whose immobile gaze made virile men effete. His face didn’t ask “what the hell are you looking at” so much as it suggested an indifference towards perpetrating some back-alley horror should its wearer be transgressed. And while Liston’s fists transformed men into mush, he had technique to match his paralyzing presence. Charles Farrell describes his guile: “Far from being a one speed, forward-moving exemplar of aggression, Liston constantly thought during fights, making adjustments, using lateral movement, and taking a step back when it suited his purpose.”

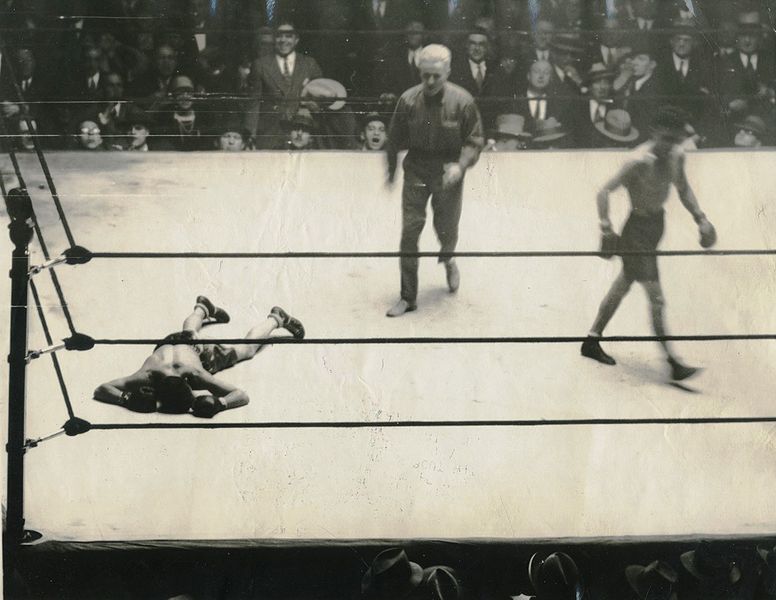

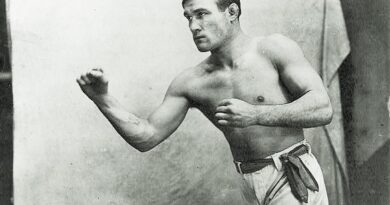

Jack Dempsey, the “Manassa Mauler”, fought like a wolverine and boasted a mythical American origin story. Handsome and brutal, Dempsey’s savage treatment of Jack Sharkey gave rise to the famed boxing adage, “protect yourself at all times.” He could veer from vulnerable to devastating, like when Luis Firpo sent him through the ropes, whereupon, with the help of several sportswriters at ringside, he lumbered back to his feet and exacted immediate revenge. No mere troglodyte, Dempsey’s skills supported his fury. As famed trainer Ray Arcel stated, “he should’ve been the only heavyweight anybody ever thought of when they thought about the greatest heavyweight champion. I mean, he had everything. He could punch, he could box. He was mean and determined.”

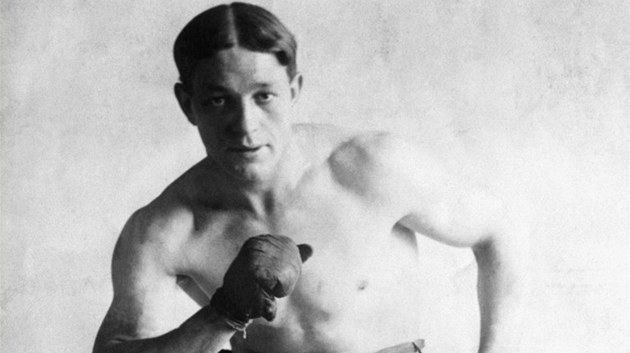

Stanley Ketchel, the psychotic Midwestern savant who presaged Floyd Mayweather as Grand Rapids’ greatest fighting export, boxed with an unquenchable bloodlust. The “Michigan Assassin” remains one of the greatest middleweights ever, a two-fisted typhoon who caroused with Jack Johnson and obtained in combat a singular thrill unavailable in life’s other legally-sanctioned activities. Murdered at 24, he didn’t live long enough to realize his potential. According to his manager, ‘Dumb’ Dan Morgan, “Ketchel was an exception to the human race. He was a savage. He would pound and rip his opponent’s eyes, nose and mouth in a clinch. He couldn’t get enough blood.”

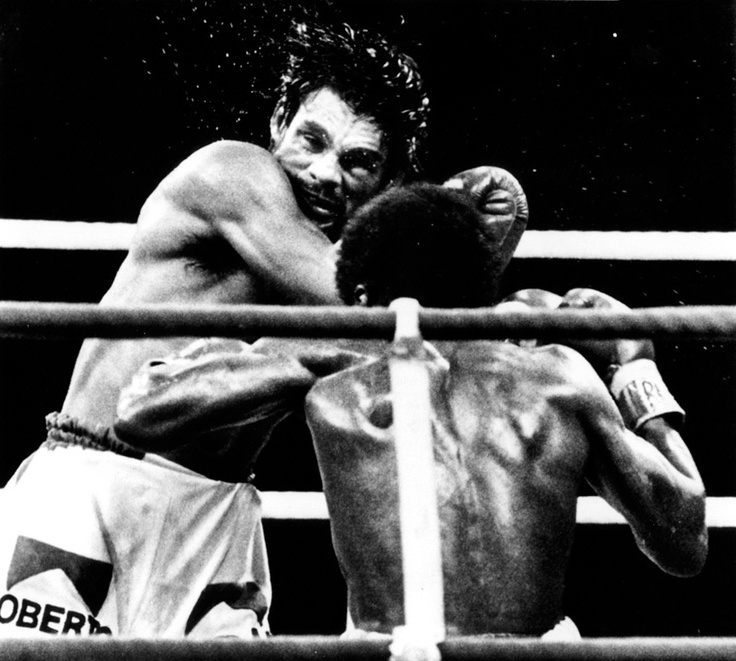

In his ferocity and power, Ketchel might be the closest approximation to Roberto Duran. The Panamanian’s reputation was substantiated by those who shared the ring with him. Sugar Ray Leonard, who Duran defeated and embarrassingly quit against, said this about his rival: “‘Manos de Piedra’, is true, Hands of Stone. Every punch, and I’m not exaggerating, every punch that he hit me with, from the body to the head, felt like bricks, stone, rocks. He knocked my teeth back. My front, my first 3 or 4 teeth, he knocked them back because he was just so possessed. He was a demon.”

Having felt his punches and stared into the black pools his eyes were said to resemble, Leonard presumably knows as much about Roberto Duran as anyone. And his words, which reinforce Duran’s otherworldliness and invoke the same demon that supposedly possesses literary geniuses and other masters of creation, lend credence to his myth.

Leonard’s words are not without ample evidence. Witness Duran’s destruction of Ken Buchanan at Madison Square Garden, in which he harnessed all of his body’s edges (elbows, knees, and the contours of his own skull) to batter and stop the Scot in the thirteenth round, cementing his reputation as a brawler who would employ every advantage to win. After the fight, United Press reported that “Ken Buchanan looked like he had been mugged in a back-alley. His left eye was cut and partially closed. There was a slit under his left eye and his groin was throbbing with pain.”

This last bit is instructive: in ways metaphorical and literal Duran attacked and battered Buchanan’s manhood. Pathologically unwilling to cede control, the ring was territory over which he had to rule. The UPI description is perfectly indicative of Duran the ideal, lending, as it does, further authority to his crotch-grabbing, macho monstrousness. But precisely because of the truth it tells, it’s also partly misleading. The passage captures Duran’s savagery but pays no heed to his technique.

Why is the savagery of Manos de Piedra so attractive? Because by reveling in his animalism we place ourselves on the right side of danger. We gawk at its awesomeness and see it as a logical extension of ourselves had we only the temerity and tools to act out our aggression. But Duran, the most rhythmic of fighters, was more than an elementary brawler. Like Liston, or Dempsey, or even Ketchel, had it not been for his skills, “Hands of Stone” would have merely been a tornado—furious, awesome, but ultimately finite—who would have expired quietly on one of boxing’s remote plains, and thus far away from the lights that mint its stars.

And Duran was skilled, prodigiously so. All you have to do is impose a critical eye on his biggest wins to see his craft and intelligence. Watch as he bobs both ways, dipping his shoulder to throw an overhand right with his distinctive lunge, twisting his head away when his opponent tries to counter. He could batter opponents with both hands, mixing hooks with uppercuts and bruising power shots, treading laterally with the dexterity of a Latino man for whom dancing is a cultural endowment. And while his power is repeatedly invoked, Duran was as cagey as he was brutal, blessed with impeccable timing and the requisite grace to slip his left hand through Ray Leonard’s guard the second an avenue became available. Known primarily for his violence, there was always artful calculation at work.

Angelo Dundee knew that ‘Hands of Stone’ was more than a meat-fisted belligerent: “One gets the impression of Duran that he’s a tough, rough brawler who just wades in and ducks nothing. But all you have to do is look at his face to see that’s nonsense. He’s not marked up. He does a lot of cute things in there.” Dundee saw Duran for what he truly was: a skilled technician who employed brawn and brains in equal measure.

As fans we interact with image and ideas, and often ignore reality as we search for ourselves in those we idolize but this can lead to simplistic interpretations. Boxing is not a gladiatorial contest, insofar as that implies nothing more than a crude and brutal contest of wills. Though he was, unquestionably, a tough guy, Roberto Duran was more than the archetype he came to inhabit. He howled and made horrid faces and beat his chest, but “Hands of Stone” was more virtuoso than monster. He inhabited that rare space where intellect, physicality, and courage coalesce at the highest level. His genius may have been powered by a demon, but his art bore an erudite grace that was unmistakably human. — Eliott McCormick