April 14, 1979: Galindez vs Rossman II

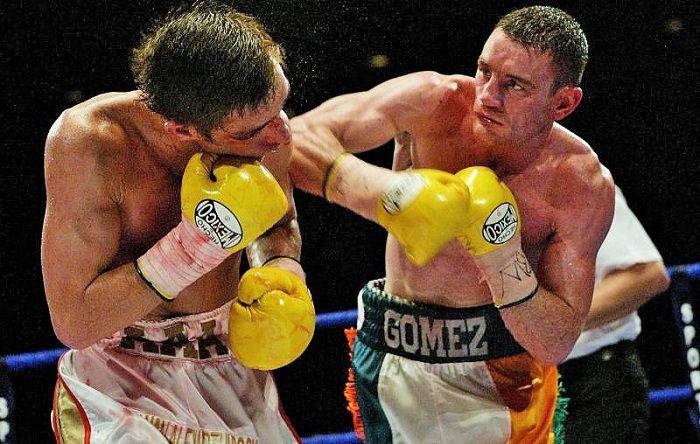

The Hispanic code of “machismo” is a harsh one. Pain, weakness or humility do not exist for the true “macho man” who concedes nothing, will never admit defeat or failure. In the 1970s, such men wreaked havoc in the world of professional prizefighting. The list is led by Roberto Duran and Carlos Monzon, but that famous and formidable pair were far from alone. Ruben Olivares, Wilfredo Gomez, Rafael Limon, Carlos Zarate — all tough, proud, Latino boxers, all world champions. But perhaps none better exemplified the stubborn spirit of the true “macho” warrior than Argentina’s Victor Galindez.

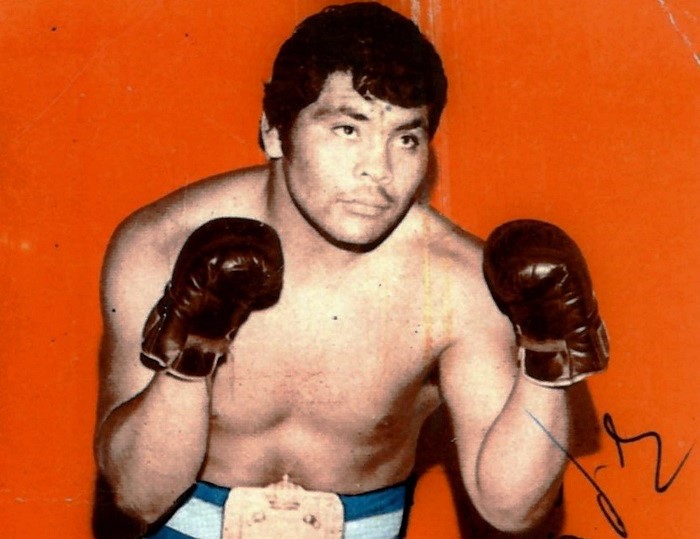

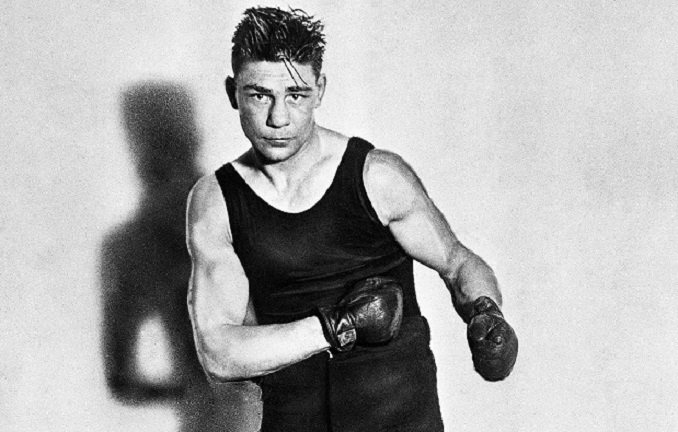

Not particularly powerful, Galindez relied on aggressiveness, brute strength and excellent counter-punching skills to best his opponents. No one questioned his toughness or his courage. Undefeated in 23 fights before seizing a world title in 1974, he then won another nineteen straight. In all, he had gone almost seven years without a loss when he defended against a young American contender named Mike Rossman on the undercard of the rematch between Muhammad Ali and Leon Spinks in September of 1978. Few gave Rossman a chance to dethrone the champion, with most pundits only speculating as to how long the bout might last before Galindez notched another victory.

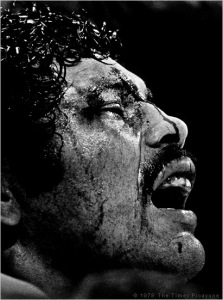

But to everyone’s surprise, Rossman soundly defeated the champion. Showing no fear of the now legendary veteran, the challenger elected to fight toe-to-toe, his straighter, sharper punches opening deep cuts over the champion’s eyes. As the rounds passed Rossman’s confidence only grew and by the late going he was flat-out dominating his bloodied and battered opponent. In round thirteen, an exhausted Galindez was being pummeled on the ropes when the referee stepped in and brought a halt to the one-sided thrashing.

Such is the harsh code of machismo that a few weeks later Galindez appeared at a boxing card in Buenos Aires and the fans booed him mercilessly. Machismo also demanded that Galindez give Rossman no credit for his win. “I had been sick,” said the ex-champion before the rematch. “I had marital problems. I weighed 190 pounds and I had to starve. I wasn’t myself as a fighter.”

After Rossman notched a routine title defense, Galindez vs Rossman II, complete with live national television coverage, took place in Las Vegas on March 3rd. Except it didn’t. Literally ten minutes before the contest was slated to start, Galindez packed up his bags, strode out of his dressing room and left the building. “I don’t need the money,” he growled as he stormed out of the arena.

The reason? The Argentinian challenger and his people had insisted on “neutral” judges, i.e. Latin American, and when the Nevada commission refused to comply, Galindez refused to fight. Again, macho principles made backing down, even under the most intense pressure, unthinkable. Bob Arum and ABC television were left to pick up the pieces.

The rematch was scheduled for April 14th, this time back in New Orleans, and this time Galindez, after getting the officials he wanted, made his way to the ring without incident. And this time, the ex-champion had trained with zeal and, in contrast to the first fight, was in superb condition.

The opening rounds were tightly competitive, both boxing respectfully, Rossman’s hand-speed and straighter punches giving him a slight edge, but then the turning point came in the fourth. Rossman connected with some excellent right hands and appeared to be gaining control, but his eagerness to trade brought him into firing range for the Argentine. At the end of the round Galindez connected with a thunderous left hook-uppercut combination that hurt the defending champion badly. When the challenger kept punching after the bell, Andy Rossman, Mike’s brother, stormed the ring and Galindez threw a couple shots his way as both corners threatened to turn the affair into a free-for-all.

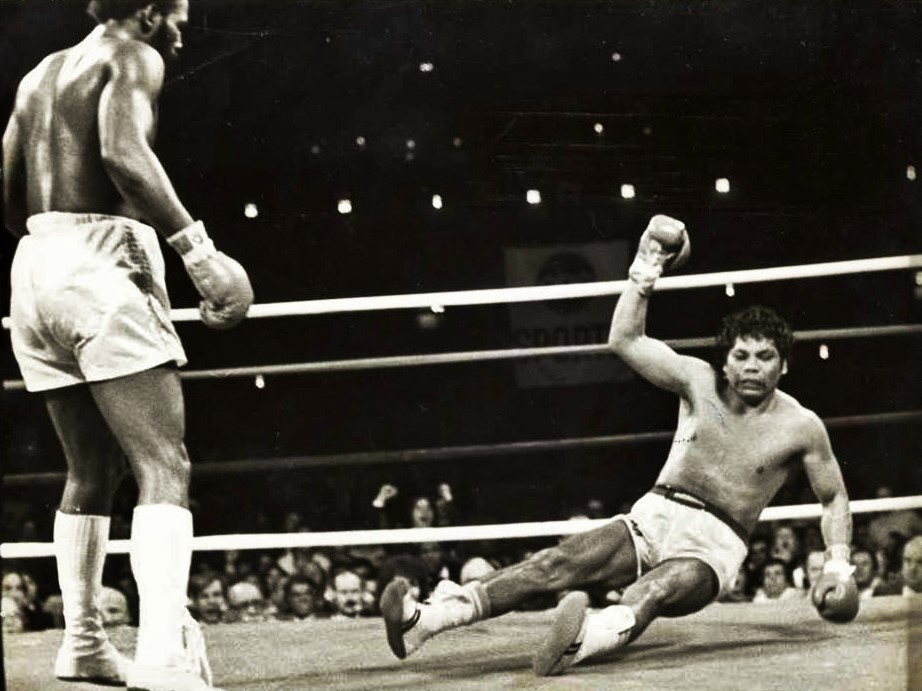

That didn’t help Mike any, and things soon enough went from bad to worse for Rossman. At some point he scored with a right to the top of the challenger’s head and fractured his hand. Galindez, attacking with more fury and effectiveness than he ever showed back in September, now took over, mauling Rossman on the ropes and clubbing him with both fists. Unlike the first fight, Victor did not tire and cuts were never a factor. In desperation, at the end of round nine Rossman blatantly butted Galindez. It would be his final telling blow of the match as immediately upon taking his stool he raised his right hand and told his corner, “I can’t stand the pain.” The referee was summoned and the contest was brought to an end.

The moment the fight was officially halted Galindez attempted to charge across the ring, not to show sportsmanship and pay respects to a fallen opponent, but instead to taunt Rossman, shouting invective and gesturing his contempt. Ever the macho man, the champion conceded no regard or esteem for his former conqueror, quite the contrary. Quitting, it must be remembered, is the cardinal sin of the macho code, as Roberto Duran would learn the following year.

“I’ll never fight him again,” vowed the first man to ever regain a light heavyweight world crown. “He’s a chicken, a coward. I’ll never give him a rematch.” When it was pointed out that Rossman gave him a second chance, Galindez dismissed the argument. “I got a rematch because I deserved it. I won’t give him one, because he doesn’t deserve it.”

True to his word, Galindez instead fought Marvin Johnson. He lost by a knockout in the eleventh round, and then lost again before being forced to retire due to detached retinas in both eyes. His boxing career finished, what could a macho man do but become a race car driver? In October of 1980 and in his very first race, Argentina’s famous Turismo Carretera, Galindez and his driving partner suffered a breakdown and pulled over. Minutes later another car slammed into them, killing both men. Victor Galindez was 31-years-old. — Michael Carbert

Victor Galindez is revered in my country (South Africa), having defended his championship here four times (against Pierre Fourie twice, Kosie Smith and – in a fight for the ages – Richie Kates). Galindez – Kates rivals Moore – Durelle as the greatest LH title fights of all time, IMO.

Galindez, who stood five-nine, had frequent problems reducing to 175 pounds, but was a steel-chinned, relentless counter-puncher whose volleys compensated for his dearth of power. Until Marvin Johnson dropped him and broke his jaw in 1979. “Vicious Victor” had never been floored or stopped. Always a macho man, Galindez turned to stock car racing after his career ended and he was killed in the pits of his first race in 1980 when another driver struck him. Galindez was eight days short of his thirty-second birthday. RIP, Victor, you were GREAT!