Fist Of The Reich

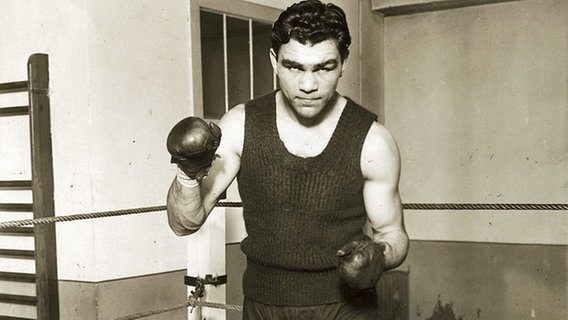

Max Schmeling was the first German-born world heavyweight champion and the only boxer to defeat Joe Louis in “The Brown Bomber’s” prime. A sporting hero to the German people, he risked his life during World War II, first in combat as a German paratrooper and then through his decision to protect the lives of two Jewish children from the Gestapo in 1938. Decades later he helped support Louis when his former opponent was suffering from financial ruin and ill health. His life, which unfolded during one of humanity’s worst periods and reflected the dynamism of its age, is one deserving of magisterial cinematic treatment. Unfortunately, Max Schmeling: Fist of the Reich treats his story with the grace of a Panzer blast.

Poorly acted, with a simplistic, timeline-like plot, the film’s insistence on being comprehensive prevents any genuine exploration of Schmeling’s personality or of the tumultuous era in which his boxing career peaked. It is as if the director took a checklist culled from the boxer’s Wikipedia page and then filmed corresponding scenes to ensure no event went undocumented. The result is a hackneyed movie whose most reliable performer is cliché.

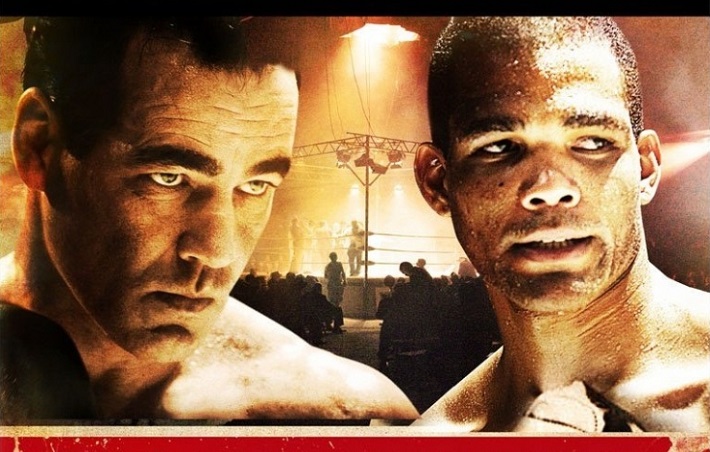

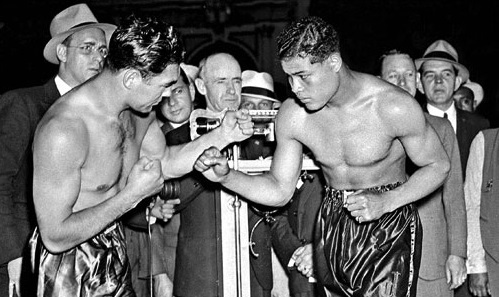

Directed by Uwe Boll, who has been described as the Ed Wood of the 21st century (and whose Wikipedia page, a must-read, says that he’s challenged critics of his ‘art’ to real boxing matches), and told in German with English subtitles, Fist of the Reich follows Schmeling from his first fight in the United States with Jack Sharkey through his win over Joe Louis, induction into the German Army, and eventually to his retirement. The tale is told by Schmeling himself when, as a wounded soldier stationed in Crete, he’s ordered to escort a British POW back to main camp. The benevolent former champion takes pity on his prisoner, freeing him before he tells him his story. What ensues is a Power Point presentation of a famous person’s life.

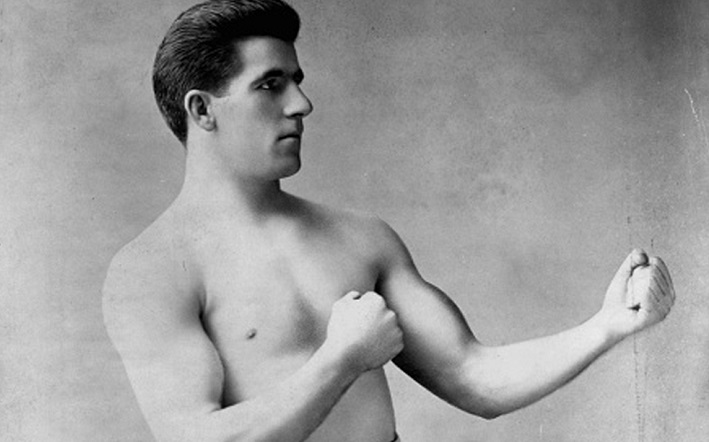

The salient details are all covered. Schmeling wins the heavyweight title when he is the victim of a low blow from Sharkey. The German boxing public doesn’t believe he’s a worthy champion, but he eventually wins their respect before losing his title to Sharkey by controversial decision. He marries a prominent actress; takes on the unconquerable Louis and beats him; sticks by his discriminated Jewish manager; separates himself from the toxic spectre of Nazism, and then, in one of the biggest fights of all time, loses to Louis in their rematch. Schmeling then retreats into an idyllic countryside existence with his wife, gets drafted and is wounded in battle, and then embarks on a ring comeback.

This narrative would be fine if the film at least attempted to probe beneath the surface of the events it documents. Schmeling, played mechanically by German boxer Henry Maske, is presented free of nuance: honorable, reserved, and unwavering in matters of conscience, he is less a human being than he is an archetype, the sort of hero you might expect to find in a dramatic film financed by the military. Schmeling’s real legacy is a commendable one, but the movie fails to investigate the source of his antipathy towards Nazism. It simply expects you to believe that he was above the prejudices of his time because he is less a person than a monosyllabic, pan-humanist ideal.

The film’s title suggests a dramatic tension between Schmeling and the Nazi hierarchy, but this is also treated lightly. Several times he meets with the Nazi Minister of Sport to assert his independence from the government’s political agenda; this isn’t really a central conflict in the film, but a subplot in a meandering narrative which never reaches any kind of meaningful resolution.

The lead actor’s wooden performance is the film’s most obvious shortcoming. A former IBF light-heavyweight champion, Maske is ill-suited to dramatic acting. His handsome face is largely immobile throughout the movie, communicating minimal human emotion, and it’s rare that he has any sustained dialogue. Perhaps this is why the action-obsessed Boll includes so many different scenes, because their sheer volume prevents the director from having to rely on protracted verbal exchanges to create tension. If this is the case, it’s an ineffective tactic, for it prevents engagement with the film at a serious level. Conversely, serious engagement might not be the point, and if this is true then the title’s evocation of Schmeling as an unwilling tool of absolute evil is a cheap ploy to lend gravitas to a film with only flimsy pretences to seriousness.

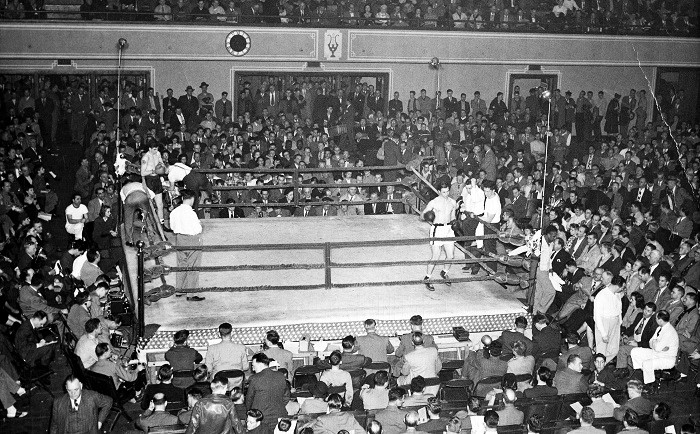

Most surprising about the The Fist of the Reich is how feeble its boxing scenes are. If nothing else, Maske should at least be able to pantomime punches, but he looks stiff and unnatural. The film doesn’t even attempt to capture the magnitude of the Yankee Stadium setting for the Louis fights and each time it looks as if they’re boxing in a warehouse on a movie set. At times the production value is simply ludicrous. When Schmeling fights an exhibition match in Germany after his win over Louis, there is a computer-generated shot of an arena crowd, and it looks like something from a decades-old video game.

It’s impossible to recommend Fist of the Reich except to devotees of the worst cinema. Anyone genuinely interested in the life of Max Schmeling would be far better served to consult the various books written about his boxing career and his bouts with Louis, or his autobiography, published in 1994. Fist of the Reich only elicits wonder due to the fact it was ever released. I have no idea how Schmeling felt about movies, but even the most generous critic would find Fist punchless. – Eliott McCormick