Brandon Brewer And The Rise Of The Plaid Army

If you ever feel anxious about the quality or abundance of Canadian forests, drive through the bucolic hills that populate the province of New Brunswick. The perfectly paved highways, void of the automotive insanity that haunts metropolises like Montreal, will take you through a serene landscape with rolling elevations, mighty rivers, and a rugged coastline covered in trees, enough to make you feel completely engulfed. But while New Brunswick indeed relies on its forestry industry, the province has of late become known for a new sort of lumberjack: undefeated junior middleweight contender Brandon “L-Jack” Brewer and his Plaid Army.

Brewer (20-0-1, 11 KOs) hails from Nackawic near the shores of the St. John River and home, literally, to the world’s largest axe, which weighs 55 tons, stands 15 metres high, and boasts a seven metre axe head. Multiple Brewers have worked in forestry and Brandon exudes a fierce sense of loyalty and pride when speaking of his home, even when acknowledging the economic hardship that has wracked swaths of New Brunswick.

Getting ready to chop down that 19th tree….. We get the best out of ourselves when we stay true to ourselves and continue to remind ourself of where and what we come from. Photo credit @maghood #plaidarmy #work #axe #choppintrees #undefeated #boxing #adidas #canadian #stihl #woodsmen #outdoors #beardsofinstagram. #beards #tattoos #canada #newbrunswick #maritimes #success #entrepreneur #dedication #determination

For an undefeated contender currently in his athletic prime who got a late start in boxing, the easy, and ultimately ignorant queries, would be: why not relocate to a boxing hotbed like Montreal where opportunities and elite sparring abound? Why not use what you’ve accomplished as a professional and as a boxing promoter as a springboard, instead of planting even deeper roots in Fredericton? For Brewer, however, there are myriad reasons for committing to New Brunswick. When you peel back the layers of his story and his struggle to reach the precipice of the elite level, the reply to any of these questions becomes: why would he abandon what he’s created from scratch?

To understand where Brandon Brewer currently finds himself, both in boxing and in life, it’s important to know that he nearly threw it all away. A multi-sport star in high school, Brewer enrolled at the University of New Brunswick where he was working towards an engineering degree. He was also a reservist in the Canadian Forces. But Brewer admits that he possessed a rebellious streak, and he brings up having to pay a plethora of fines after getting arrested on multiple occasions for fighting in public. Eventually things got worse, and that’s what led Brewer to a boxing gym.

“It was a time when I was at a crossroads in my life,” Brewer says of this difficult period. “I quit university, I quit the military, I lost my license for drinking and driving, and then I got alcohol poisoning and got ulcers. So, I really had some time to sit and think about what I wanted in life. And I finally came to the conclusion that I wanted to box.”

Because Brewer had lost his license, he’d get his road work in by running to the boxing club. With his commute now part of his training, the sport quickly consumed Brewer. He describes spending hours upon hours watching fights on YouTube, studying the human form and movement, and visualizing what he wanted to attain. Brewer firmly believes that boxing chooses people, not the other way around, and his fixation on the sweet science quickly morphed into an outright addiction. Whether it was the dead of winter or during blistering summer months, Brewer would put insomnia to use in those early days, jogging to the illuminated parking lot of Fredericton’s Nashwaaksis Field House, where he’d shadow box all night to avoid disturbing members of his household. Due to his late start in boxing, Brewer understood that a tireless, bordering on obsessive, work ethic was his only means of survival.

If fans or pundits are going to follow the early career of a prizefighter, it will generally be of those who enter the pro ranks riding the momentum of multiple amateur triumphs in international competition or the Olympics. By contrast, after an amateur career comprised of just nine fights, Brandon Brewer turned pro at age 26 with no fanfare or backing of any kind. But he needed money, and securing bouts in the unpaid ranks proved maddening. In 2011, Brewer simply threw his hat in the ring for an upcoming professional card in Moncton.

Despite jumping out to a 4-0-1 record, Brewer was struggling. The draw on his record — its only blemish and later avenged — came against middleweight contender and Montreal brawler Francis Lafreniere. The day before weighing-in for the fight, Brewer roofed a house and he entered the ring exhausted, which proved an eye-opening experience. It was clear: he needed to find a way to be a full-time professional athlete.

Brewer quit his job with the understanding that he had a $900 unemployment claim coming his way, only to get stonewalled by EI bureaucracy. It was February at the time, a particularly punishing and isolating month in the Maritimes, and Brewer was living in an old taekwondo dojo without heat or hot water, the office serving as his bedroom. His 1997 Mazda Protege had a hole in its gas tank, and he was down to his last $20. To fight the biting cold, Brewer would either sleep next to his Rottweiler or hit the dojo’s double-end bag all night.

“I took a pen and paper and I said, ‘Okay, I need to find some sponsors,'” Brewer recalls. “Because at this point I was 4-0-1. So I mapped out all the spots and places locally that I could ask for sponsorship money.”

Of his dwindling funds, $10 went to gas, which Brewer knew would only take him so far given the leaking tank. The remaining money was used to buy rice and ketchup, the indulgence of the condiment meant to please his dog’s palate. Brewer’s first stop was a local skateboard shop, and he came away with $100, more money for food and gas. His next pitch netted him $500. In order to present his case to local businesses, Brewer had bought a binder and bristol board from an office supplies store to make a portfolio of his newspaper clippings, a boxing CV of sorts. Bolstered by this encouraging enthusiasm and support, Brewer, now immersed in the struggles of the starving athlete, had gotten his head above water, even if he was still treading.

If you scour Brandon Brewer’s professional ledger, there’s a curious stretch of four fights that took place in the United States — two in Maine, and one each in West Virginia and North Carolina — against opponents with records of 2-19-2, 1-6, 4-27-2, and 3-14. Prior to this U.S. sojourn, which at an uncritical glance looks like mere record padding, Brewer had defeated journeyman Paul Bzdel for the Canada Professional Boxing Council super welterweight title. So what was a Canadian champion doing fighting such meagre opposition? The answer is both startling and revealing.

Moments before I stand tall with my Army, and we march onward to victory…..photo credit @maghood #plaidarmy #teamljack #march #victory #lumberjack #undefeated #stihl #husqvarna #timberland #boxing #canadian #canada #everlast #grantboxing #reebok #adidas #newbrunswick #nyc #vegas #california

After defeating Bzdel, Brewer knew it would be difficult for promoters in Moncton and Shediac, the two cities where he’d had his first nine fights, to arrange for opponents. Still a relative novice in terms of actual boxing experience, Brewer was desperate for rounds and the exposure to live combat. So, he decided to gamble on himself.

“I took some of the money I made in my Canadian title fight against Paul Bzdel, and I contacted a promoter down in Maine and basically said I’d fight for free and I’d put money towards my opponent’s purse if they could find me an opponent.”

After struggling to pay his electricity bill, Brandon Brewer twice paid $1,000 out of pocket just so he could stay busy. His phone wasn’t ringing with offers, and he was mired in the wasteland of promotional free agency. As an unknown from New Brunswick with no meaningful amateur credentials to brandish, he realized he had to do everything on his own at the career stage where a bluechip prospect would be eyeing matches on national television. Despite this quixotic string of fights, a turning point came in the form of Toronto promoter Lee Baxter reaching out and inviting Brewer down to Ontario to spar with Samuel Vargas. Brewer assessed his situation, fixed his hobbling vehicle, and drove all the way to Toronto. Two days later he was in camp with Vargas, where he raised eyebrows to the extent that he worked with Baxter for his next handful of fights.

Although Brewer hit his stride working with Baxter, including claiming the WBA-NABA Canada super welterweight title and generally fighting a better class of opposition, two things were needling him: the ban on professional boxing in Fredericton, and his inability to figure out the logistics to train in Montreal for an extended period. Brewer talks about the incessant queries he’d be bombarded with regarding an intensive camp in Canada’s boxing capital, his frustration growing when those questioning his inability to get there clearly failed to realize, or even acknowledge, the organizational and financial hurdles standing in the way of such an undertaking, especially for a fighter in his precarious position. While Montreal remained an important goal, Brewer decided to take care of some business at home first.

Brewer started L-Jack Promotions with an aim to bring world class boxing to New Brunswick and get the ban on professional prizefighting lifted in Fredericton, the provincial capital that is simultaneously culturally vibrant and home to two universities, but also stuffy and white-collar like any government city. When Brewer founded his promotional outfit, there wasn’t even a provincial boxing commission in New Brunswick. While Shediac and Moncton had local commissions, a sanctioned boxing match was outright illegal in Fredericton. When New Brunswick’s government swung to a Liberal majority in 2014, Brewer saw an opening to advocate for establishing a provincial commission. With the help of Brewer, and other key parties, tirelessly badgering MLAs, the province’s power structures eventually bought in and made it happen. But there was a catch: even with that framework in place, a letter of consent had to be obtained from any municipality where you wanted to host a fight card; all major cities in New Brunswick were on board, except for Fredericton.

Fredericton Tourism was Brandon Brewer’s first lobbying stop, and although professional boxing providing an economic boon for the city was a straightforward and viable sales pitch, Brewer sensed they were dawdling. And so, just as he had when literally giving away his fight purses to box regularly, Brewer sprung into action. He marshalled supporters and the local CTV news station, who proved receptive to his struggle. The province’s top boxer being denied the right to fight in his hometown was indeed a compelling story. Shortly after a passionate interview on the steps of Fredericton’s city hall, the boxing ban was lifted.

“I knew I was under an intense microscope,” Brewer says when speaking of organizing, promoting, and headlining his first fight card in Fredericton. “And I knew that this being boxing, if anything went wrong they were going to be very quick to stereotype. So I knew it had to be done professionally on every single level – right from the liquor sales, to the ticketing, to the promotion, to the fights, to the sportsmanship, to the weigh-ins, to everything.”

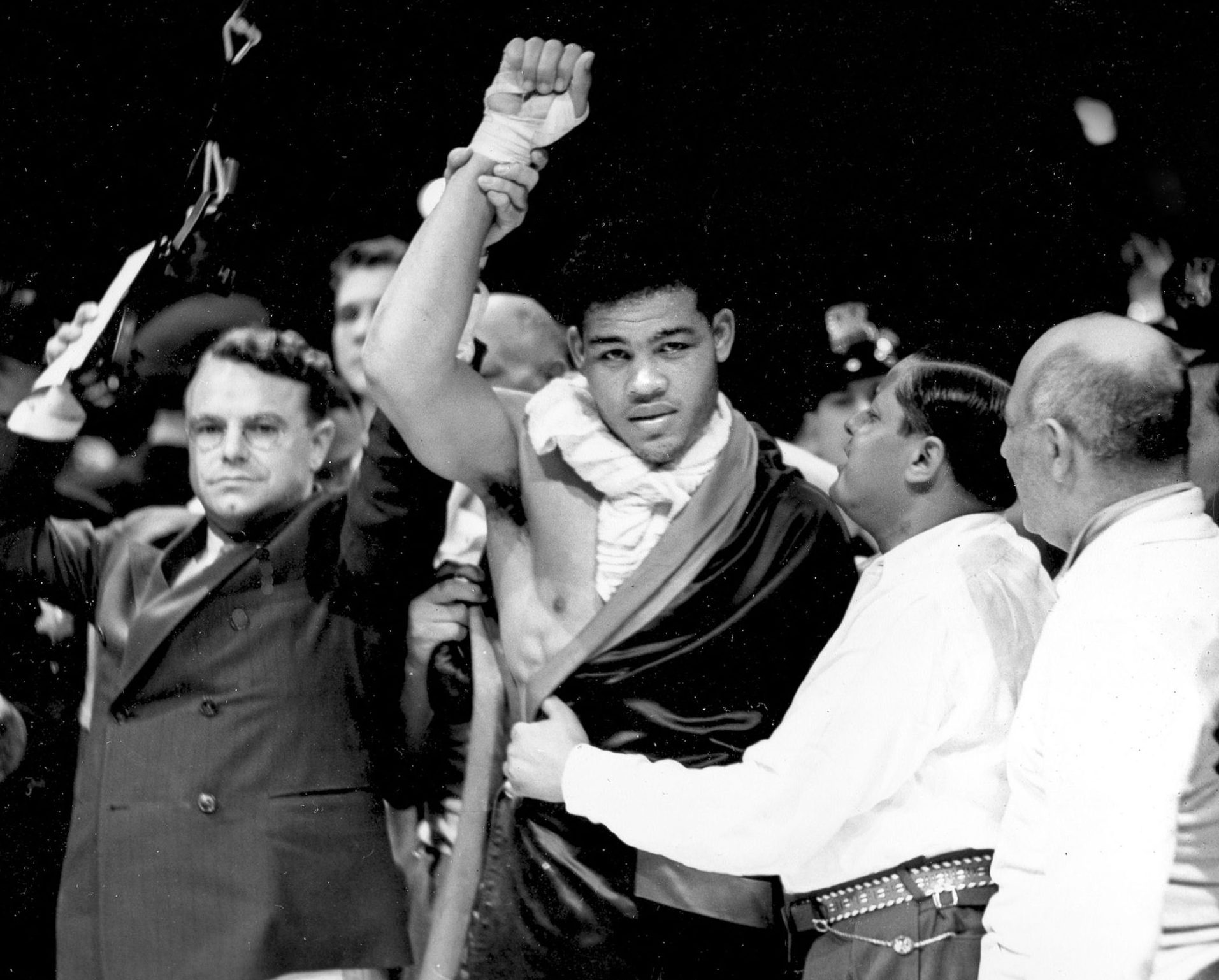

On May 14, 2016, Brandon Brewer headlined a professional boxing card at Fredericton’s Aitken Centre, home of the University of New Brunswick’s powerhouse Varsity Reds hockey team. Brewer stopped Diego Adrian Marocchi in three rounds, and the night was a surreal success. 3,500 raucous fans, including legions from Brewer’s Plaid Army, jammed into the arena, the fight serving as the centrepiece of an entire weekend of pre- and post-fight events, which included a country music concert at the city’s Exhibition Grounds attended by 1,500 euphoric supporters, who were shuttled from the fight to the show by buses that Brewer chartered.

The event provided a spark for an embattled province mired in economic hardship. But since that first Fredericton fight, Brewer has been active in the community, speaking at three high schools, three middle schools, and two elementary schools about his life and career. He’s also taught boxing basics and seen interest in the sport grow in a new generation of Fredericton athletes.

“Our province, the economy isn’t the greatest,” Brewer admits. “I don’t want to say it’s a down-and-out province, but the energy isn’t that high. My vision was to not only have a good boxing event, but to create an atmosphere – create an energy – that woke up not only Fredericton, but woke up the province.”

That he did, and Brewer is willing to wager that 3,500 Maritimers bring the passion to drown out an equal number of supporters from anywhere else in the world.

“People in the Maritimes in general, they’re just so passionate, so loyal, and they’re very proud,” Brewer says. “The energy walking out was just insane. Honestly, walking out through that crowd was probably the most surreal feeling that I’ve ever had in my entire life. I knew it was going to be big and knew people were going to be excited, but I did not know the magnitude of it. I did not know the level of energy that I was walking out to.”

Chopping trees Photo credit Steve Brewster #choppintrees #undefeated #ljack #canada #plaidarmy #boxing #trees #rivalboxing #ireland #vegas #motivation #nyc #inspiration #hardwork #plaid #ljackpromotions #reebok

The cohort responsible for Brandon Brewer’s enviable fan support, popularity, and community activism is the aforementioned Plaid Army. In studying boxing both in and out of the ring, Brewer came to the sobering realization that survival in the professional racket boils down to selling tickets, and that whereas amateur boxing is a sport, the paid ranks is very much a business. Given the way Brewer’s fanbase has multiplied, it’s clear that he has a preternatural gift for marketing. Brewer recounts, with a smirk and chuckle, how his entire closet growing up was plaid. With Brewer’s lumberjack lineage, the Nackawic axe, and the need to set himself apart from other fighters, he saw the potential to foster a sense of camaraderie and positivity amongst his supporters, to create a community that views attending his fights as a type of family reunion.

“I needed to let the promoters know who my fans were, so I told them all to wear plaid and grow their beards out,” Brewer recalls about the inception of the Plaid Army. “The first time I did that was when I fought Paul Bzdel for the Canadian championship. And I bet you 90 percent of the people were in plaid with beards. Even women and children had tape-on beards.”

While the Plaid Army is undoubtedly a galvanizing force for Brewer, its influence extends beyond boxing. Brewer and the Plaid Army have organized fundraisers for Fredericton’s homeless shelter, as well as Brandon’s former elementary school, which had cancelled its breakfast program. The Plaid Army stepped up with a breakfast-by-donation drive and raised $2,000. When recounting these charitable endeavours, Brewer is careful to highlight the Plaid Army’s unacknowledged work, asserting that he’s the “lucky one” who gets to deliver the money or be the proverbial ribbon-cutter in their name, a role he treats with solemnity. And even though Brewer is able to profit from Plaid Army merchandise, he looks for ways to give back. Over the past two years he’s donated percentages of t-shirt sales to the homeless shelter and Fredericton’s food bank, a reminder that beyond boxing, Brewer has a genuine commitment to community building.

Extremely proud to represent The Plaid Army, who raised $2000 for the breakfast program at my old school, The Nackawic Elementary. My fans are some of the most caring, loyal, helpful ppl in the world. I am truly blessed. #plaidarmy #teamljack #breakfastprogram #fundraiser #breakfast #boxing #fanbase #Canada #newbrunswick #nackawic #canadian #plaid #army #loyal #fans #weretakingover

On May 27, Brandon Brewer will fight for the third consecutive time at Fredericton’s Aitken Centre on the UNB campus. His opponent will be King Davidson (18-2, 12 KOs), who sports a reported 175-5 amateur record and won a bronze medal at the 2002 Commonwealth Games. By the time the bell sounds for round one, Brewer will be ending a seven-month layoff and kicking off what could be a career-defining 2017 campaign. Which brings us to Montreal, and Brewer’s four-year odyssey to arrive in Canada’s boxing mecca.

When a fighter like Brandon Brewer is somewhat relegated to the margins of elite prizefighting in Canada and can only watch from afar Montreal-based boxers, who enjoy solid promotional backing and major media attention, it’s easy to place one’s contemporaries on a pedestal. Brewer arrived in Montreal in January and spent a month training and sparring at the city’s toughest gyms and with some of its best fighters. His intensive training camp proved transformative and allowed Brewer to gather the empirical evidence needed to confirm that he has “world class” talent. It also bred a new degree of confidence in his overall athletic ability.

“The major improvement I’ve found has been mental,” Brewer says. “It’s confidence in the fact of where my skills stand compared to everybody else. You know, when you’re training in the gym, in a basement, with nobody there – with your dog there chewing on a bone – it’s hard to put yourself on that pedestal with the guys who are on TV, the guys who are fighting for world titles, and the guys who are touted to be future world champs. It’s hard to put yourself beside them, or above them, or near them.”

During his Montreal camp, Brewer spent time at the Grant Brothers gym and Sherbatov MMA, but he made Donnybrook Boxing Club — home to Canadian super middleweight champion Shakeel Phinn and former fighter, top trainer, and Fredericton native Ian MacKillop — his base of operations.

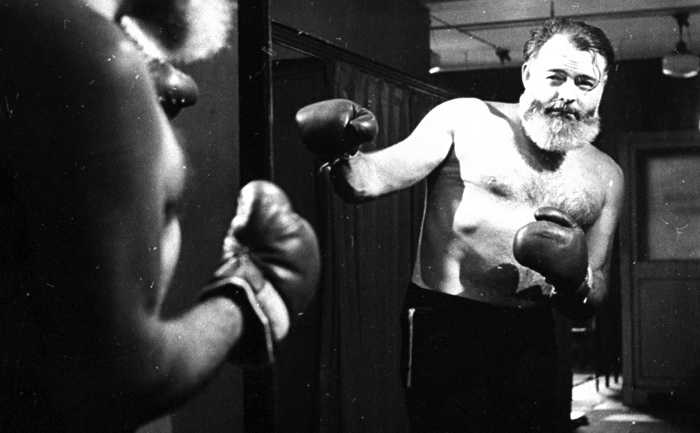

It makes sense that Brewer would gravitate to Donnybrook given his relationship with MacKillop, who he’s admired since first lacing up gloves. Brewer describes seeing a picture of MacKillop holding his IBO Inter-Continental and IBF Australasian super welterweight titles on the wall of his former Fredericton gym, which inspired him to attain that same level of success in boxing. Although Brewer hadn’t yet met MacKillop during his early apprenticeship in the sweet science, he’d heard nothing but glowing compliments about the man who had been in training camps with Vernon Forrest, Shane Mosley and James Toney, and who had also worked with legendary trainer Freddie Roach. A storehouse of pugilistic knowledge with myriad experiences to offer, MacKillop willingly and consistently shared sage life and career advice with Brewer.

“I’ve always kind of looked up to him,” Brewer says. “Ian and I are very similar in a lot of ways, and I try to mould myself – not even as an athlete, but as an individual – after him because he’s such a good guy and has such a respected name.”

But it wasn’t just MacKillop’s generosity and sagacity that Brewer benefited from while he was in Montreal. Brewer sparred with the likes of Shakeel Phinn, 2016 French Olympian Christian M’Billi (3-0, 3 KOs), Bruno Bredicean (8-0, 3 KOs), Francy Ntetu (16-1, 3 KOs), and former rival — and now friend — Francis Lafreniere (15-5-2, 8 KOs). He was even going to spar David Lemieux, but that was nixed given that Brewer hardly has the style to mimic Curtis Stevens, who Lemieux would go on to ice in a leading Knockout of the Year contender. Brewer found each gym he visited to be accommodating and respectful, and he feels the city’s boxing community exudes sincere solidarity. “It’s going to be very easy to come back here,” Brewer says.

Of all the heated sparring sessions Brandon Brewer engaged in, few were more intense than the gruelling rounds shared with Lafreniere, who actually provides an interesting counterpoint to Brewer’s development since their two bouts as novice pros. Lafreniere, who has always been matched tough, got off to a rocky 3-5-2 start in the paid ranks. His transformation since then, however, has been nothing short of sensational. Currently on a 12-0 run that has seen him capture the Canadian, IBF International, and WBO NABO middleweight titles, he has firmly established himself as a popular and thrilling combatant in the Arturo Gatti mould, his war of attrition victory over Renan St. Juste serving as an unforgettable example of breathtaking violence and resolve.

As Lafreniere has discovered his pugilistic identity and continues to close in on world rankings, Brewer has methodically crafted his rise in New Brunswick with a different kind of fanfare and day-to-day boxing existence. When they met again in Montreal to spar, both had evolved into entirely different fighters, rendering their sessions just as competitive, albeit more sophisticated. Brewer, looking to shore up weaknesses in his craft, opted to meet Lafreniere toe-to-toe on the inside, a daunting task for any fighter. But given that Brewer is most comfortable using his speed and athleticism to box from range, working with Lafreniere presented a unique opportunity to test the extent of his willpower and hone the subtleties of in-fighting. When speaking with Brewer after Marie-Eve Dicaire’s win at the Casino in early February, he laughingly pointed to a light shiner around one of his eyes as evidence of how much he was learning from his former foe’s diametrically opposed approach to boxing.

“Boxing’s a lot like dancing,” Brewer says. “And I know Francis as a dance partner, and he knows me as a dance partner. So we work extremely well together. I know some of his flaws, and he knows where he can catch me. It’s great to see how he’s improved and how I’ve improved.”

On January 28, Brandon Brewer accompanied Ian MacKillop and Shakeel Phinn to Montreal’s Bell Centre for the Steven Butler-Brandon Cook all-Canadian junior middleweight showdown, a fight of particular significance for Brewer, who competes at 154 pounds. In a seesawing firefight, Cook rallied to bludgeon Butler and score an upset TKO at the end of the seventh round, a result that literally sent the crowd into a riotous frenzy. Cook was struck and dropped by an ice bucket propelled into the ring after a groggy Butler shoved him following the stoppage, and Bell Centre security and police were required to restore order amidst the chaos of fights, overturned tables, and the danger of additional projectiles. Brewer, who was seated near the ring, emerged unscathed. While the behaviour exhibited by certain supporters that night can only be viewed as heinous, the event itself provided compelling evidence of what boxing means to Montreal and how Brewer can fit into the mix. There is more depth in Canadian boxing than ever before, and that reservoir of talent means Brewer can plot his rise to world level through a burgeoning domestic scene.

But first comes his bout against King Davidson on May 27 in Fredericton, a fight Brewer hopes will lead to an active second half of 2017 and get him into the world rankings of at least one sanctioning organization. Once a top-15 rating is secured, Brewer is certain his phone will start ringing with greater frequency, which will lead to the type of financial security necessary to spend more extended stretches in Montreal. Patience could indeed be Brewer’s greatest virtue at this juncture of his career, as he teeters between that limbo of unanimously viable contender and dangerous unknown. But in the meantime, don’t expect Brewer to idle.

May 27th – ‘The Lumberjack is Back’…..and I’ll be choppin down the 21st tree at The AUC. . . . . @maritimekitchenparty doing an insane job with our videos. #lumberjack #ljack #choppintrees #plaidarmy #canada #canadian #ljackpromotions #boxing

In Fredericton, the University of New Brunswick’s Varsity Reds men’s hockey team, who seem to win National Championships at the same rate as the Montreal Canadiens of the 1970s, is the biggest sporting draw in town, but boxing, thanks to Brandon Brewer, is on the rise. However, Brewer is careful to note that the 3,500 fans who have packed into the Aitken Centre for his last two fights are people, not necessarily boxing fans. Prizefighting is still a long way from becoming a self-sustaining industry in New Brunswick, although Brewer is optimistic about the future and a fan base that is clearly willing to rally behind one of their own.

When Brandon Brewer won the 2016 New Brunswick Athlete of the Year award, becoming the first combat sports competitor to do so, he was both shocked and humbled. He got the call about a week before his first ever fight in Fredericton, which meant he wasn’t able to appropriately celebrate. That said, after he’d won his bout, the magnitude of that mainstream recognition set in, confirming that he had indeed come full circle since those days of driving around with a leaking gas tank, desperate to find people willing to take a chance on him. “It was comforting knowing that I’d finally been accepted into this society, into a province that’s basically hockey and baseball.”

The accolades are starting to trickle in for Brewer, but what stands out when speaking to him is the fire that burns deep within him, which only seems to get stoked as he scales new heights. While some would view his being based in Fredericton, New Brunswick, as a form of boxing exile, it’s actually the root of Brewer’s modesty, a large source of inspiration, and a perpetual reminder of everything he’s been through and all that comprises his essence — a reminder of friends and family, of historic evenings in front of an adoring and raucous crowd, of punishing winter nights without heat, of solitary shadow boxing in a parking lot.

“I felt like that was the one edge I had on people: I didn’t live in a big city where I was catered to and handed promotional contracts and touted to be a world champion long before I ever was,” Brewer says. “I was not babied and nothing was handed to me. I worked my ass off. So there is no question of if this works. It will work. It has to work. Because I have no other option.” — Zachary Alapi

Portrait of Brandon Brewer by Mag Hood.