Aug. 31, 1989: Zaragoza vs Duarte

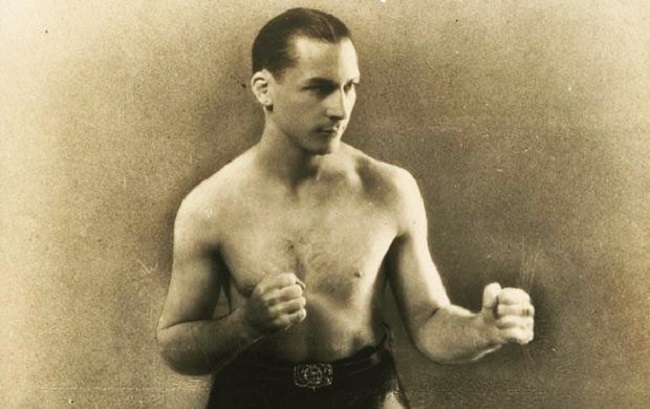

In the 1920s, “Cauliflower Row” became a popular appellation for the fight racket. It was the perfect name, referring to the disfigured ears boxers often wind up with, while also implying that a certain kind of toughness is necessary to make the ring home. But if becoming an elite fighter takes toughness, so does working toward a championship for an entire career, falling short, and then fighting on anyway. On this date back in 1989, it was Daniel Zaragoza who showed grit in asserting himself as world class, while Frankie Duarte just couldn’t seem to win the big prize, despite impressive efforts, not to mention toughness.

Zaragoza donned gloves for the first time at 20-years-old, yet the Mexico City native represented his home nation only two years later in the 1979 Pan Am Games and then the 1980 Olympics, falling just short in both. He became a fine southpaw fighter, turning pro under the tutelage of Ignacio “Nacho” Beristain and winning the Mexican bantamweight title before defending it nine times, which stands as a record. Said Zaragoza’s manager Rafael Mendoza, “Bantamweight is the most popular weight class in Mexican boxing; being the Mexican bantamweight champion is almost as prestigious as being a world bantamweight champion.”

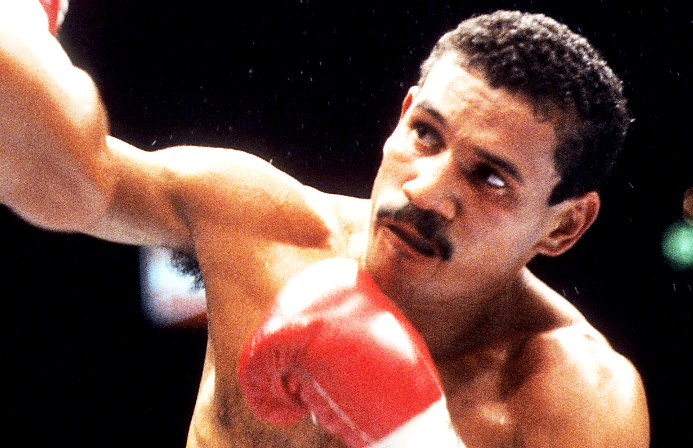

At 27-2, Zaragoza, aka “El Raton,” won the vacant WBC bantamweight belt by sending Fred Jackson packing on a foul, becoming Beristain’s first world champion, before the title was taken from him in his first defense against Miguel Lora. Next was a rough loss to an emerging Jeff Fenech, followed by seven straight wins, then a chance to take on the aged and come-backing Carlos Zarate for the vacant WBC super bantamweight belt. It would be Zaragoza’s first appearance at The Great Western Forum in Inglewood, California, but not his last.

Zaragoza retired Zarate, won the belt, and defended it five times, all on foreign soil: first South Korea, then Italy, then the U.S. twice and South Korea again. If not stylistically, he shared a common trait with stablemate Ricardo Lopez: his demeanor and style weren’t what Mexican fight fans usually crave, despite epitomizing the term “world champion.” Along the way he started what would become a classic trilogy against Paul Banke. But another title defense away from home awaited him, this time against Duarte.

Like Banke, Duarte was a good-looking California kid with an aggressive style and a penchant for trouble, and both fought often at the Olympic Auditorium and The Forum. But Duarte had ten years on Banke; when “The Real” was just trying cocaine for the first time in 1985, Duarte had already kicked a heroin addiction that nearly killed him, and was decidedly on the championship trail.

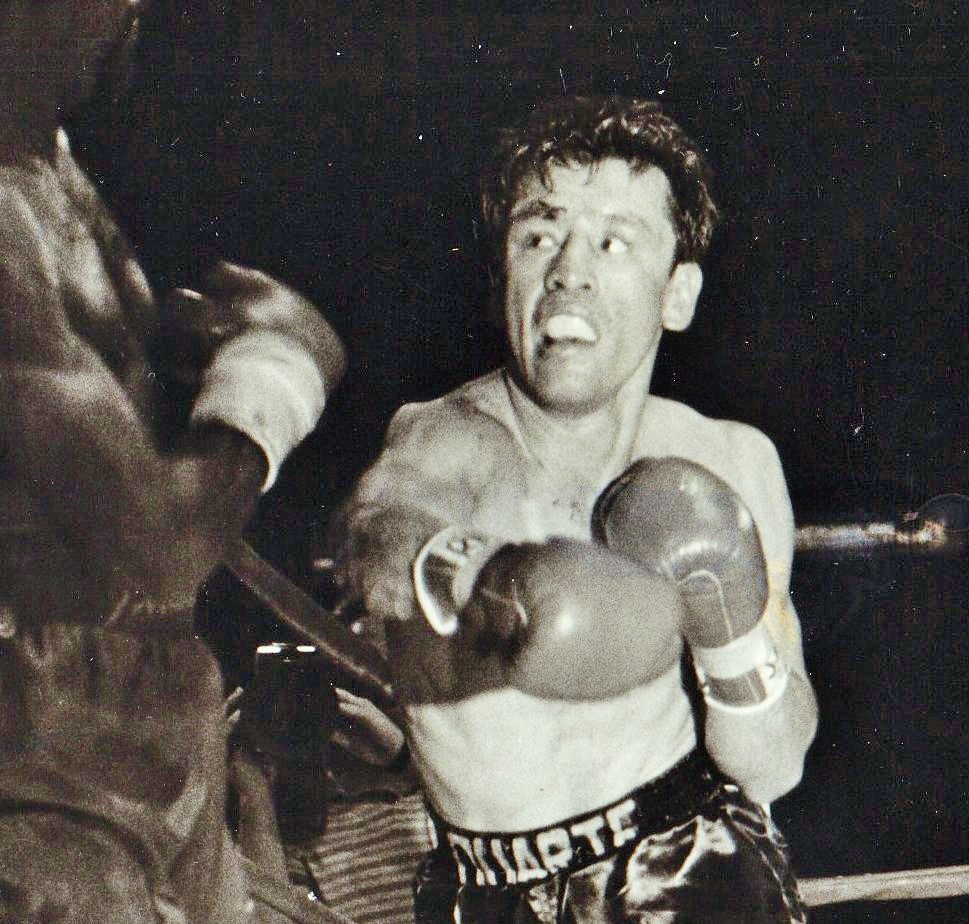

A stoppage defeat to Alberto Davila in a 1977 title eliminator bruised Duarte’s ego, and losses to Rolando Navarrete and Neptali Alamag in 1979 and 1981 respectively, drove the chemical demons Duarte had fought off for years to dig their claws back in. He went off the grid before returning in 1984 with new management from the Los Angeles-based Ten Goose Boxing, going 9-1-1 over the next two-plus years in what would be known locally as the “Miracle at Ten Goose.”

The loss, a split decision to WBA bantamweight titlist Richie Sandoval in a non-title bout, was one year into Duarte’s comeback and was easily overlooked. More disheartening was his subsequent defeat to Bernardo Piñango who was deducted three points, apart from being sent to the canvas in the final round; somehow, he still got a decision. A teary-eyed Duarte, his face mangled from jabs and quick combinations and slashed by headbutts, nervously tapped the podium when asked what he would do next, replying, “I don’t know… I don’t know.”

It took an entertaining, albeit shaky victory, over Davila, one decade after the initial meeting, to temporarily fix matters in Duarte’s head and win him a “Comeback of the Year” award from The Ring magazine. But 18 months later, in early 1989, he was quitting the Ten Goose Gym, broke and bitter that bigger opportunities hadn’t come, intent on retiring at 34 without having won a title. “If someone called and offered me $150,000 to fight, I would have to turn it down because what I stand for is far more important than the money,” declared Duarte. “Others might take the money, take a beating and then have their managers throw in the towel. I won’t do that.”

Yes, he would do that; the $25,000 offer to face Zaragoza for a title belt was too enticing. Duarte had been doing chores around his parents’ house for pocket change, on the verge of having his car repossessed by Ten Goose. Not long before being matched to fight Zaragoza at The Forum, Duarte said, “I would rather retire, but I can’t. I have to fight because I don’t want to lose my house. It’s all I have.”

Just days shy of his 35th birthday, Duarte was unfit to challenge Zaragoza, as evidenced by his struggling against three opponents with a combined record of 52-44-5 following the Davila return. The WBC even chose to give Frankie a boost in their rankings to make a Zaragoza vs Duarte match appear more legitimate.

Zaragoza also did his part to talk up the bout. “A champion should always be prepared for a tough fight,” he remarked to Earl Gustkey of The Los Angeles Times. “I always expect a tough fight. Look at Roberto Duran. Nobody gave him a chance against Iran Barkley, but because he had the heart of a champion, he won.” A fine sentiment, but Duarte was no Duran.

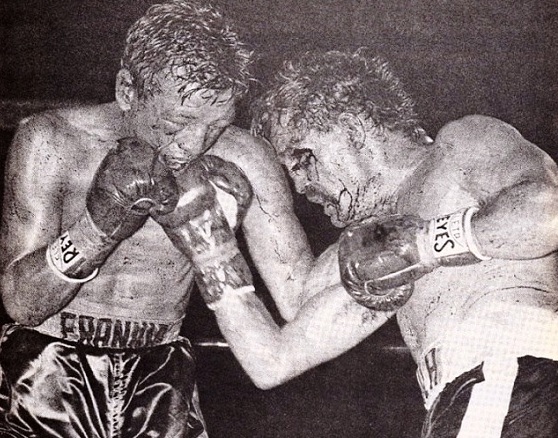

With a style built around disrupting rhythm with odd timing and movement, Zaragoza played his strengths perfectly against a surprisingly sedate “El Guero” in round one. In truth, Duarte’s legs looked used up from the opening bell and by the second the champion was having a difficult time missing with his lead left hand. When the bell to end round three sounded, Duarte walked to his corner with a cut on the bridge of his nose, a reddened right eye and nothing to show for it. And things were about to get worse.

It wasn’t until well into round five that Duarte had any success at all offensively and he was still absorbing long left hands and hard body work. At least it could be said Zaragoza was having to exert himself in front of the 6,300 in attendance. Both men were rocked back on their heels in the sixth, but in the seventh Duarte’s lack of head movement caught up to him. Zaragoza continued thwacking the challenger with jabs and lefts, and as the rounds passed, Duarte’s movement got clumsier and his eyes more swollen.

After round eight Benny Georgino, who had taken over for Joe Goossen as trainer, asked Duarte if he wanted the bout stopped. An inaudible answer led Georgino to tell Duarte he had one more round to get the knockout, but the old man didn’t have it in him as he just took punch after punch. This is what Duarte’s signature late rounds rally, and career, had come to: a valiant effort showcasing his toughness in losing the bigger war.

One more half-round of a beating was plenty for the referee, who stopped it despite Duarte’s protests. Zaragoza had hit Duarte with so many punches that he’d injured both fists, later saying, “I was expecting to knock him out, but after the fourth I had pain in both hands.”

In August of 1975 Duarte had been asked why he was a tenth grade dropout. He replied, “I didn’t mind going to school. I just didn’t like going to classes.” Exactly fourteen years and 35 fights later Duarte was taken back to school and forced into retirement, having never gotten his world title. After the fight a reporter asked Frankie about his future plans and he replied that he would have to look for a job. — Patrick Connor